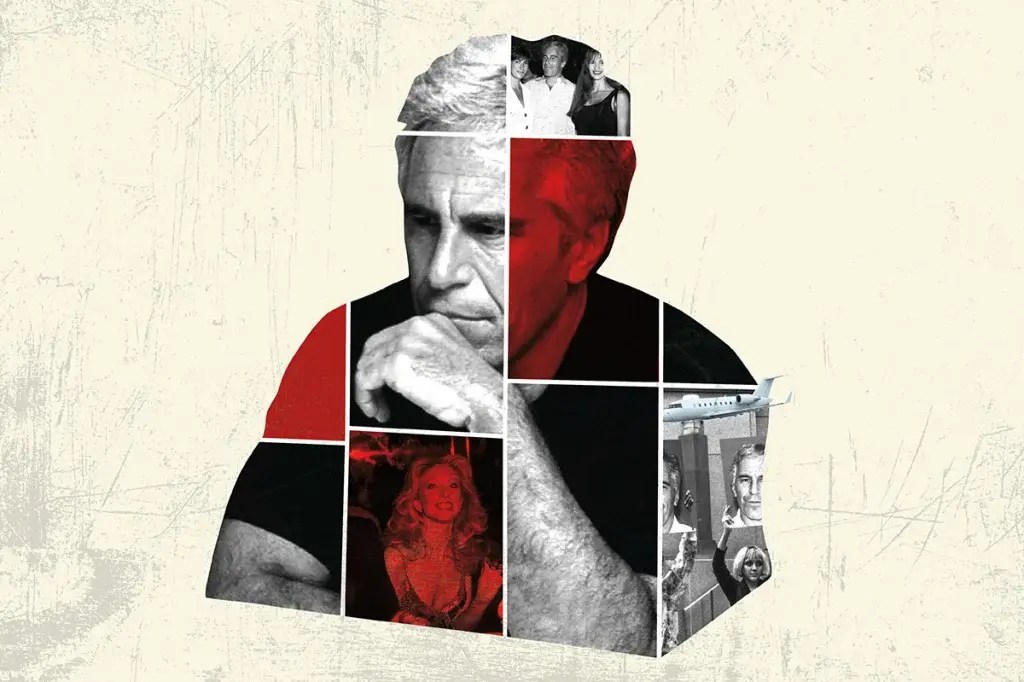

In Joel and Ethan Coen’s 1991 movie Barton Fink, a writer in pursuit of the big story accidentally winds up befriending a serial murderer who lives next door. That dark comedy’s ironic juxtaposition did not escape me in August 2019 when Jeffrey Epstein was found hanged in the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York and the mushrooming scandal involving him threatened to engulf three of the wealthiest men in America, two former presidents of the United States and the second son of the queen of England.

For me, his sad saga began unfolding some thirty-three years earlier when I was still investigating a world-class financial mystery in Europe that began with the hanging of the Italian banker Roberto Calvi, known as “God’s banker,” under Blackfriars Bridge in London on June 18, 1982. It involved an even more sinister financial scandal that threatened to bring down the Vatican Bank and cause what Pope John Paul warned would be “a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions in which the Church will suffer the gravest damage.” Archbishop Paul Marcinkus, the Vatican Bank’s head and a principal player in the scandal, had guided me through some of the inner sanctums of the Vatican, but even with his help, the missing $1.5 billion in funds remained a mystery. I was still trying to unravel the financial threads of the missing money when I encountered Jeffrey Epstein on October 31, 1987.

I had gone that evening with the British businessman Jimmy Goldsmith and his thirty-five-year-old daughter Isabel to a Halloween party at the Upper East Side home in Manhattan of Coco Brown, a movie producer who rarely, if ever, made a movie. Soon after our arrival, a young man in his mid-thirties with a big, toothy smile sauntered up to us, hugged Isabel and introduced himself as Jeffrey Epstein. He was with his brother Mark Epstein. “A surfeit of Epsteins,” remarked Isabel, who knew Jeffrey from London.

The next day, Epstein called me and said there was something he’d like to talk to me about. We met for tea at the Mayfair Hotel on 65th Street the following Thursday. He told me at the outset he had information that I might be interested in for my Wall Street Babylon column in Manhattan Inc. He said he had learned it in the course of his business dealings.

“What is your business?” I asked him.

‘I’m sort of a financial bounty hunter,’ he said, with an I-know-more-than-you grin

“I’m sort of a financial bounty hunter,” he said, with an I-know-more-than-you grin that rarely left his face throughout our tea. He explained that he hunted down hidden money for a fee. He described the convoluted network of concealed funds in Andorra, Fiji, Gibraltar and the Cayman Islands in such vivid detail that it sounded like he might be in the business of hiding as well as finding it. He dropped many legendary names in the realm of money machinations — Adnan Khashoggi, Aristotle Onassis and Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan — but his tales, though intriguing, didn’t quite add up. For one thing, I knew Khashoggi well enough through Jimmy Goldsmith to doubt that he needed help from Epstein in either hiding or finding hiding places for money. I asked him about the only hidden money of interest to me, which was the $1.5 billion from the Vatican Bank that vanished into shell companies in Panama. Epstein knew nothing about those funds. As we finished the tea, I mentioned I was leaving for Spain on Monday.

“How do you go?” he asked.

“Iberia Airlines.” I added that I always flew coach.

“If you like, I can upgrade you to first class. Much better food.”

“How?”

“Drop your ticket off with my doorman tomorrow morning. It won’t cost you a penny.”

Jeffrey lived in a one-bedroom apartment at Solow Tower at 265 East 66th Street. As instructed, I brought my ticket to the doorman on Friday morning, and Friday evening I picked it up with a first-class sticker and a first-class seat assignment. I flew to Malaga, Spain, and back in great style and comfort.

When I mentioned Epstein’s ticket trick to Jimmy Goldsmith, he warned me to be careful with him. It was good advice I did not immediately heed.

In December 1988, I needed to go to Los Angeles to interview associates, and possibly victims, of the so-called Junk Bond King Mike Milken, now involved in a growing scandal. When I told Epstein about it, he not only converted my coach tickets to first class, but he insisted that I stay at his house in Santa Monica. He had rented the two-bedroom house near the pier for his girlfriend Eva Andersson, a former Miss Sweden in her third year of medical school at UCLA. Since I needed to be in Los Angeles for weeks for my interviews, I happily stayed at Eva’s house. She couldn’t have been a better host.

Epstein had another surprise for me in LA. It came in the form of a call from the actress Morgan Fairchild. At his behest, she met me for lunch at the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel. She was preparing for her role in the upcoming Murphy Brown TV series, and Epstein had told her I could tell her all she needed to know about investigative journalism. It was a subject that typically made people’s eyes glaze over, but Fairchild seemed keenly interested. I dined with her many times in LA.

Back in New York, Epstein introduced me to a diverse group of his acquaintances. We had lunch with Leslie Orgel, a Salk Institute theoretical chemist who, over lunch at the Italian Pavilion, said that human life might have been seeded on earth by a higher intelligence in the universe, a theory that greatly interested Epstein; Vera Wang, a former Vogue editor, who had just opened a bridal-dress store on Madison Avenue; Evangeline Carey, the wife of former governor Hugh Carey, who shared an office with Epstein at Villard House; and Stuart Pivar, a Brooklyn-born scientist who made a fortune in plastic containers and helped endow the New York Academy of Art. Epstein also took me to several events at the Academy of Art, including his former girlfriend Paula Fisher’s wedding celebration (which ended in a food fight between Pivar and Barbara Guggenheim).

It was all dazzling fun, but in late 1988 a dark cloud began to overshadow the festivities

It was all dazzling fun, but in late 1988 a dark cloud began to overshadow the festivities. It began when I tried to board an ANA flight to Jakarta that Epstein had upgraded to first class. The ANA representative told me it could not be a first-class ticket, which cost $6,000, because I had only paid $655. When I pointed to the first-class sticker, she said anyone could steal one and paste it in. I was unceremoniously moved to coach.

I later asked one of his girlfriends about the upgrade. She told me it only works about one in three times, and that Epstein would send her to the airline counter to check to spare himself the potential embarrassment. She explained he had obtained the stickers from a friend and, after pasting them on, entered the airline’s computer to make the seat assignments. I suspected Epstein had obtained the first-class stickers from Pan Am Airlines, of which he was working with Steven Hoffenberg on a failed attempt to get control. I had met Hoffenberg with Epstein at the Regency Deli in New York. Epstein told me he owned a bill-collection agency. Hoffenberg was a tall man with dark sinister eyes who looked the part of a tough repo collector.

The cloud darkened further when I got a frantic call from Dick Snyder, the CEO of Simon & Schuster, the publisher of my book Deception: The Invisible War Between the KGB and the CIA. Snyder had met Epstein at a dinner at my house. He told me he had given Epstein $70,000 to invest in a deal to take over the chemical company Pennwalt. He told me that after sending the money, he had not received the necessary papers and that Epstein was not returning his calls. He called one of the principals in the deal, who said he had never heard of Snyder. I told him I would look into it.

I was puzzled as to how Epstein, who only a few years earlier had bounced checks, had come into this windfall

Epstein was in Palm Beach at the time, but he had given me a computer program called Carbon Copy so I could get real-time quotes on the stocks I was interested in. It was another way of showing off his technological prowess. The program allowed me to remotely access his computer via my telephone modem. I decided to use it to find out what was going on with my publisher’s investment in Pennwalt. Remotely, I clicked on “home” on Epstein’s computer and went to the archive, where I found a file of recent transactions. In it were dozens of letters from people demanding the return of their investments, including Vera Wang’s father, C.C. Wang, the owner of a pharmaceutical company. Another was from a financier involved in the takeover deal of Pennwalt who reported that a check from Epstein for $83,000 had bounced a second time. The sums were considerable, but from the one-way correspondence, I could not determine if they were repaid. One set of transactions involved Steven Hoffenberg, the person who may have indirectly provided my first-class stickers. Rather than demanding repayment, he wanted to transfer large sums to Epstein from Associated Life and United Fire, two small insurance companies that Hoffenberg controlled. As I read through this material, I found nothing about Snyder’s money, but I grew increasingly queasy about Epstein.

***

In early 1989, I wrote my Wall Street Babylon column about a small-time grifter trying to pass as a big-time financier. Although this character was modeled on Epstein, I didn’t identify him by name. The point of the column was that the takeover game had become so lucrative that even operators without money — who had their power breakfasts in the Regency Deli instead of the Regency Hotel — could play in it. All that was needed was enough charm to convince investors they too could score like the big corporate raiders. It was titled “The Win-Win Game.” After it was published, Epstein stopped speaking to me.

Epstein, meanwhile, had reportedly scored well in the win-win game. I heard of his success from Eva, who had married Glenn Dubin, a financier with whom I invested. Epstein had moved from his one-bedroom apartment in the Solow Tower, first to a townhouse that had belonged to the Iranian government before it had been seized by the US government in 1977, and then to a mansion on 71st Street. That mansion had previously belonged to Les Wexner, the billionaire chairman of L Brands, which owned Victoria’s Secret, The Limited and other retail chains, and who Epstein bragged he was advising. According to other mutual friends, I learned that he had acquired a large ranch in New Mexico, a mansion in Paris with a stuffed baby elephant in the living room, and a private airliner. I was puzzled as to how Epstein, who only a few years earlier had bounced checks, had come into this windfall. Were his apparent newfound riches the product of his own financial skills? Or, in light of his reported association with politicians, power brokers and financiers, was he a larger-than-life version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby?

These doubts escalated when I had lunch in 1994 with Alfred Taubman, who, among other things, owned Sotheby’s. Taubman, who I had met at Jimmy Goldsmith’s home in Mexico in 1989, told me over a long lunch at San Pietro on 54th Street of his discovery that Epstein had extorted a kickback of $65,000 from the commission due to Sotheby’s real estate brokerage arm from Wexner’s original purchase of the mansion on 71st Street. According to Taubman, Epstein, to whom Wexner had given a power of attorney, threatened to block the deal unless he got his kickback, which he called a “finder’s fee.” Even though it was possibly illegal to pay a share of the commission to someone who was not a registered real estate broker, Sotheby’s paid him. When he found out, Taubman demanded Epstein repay Sotheby’s, but Epstein coldly refused. Taubman went directly to Wexner, with whom he had served on several boards. But Wexner laughed off the kickback, saying Epstein had extracted it simply to demonstrate that he could reduce Sotheby’s commission, and, just that week, he had given it back to Wexner as a “present.”

So I was not surprised in 1996 when the corporate detective Jules Kroll told me he was conducting a discreet investigation into Epstein’s background. I owed Kroll a favor since he had helped me in my Vatican Bank investigation by providing me a videotape of a reconstruction of the hanging of Roberto Calvi that proved that “God’s banker,” rather than committing suicide, had been murdered. Kroll sent one of his top investigators, Thomas Helsby, to interview me about Epstein. Over our lunch at Petaluma, Helsby told me that a board member of Wexner’s company, concerned about Epstein’s influence over Wexner, had personally hired the Kroll agency to find out about Epstein’s past. Its investigators had already determined that Epstein had not been truthful in his claims that he had academic credentials. In fact, he had dropped out of college, worked as a roofer in Brooklyn, and faked his résumé to get a teaching job at Dalton, the private school on New York’s Upper East Side. This did not come as a total shock. Even though Epstein told me he had a degree in nuclear science, I had always assumed that, like Jay Gatsby, he had invented his credentials as well as himself.

The real shock came ten years later when I read that Epstein had been arrested in Palm Beach for soliciting underage women to perform sexual acts. I knew he liked the company of highly attractive women but not underage ones. The women he had introduced me to all had substantial careers: doctors, actresses, art dealers, theater producers, academics, money managers and filmmakers. It didn’t occur to me that he would consider having sex with underage girls. Such ugly perversity was not only criminal, but it made him vulnerable to blackmail. Evidently, he had fallen prey to the “master of the universe” complex in thinking he was immune from federal law and the rules of civil decency. In true master of the universe style, he made a deal with the Department of Justice, pleaded guilty to two charges of soliciting and underage prostitutes, and went to prison in Florida for thirteen months.

***

After a hiatus of some twenty-four years, I heard from Epstein in April 2013. He said he had read an article I’d written in the New York Review of Books on Nabokov, and he would love to discuss it with me. He invited me for tea the next afternoon at his home.

I went because I wanted to see this mansion he had acquired from Wexner. On the outside of his house on East 71st Street, just off Fifth Avenue, was a plaque with the initials “JE.” A tall, striking woman in her late twenties answered the door with a friendly smile. She introduced herself as Jennifer and showed me to the anteroom. The walls contained photographs of rich and powerful men posed with Epstein. There were three photos of him with Bill Clinton. (As I would later learn, the visitor logs at the White House showed that Epstein visited Clinton there no fewer than seventeen times.) When Jennifer reappeared, she asked if I would like an omelet or anything else to eat and led me to a long rectangular table in the dining room.

“Just tea,” I replied.

A few minutes later, Epstein came in accompanied by Svetlana, another of Jeffrey’s assistants. She was almost as tall as Jennifer. Then a third assistant came in the room, named Leslie, who served us tea and left with Jennifer.

Epstein, wearing a tracksuit, sat at the head of the table. Except for his gray hair, he looked very much the same as the last time I’d seen him, in 1989. His glistening know-it-all smile had not changed. He began the conversation by saying that Nabokov was his favorite writer and he kept a copy of Lolita next to his bed and on his plane. He wanted to know what the author was like. The last time I had spoken to Nabokov and his wife, Vera, had been more than a half century before, and my memory of him was dim, but I recounted a few vivid impressions. I then asked Epstein what he was working on.

He began the conversation by saying that Nabokov was his favorite writer and he kept a copy of Lolita next to his bed and on his plane

He told me his main interest was cutting-edge artificial intelligence. He was funding a group in Hong Kong to produce “the world’s smartest robot,” which would have “more empathy than a woman.” He said one problem his robot team had was simulating the feel of human skin. As he discussed the progress on the prototype robot, I couldn’t help thinking of George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion. In it, a phonetics professor, Henry Higgins, attempts to implant his intelligence in a young flower girl and winds up enthralled with his own creation. I asked, “What would the robot be used for?”

“The elderly,” he answered. His theory was that advances in medicine and biotechnology would result in an increasingly large population of centenarians, many of whom would need twenty-four-hour assistance. Empathetic robots would provide it.

I changed the subject. “How do you make money these days?”

“I manage money for a few select clients,” he replied.

I knew that his guilty plea to felony charges in Florida in 2008, including soliciting sex from a minor, would have made it difficult, if not impossible, to get a license to manage other people’s money in the US. So how was he making his money? “Do you have an offshore hedge fund?” I asked.

His smile broadened. “Hedge funds are a thing of the past. But there are wealthy individuals in various parts of the world who need help protecting their assets. I help them.”

In the anteroom, along with the Clinton photos were photos of Epstein with Saudi prince Mohammed bin Salman and Emirati prince Mohammed bin Zayed, some in beachwear and with snorkel gear. I asked, “Are these clients in the Middle East?”

He answered that some were and that he was planning to buy a house in Riyadh since that was becoming the new center of international finance.

“What about Russia? Any clients there?” I asked.

He shrugged and said he often flew to Moscow to see Vladimir Putin.

I found this hard to swallow. He was, after all, a fabulist, as I’d learned from the Kroll report. Nor did it make any sense to me that powerful financiers would trust someone like Epstein to secure or hide their money. After all, they knew he had made a deal with the Department of Justice to avoid federal charges. How could they be sure he wouldn’t make another deal to reveal their secret funds?

When I asked him further about the service he performed for these men, he called it jokingly a “reverse Ponzi scheme,” explaining that instead of making it appear there was money when there was none, which is the essence of a real Ponzi scheme, he made it appear there was no money when actually there was money.

I understood that a wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing strategy might be useful in warfare, but why would a wealthy person want to seem poorer than he was? Who would pay him for such a service?

Before I had the chance to ask him more about his business, Leslie opened the door a crack and announced, ‘Leon is here’

He said there was no shortage of rich spouses, without a pre-nuptial agreement, seeking a divorce. By reducing their apparent assets, he would save them a small fortune.

I was unsure whether or not he was speaking hypothetically. But if he found potential clients for his reverse Ponzi strategy among people interested in minimizing alimony, he could likely also find them among individuals wanting to minimize their tax liability and the exposure of ill-gotten gains. Before I had the chance to ask him more about his business, Leslie opened the door a crack and announced, “Leon is here.”

Svetlana rose to her feet. I assumed it was my signal to leave, but Epstein seemed in no rush to end our chat. He went on for another fifteen minutes discussing his curious enterprise.

Then, walking me out, he introduced me to a man patiently waiting in the anteroom with Jennifer. It was Leon Black, who I had met once before during my investigation of the junk bond world, where he worked for Mike Milken. He was now head of Apollo Global Management, a private equity fund with over $300 billion in assets, and had a reported personal net worth of $10 billion. He was also one of the most important collectors of modern art in the world. I wondered what was he doing patiently waiting in the anteroom of Epstein’s home. His very presence there made me realize that I had underestimated Epstein’s continued connections with the rich and powerful.

I saw Epstein only occasionally over the next six years. Almost all of our meetings were in that same room in his house for afternoon tea. New pictures were on his walls that showed him with unlikely acquaintances. Indeed, at one point, he talked about putting together a dinner at his home with the linguist Noam Chomsky, the movie director Woody Allen, former president Bill Clinton, and the living God, the Dalai Lama. If it occurred, I was not invited.

Only once did we go out for lunch. In May 2014, we went on a walk into Central Park to a hot dog stand with two of his friends. He called its fare “the best hot dog outside of Coney Island” while passing one to each of us.

Four of his female assistants, including Jennifer and Svetlana, accompanied us. They walked at a discreet distance, two on either side of our group, keeping pace in a way that caused Epstein to jokingly call them “my Russian wolfhounds.” They were more functional than that, since they carried, in case Epstein needed them, Fiji water, cash and cell phones.

I got the opportunity to find out more about Epstein’s female staff through a chance meeting. A week after our walk in Central Park, I ran into Jennifer in Maison Kayser, a café on Third Avenue and 74th Street. She said she was buying croissants for a trip she was taking to Little St. James, Epstein’s private island in the Caribbean, that afternoon. Over coffee, I asked how she had met him.

She had come to New York from Minnesota to be a model and wound up in a difficult relationship with a man. Enter Epstein, who rescued her from it and gave her a job as an assistant. He also gave her free use of an apartment on East 66th (near where he had lived in 1989). When she told him that she dreamed of being a chef, he paid for her to take courses at the Culinary Institute of America, arranged a part-time internship for her at a steak house and found her a full-time position in the food industry.

I next asked her about Svetlana, the assistant who had sat across from me at my first tea with Epstein. She told me Svetlana was now studying dentistry at NYU at Epstein’s expense. At that point, I recalled that Eva Andersson, his former girlfriend, had, with Epstein’s help, become a doctor. She became the chief doctor for NBC News and founded with her husband the Dubin Breast Cancer Center at Mount Sinai Hospital. A chef, a dentist, a doctor, an empathetic robot? I wondered after speaking to Jennifer how far Epstein’s Pygmalion ambitions went.

Epstein befriended Bannon after Trump fired him in 2017

I spoke to Epstein on February 25, 2019, just after Robert Kraft, the wealthy owner of the New England Patriots, was charged with two counts of soliciting sex in a massage parlor in Jupiter, Florida. The police claimed his arrest was part of an investigation into suspected human trafficking. Epstein had pleaded guilty to two counts of soliciting sex in Florida and said the difference was that Kraft went to a massage parlor while Epstein had hired women from massage parlors to come to his house. Both cases involved long-term police surveillance. Epstein pointed out, “In my case, the police had gone through my garbage for months and had my house under surveillance according to the report. No one had asked the question how they could allow young women to go in and out, and not protect them and question them if they truly believed they were underage.” His outrage, if I understood him correctly, was that if the local police had acted sooner and prevented underage girls from coming to his house, he would have been spared the need to make the deal with the federal government.

After the Miami Herald published an exposé of his exploitation of women in November 2018, Epstein sought help, as I learned from one of his close friends, Steve Bannon, Trump’s former strategic advisor. Epstein befriended Bannon after Trump fired him in 2017 and even planned a trip with him on his plane to the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Now he sought Bannon’s help restoring his public image. Bannon suggested Epstein should go public by giving an exclusive interview on CBS’s 60 Minutes or another high-profile TV show. Bannon then became his media coach and schooled him on how to take control of a television interview. To this end, in March 2019, Bannon prepared him through a sham 60 Minutes interview in the living room of Epstein’s mansion with a TV camera crew and indoor lighting. Playing the role of a 60 Minutes interviewer, Bannon fired questions at Epstein about the source of his money, his guilty plea and his relations with women. Although Epstein thought he did well in this trial run, according to a person who attended this mock interview, he decided against having Bannon try to arrange a real 60 Minutes interview.

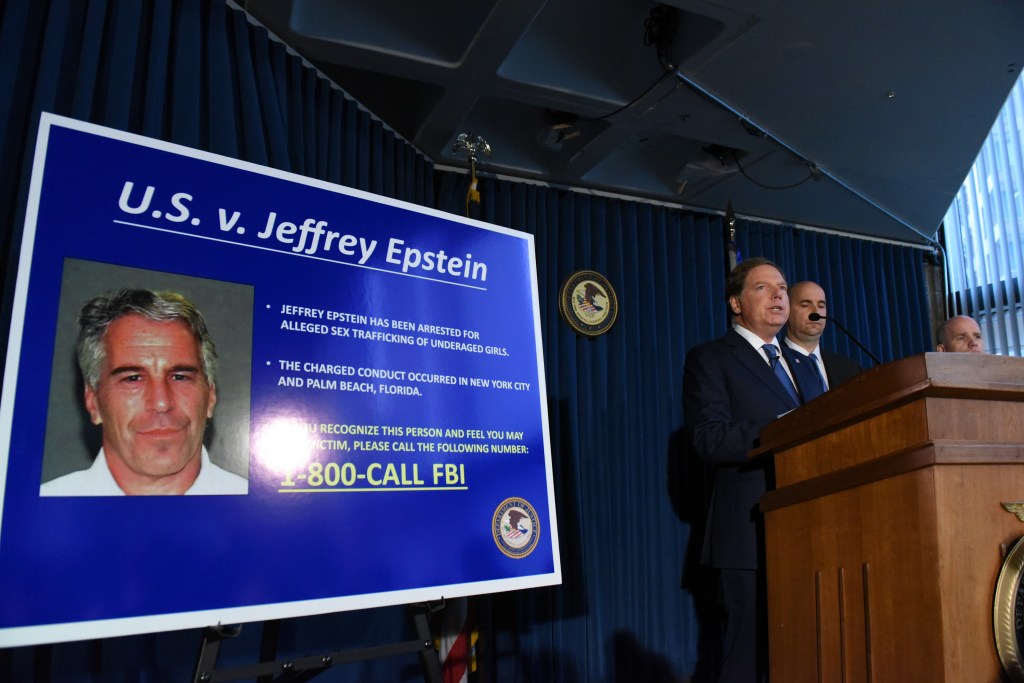

The ax finally came down on Epstein on July 6, 2019. After flying back from Paris, he was arrested at Teterboro Airport by an FBI SWAT team. He was hauled off to the Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC), the federal detention center in Manhattan. The indictment charged that Epstein had recruited women under the legal age for sex between 2002 and 2005 and engaged in sex trafficking. He would not be a free man ever again.

Martin Weinberg and other of Epstein’s defense lawyers expressed to me doubts about this finding

Epstein was found dead on the floor of a jail cell at the MCC on 6:30 a.m. on August 11, 2019. How did he die in a locked cell just fifteen feet away from two guards? Barbara Sampson, the chief medical examiner in New York City, determined the cause of death was suicide by hanging — a finding she said was based on a “careful review of all investigative information.” The presumed motive was that he could not face remaining in prison.

Martin Weinberg and other Epstein defense lawyers expressed to me doubts about this finding. Unlike the coroner, they had direct knowledge of Epstein’s state of mind less than eight hours prior to his death, since they had met with him in the MCC. Telling Epstein that they were about to file an appeal for bail with additional security measures designed to meet the judge’s stated concerns, in addition, Weinberg told him there was a high-level Department of Justice witness who had agreed to swear that the prosecutors in Florida had illicitly transferred material about Epstein to prosecutors in New York, an error that provided grounds for Epstein’s indictment to be quashed. Since when they left Epstein had seemed buoyed over these developments, and expressed hope about being released on bail, his lawyers could not see any clear motive for him to kill himself a few hours later.

In any case, his sudden demise added to the mystery of the source of Epstein’s wealth. According to the court filings released after his death, he had $577,672,654 in cash, bank deposits and property. This meant in the thirty years since I first met him, he had gone from being a small-time grifter, who faked airplane upgrades and bounced checks, to a tycoon who had amassed over a half-billion-dollar fortune, even after he had paid out tens of millions of dollars to settle lawsuits by his “Jane Doe” victims, as was required by his plea agreement and vast legal fees. He had also given over $100 million for scientific research at Harvard, MIT and other universities. He told me in 2013 that he was working with Bill Gates to create a multi-trillion-dollar philanthropic fund, a claim that I did not believe. Yet the New York Times, partly confirmed, reported after his death that Epstein told Gates he had “access to trillions of dollars of his clients’ money that he could put in the proposed charitable fund.”

But how could he have clients since he could not legally manage other people’s money after his felony conviction? He also had no known business enterprises other than shell companies registered in the Virgin Islands.

The first postmortem question that arose involved the origin of Epstein’s money. How did he go from bouncing checks in the late 1980s to having private planes in the early 1990s? The person in a position to answer was Steven Hoffenberg. When Epstein introduced me to Hoffenberg in 1988, he had an armed bodyguard and struck me as an odd business associate of Epstein’s. Seven years later, I discovered that Hoffenberg was a major-league swindler. In 1994, he was charged with running a massive Ponzi scheme during the time he was involved with Epstein, in which some $475 million was stolen from clients and banks. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to twenty years in prison. But a large part of the missing funds was not recovered.

How did he go from bouncing checks in the late 1980s to having private planes in the early 1990s?

When Hoffenberg got out of prison in 2013, he went, uninvited, to Epstein’s home to demand money that he claimed Epstein owed him. According to Epstein’s version of the confrontation, Epstein told Hoffenberg that he was crazy and threw him out. But Hoffenberg told a different story. In a recorded interview in September 2019, Hoffenberg said that Douglas Leese, a London financier, had introduced him to Epstein in 1987 as someone who could help him in his criminal enterprise. Leese, who had employed Epstein to do money laundering for his clients, recommended Epstein, according to Hoffenberg, because Epstein had a “criminal mindset.” So Hoffenberg hired him to help in the Ponzi scheme for part of the loot. If true, it could go some way to explaining how Epstein got his windfall. But the problem with Hoffenberg’s story was that Epstein was never implicated by either the state or federal prosecutors of the Ponzi scheme, not even after Hoffenberg and his associates at Towers Financial cooperated with the investigations. Why didn’t Hoffenberg name Epstein as a participant in the swindle? Was Hoffenberg counting on Epstein to hide part of his money since he had often bragged about his ability to hide money? What Hoffenberg claimed after getting out of prison, though Epstein denied it, was that some of Epstein’s money belonged to him.

Wherever Epstein’s original windfall came from, it was established after his death that at least two billionaires paid him hundreds of millions of dollars long after Hoffenberg was arrested. Presumably, he provided for them a benefit. And from everything he and others told me, it was financial in nature.

One of them was Les Wexner. Born in 1937 in Dayton, Ohio, to parents of Russian Jewish origins, he made a multibillion-dollar fortune off of his retail chains well before he befriended Epstein in the late 1980. My friend Alfred Taubman, who was Wexner’s close friend and mentor, told me that Wexner granted Epstein power of attorney over his personal finances, made him a trustee on the board of the Wexner Foundation, and permitted him to choose models for Victoria’s Secret fashion shows. By 1994, Epstein had so involved himself in Wexner’s finances that Taubman pointedly asked Wexner about allowing Epstein such latitude. Wexner replied, “If you knew how much money he has made me, you wouldn’t ask.” As far as Wexner was concerned, his relationship with Epstein was all about money, but in July 2008, he discovered that Epstein had misappropriated millions off of him by taking excessive fees and other means. He revealed after Epstein’s death that Epstein repaid his foundation $46 million but claimed that was only part of the missing funds. It becomes a criminal matter when someone with a power of attorney misappropriates funds. The fact that Wexner never pursued the matter by informing the authorities raises a question about the nature of the services that Epstein was providing.

Leon Black was the second multibillionaire who paid large sums to Epstein for his services. Born in July 1951 in New York City, Black was the son of Eli Black, who headed United Brands Company. After becoming a top deputy to Michael Milken at Drexel Burnham Lambert, Leon Black cofounded Apollo Global Management, which became one of the largest private equity firms in America. He became friends with Epstein in the mid-1990s at a time when Epstein, nearing the peak of his political influence, was a frequent visitor at the Clinton White House. Soon afterward, they entered into a business relationship that lasted until 2017, and Epstein was made a trustee of the Debra and Leon Black Family Foundation.

According to a close associate of Jeffrey Epstein, Black broke off both the personal and the business relationship in 2018. After Epstein’s death, Black said in a press release that he had paid Epstein for his advice on “tax strategy, estate planning and philanthropy.” Although tax avoidance schemes could fall in a gray area, it was not unusual for wealthy men to pay brokers a fee of 5 to 10 percent of the money saved if they found a loophole in the tax code. According to Dechert LLP, a law firm hired at Black’s request by Apollo’s board, Black paid Epstein around $158 million from 2012 through 2017 for financial services, suggesting that Epstein had saved him at least $1.3 billion.

But the means Epstein used became murkier when the New York Times revealed that, according to documents it reviewed, Black had paid Epstein at least $50 million in suspicious wire transfers that drew scrutiny of the Deutsche Bank, which handled them. And Black transferred money to other entities controlled by Epstein, supposedly as an investment. According to a lawsuit brought against Epstein’s estate by the attorney general of the US Virgin Islands, Black, along with his personal holding companies, invested possibly as much as $154 million in the Southern Trust Company, a corporation that Epstein created in the Virgin Islands in 2013 to do DNA data research, but it produced no profits. Black, as was his right, did not explain the rationale for these investments.

I discussed Epstein’s activities in 2020 with a financier who had known Epstein since the late 1990s. Like Wexner and Black, he was also a philanthropist and art collector. “Why did anyone give Epstein money?” I asked.

The financier told me about a proposition Epstein had once made him. Epstein told him that he could save him over $40 million in US taxes if he gave him $100 million to put through a maze of offshore nonprofit companies that he controlled, and the funds would wind up, free of taxes, in the financier’s foundation. When the financier told Epstein that the scheme could amount to fraudulent tax evasion, Epstein replied that it was highly unlikely the IRS would unravel it, and if it did, he could protect the financier from any criminal exposure if he gave him total power of attorney over the funds, as if this ploy would provide an alibi for him to the IRS. Shaken by the criminal nature of the offer, the financier turned down Epstein’s proposition. It is possible that other, less prudent investors entered into Epstein’s reverse Ponzi scheme.

This excerpt is adapted from Assume Nothing: Encounters with Assassins, Spies, Presidents, and Would Be Masters of the Universe, published by Encounter.