The reaction of markets to the US trade deal with Japan shows yet again that if you presage bad news with even worse news you can make people pathetically grateful at the outcome. Shares in Toyota surged by 14 percent at the news. Yet why, when the deal will see imports of Japanese cars to the US slapped with tariffs of 15 percent? Because back on “Liberation Day” in April, Donald Trump announced that Japanese imports would be subject to 24 percent tariffs.

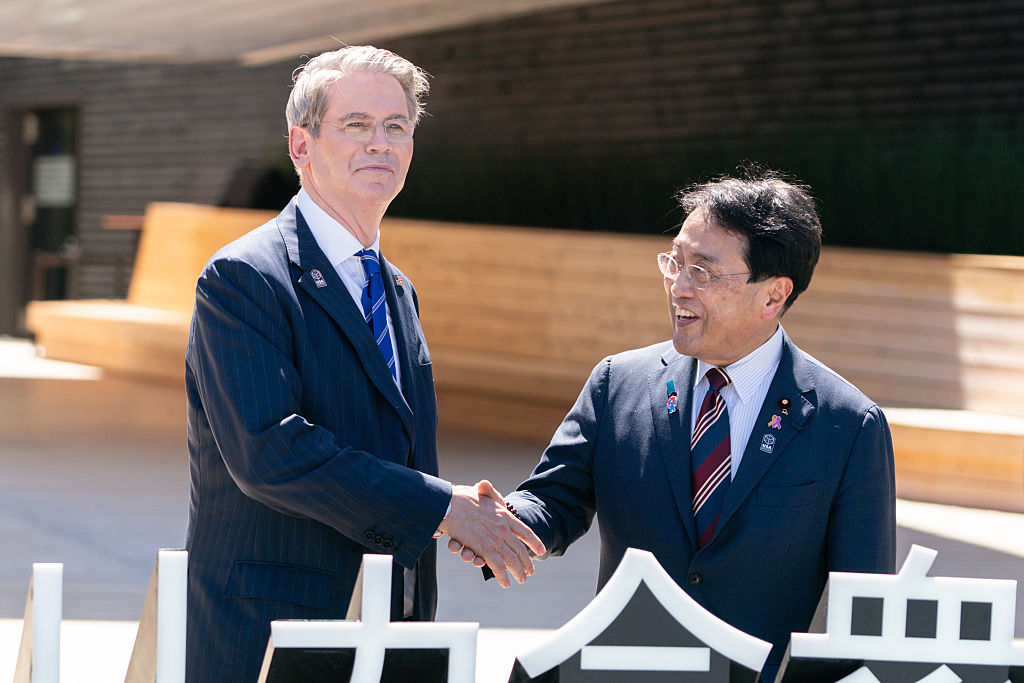

Reactions to Trump’s reset in trade relations with the rest of the world have undergone wild swings in recent months. First, markets plunged. Then, as the President pulled back, reduced all the tariffs announced on Liberation Day to 10 percent and started to negotiate, there was a rebound on what became known as the TACO – “Trump Always Chickens Out” – trade. But the deal with Japan shows that Trump hasn’t really chickened out at all. The end result – if indeed this does settle trade relations with Japan – is what you would expect in any negotiation: one side puts down an opening demand which then gets watered down as the haggling progresses until both sides reach a position on which they can agree. The outcome is in fact balanced: imports of Japanese cars to the US will now attract the same tariff – 15 percent – as imports of American cars to Japan. The Japanese will also remove quotas.

The Japanese deal is a model for what we can now expect with other countries. In the case of countries which are prepared to negotiate – which will be most of them – we will end up with US import tariffs which are markedly lower than those announced on Liberation Day but which are nevertheless higher than those that existed before 2 April. One or two, such as Russia, which didn’t feature on Liberation Day but which is now being threatened with punitive tariffs unless it agrees to end the Ukraine war, might turn out to be special cases. But for the most part, global trade will be able to continue, just on a more level playing field, with tariffs on US imports closer to those which tend to be levied on goods and services going in the opposite direction.

That could be presented as a negotiating triumph for Trump – he looks like he’s getting what he set out to achieve which is a more equal tariff regime. The whole business has exposed what few appreciated beforehand: that the US has long tended to more welcoming to other countries’ imports than other countries have been to imports from the US. Prior to Liberation Day, the World Trade Organization gave an average tariff rate for the US of 3.4 percent, lower than virtually any other major country in the world. For Japan it was 4.2 percent, the EU 5.2 percent, the UK 3.9 percent and China 7.5 percent.

But will it really benefit the US to have a more equal tariff regime? While it might seem tempting to think that it is unfair for country B to charge higher tariffs on imports from country A than country A charges on imports from country B, that does not necessarily mean that country B is the winner. Country A’s exporters may feel cheated, but its consumers will feel very different: low import tariffs charged by their government is giving them greater choice and lower prices. Moreover, even exporters tend to consume imports, too. Take a car company. While it might want to export some of its finished product, it is almost certain that there is a significant number of imported parts and raw materials in its supply chain. If, say, General Motors is selling a car to a US consumer it is aided by low import tariffs imposed by the US while export tariffs are an irrelevance.

Fact is that countries which have low import tariffs have tended to be among the most economically successful in recent decades. Bottom of the WTO’s list for import tariffs is Singapore, which has grown from a third world country to one of the world’s richest nations in just two generations. I can’t see the Singaporean government announcing its own “Liberation Day” and jacking up tariffs any time soon. China, on the other hand, has grown wealthy in spite of levying relatively high tariffs. And it is China which tends to grab the majority of the attention on trade issues. Nevertheless, it is also possible to argue that China’s economic growth has been skewed badly by its trade policy, and it would be a lot healthier now – and its consumers a lot happier – had it lowered its tariffs.

Either way, as more trade deals follow that of Japan and the Philippines announced today, Trump will be able to claim a negotiating success. But that doesn’t mean Americans will be better off for it.

Leave a Reply