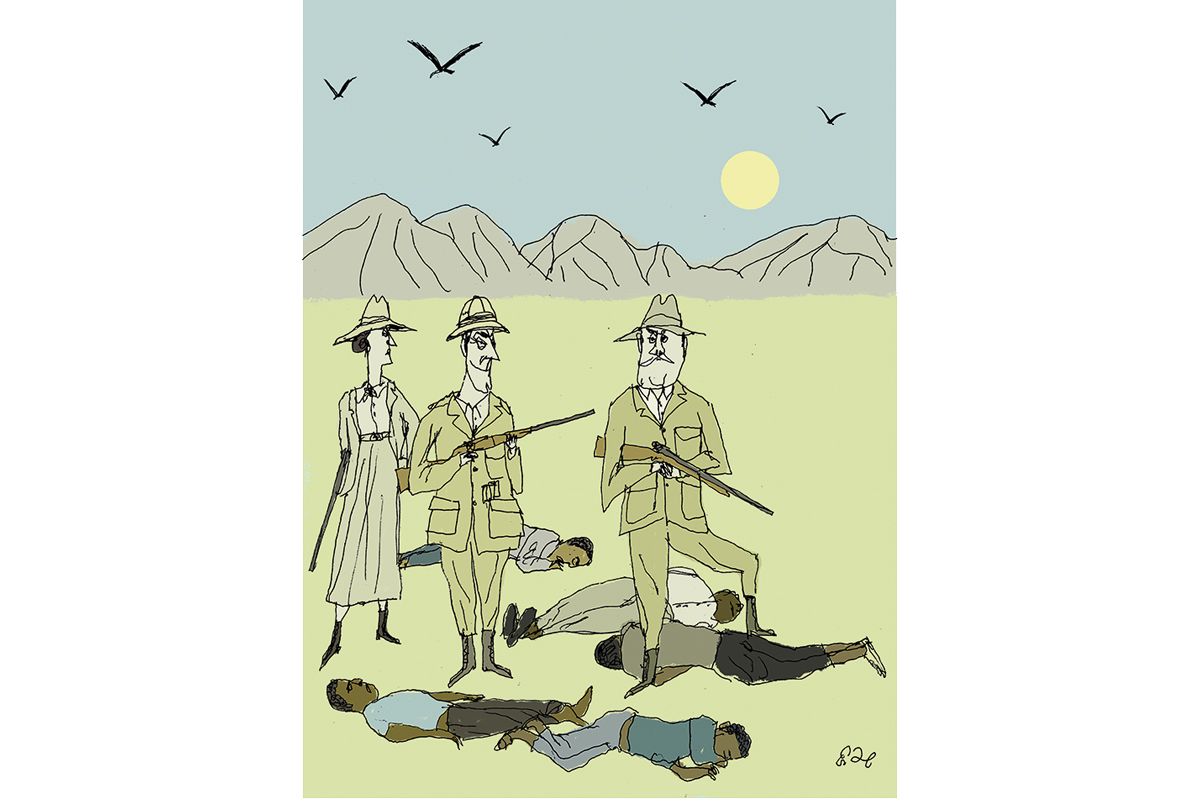

I used to believe that there were only two options for leadership change in the Middle East: the coup or the coffin. But now there’s another thing for embattled authoritarians to worry about. It’s not the Republican Guard, CIA, MI6 or Mossad, Delta Force or the SAS — it’s COVID-19. And while the virus may well end up fundamentally changing many of our own political expectations, not least about China (Huawei anyone?), and the resilience of our own societies, it may have an even bigger impact on the fragile political ecosystem of the Middle East and North Africa.

And that’s because it is there that a superannuated old order has most persistently refused to die. Revolutions have been dead ends, reform an illusion. No new political dispensation has been carried to term for 70 years. The body politic in many Arab countries — and Iran — was already suffering from serious underlying health conditions. And now this.

Iran has had the worst of it so far. After a long period of denial, the health minister announced on March 19 that people were dying at a rate of one every 10 minutes — and this was accelerating. As I write, the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre reports 50,000 confirmed cases and over 3,000 deaths, the fifth highest mortality rate in the world. And that’s just the official figures, which many Iranian doctors in private claim are a vast underestimate. Several ministers, senior politicians and others close to the Supreme Leader have succumbed. The heart of the epidemic seems to have been the shrine and pilgrimage city of Qom, which is central to Iran’s production of clerical knowledge and power, and therefore to the regime’s legitimacy. Around 20 million Iranians and 2.5 million foreigners visit every year, with many of the latter, who include several thousand Chinese, studying in densely packed seminaries.

The regime has long seen China as a counterbalance to western, particularly US, pressure. It has ignored Chinese persecution of Uighur Muslims and has gone to great lengths instead to develop air and rail connections between the two countries. Unusually, the IRGC-controlled Mahan Air kept flying into China well after Beijing had acknowledged the seriousness of the outbreak in Wuhan and other transport links were being closed down. The flights may have brought back not just contraband but also the virus, which 16 other countries claim Iran then re-exported to them.

The regime denied that it had taken hold until too late. It encouraged people to celebrate Victory Day on February 11 and turn out to vote in the parliamentary elections as a sign of popular confidence in the regime (they didn’t). It hesitated to quarantine Qom. And only at the last minute did it warn against large gatherings for Nowruz, the Persian New Year, in March. This comes on top of the shooting down by Iranian air-defenses in January of a civilian airliner taking off from Tehran airport and the brutal suppression of popular protests last autumn, both of which were met by a similar campaign of denial and obfuscation.

What happens in Iran very quickly spreads to Iraq. That was once an advantage for Tehran. It used its religious and cultural links with the Shia of Iraq to embed its influence virally in the post-2003 political landscape. But real pathogens know no political allegiance. The Iraqi governing class is in turmoil as they seek to manage sustained popular unrest while protecting their own privileges. One prime minister has resigned. A viable replacement is proving hard to find. And the government as a whole — which has never been much good at providing public goods — is in no fit state to provide effective leadership at a time when the issue isn’t the looting of state resources, the use of lethal force against unarmed protestors, the ambitions of sectarian militias or the demands of the IRGC but the health of the entire population.

Iran has better medical provision than Iraq. But that’s not saying much. To judge from social media, both systems seem now to be in a state of collapse. As elsewhere, health professionals are committed and skilled. But politics and corruption get in the way. And no one trusts official announcements. Tehran at first denied that the threat was serious, blamed outsiders for exaggerating the impact and then suggested the US (or Israel or both) had deliberately spread the virus, a lie Khamenei is still repeating. They waited for weeks to shut religious shrines and now still have problems getting people not to visit them. The IRGC has posed as defenders of the people against the virus. But they have also threatened with reprisals doctors who dispute the official statistics.

And, as with other countries in the region, the money simply isn’t there anymore. Energy prices were already under pressure. And Iran’s energy sector has been savagely hit by US sanctions. But the recent decision by the Saudis to punish Russia for refusing to play ball by opening the taps is potentially catastrophic. With oil at or under $30 a barrel, an extra 2.5mbpd from Saudi, plus whatever others decide to produce, will only exert further downward pressure on prices. The IMF thinks the budgets of all energy-producing states in the region are in trouble. Those in Iraq and Iran are in danger of implosion.

The current Iraqi budget assumes an average oil price this year of $56 a barrel. Even at that level, revenues more or less equal current expenditure, two-thirds of it spent on wages and pensions. There is no spare cash for investment and no significant private sector to create meaningful jobs for the huge number of unemployed in the country. The government has simply put many of them on the public payroll. That (and overseas bank accounts) is where the money goes. And now it’s gone.

The same applies more or less to Iran, which has a more diversified if ramshackle private sector but still relies on energy exports to fund the budget. Iraq has a primitive banking sector. Iran’s is unreconstructed and opaque. Neither state has the ability to borrow long term. And even if they did, that would simply represent another burden on the public finances.

In theory at least Saudi Arabia faces a similar challenge. And this crisis will certainly make Mohammad bin Salman’s Vision 2030 that much harder to achieve. But Riyadh can produce up to 12mb of oil a day, maybe more at a pinch, and still has significant financial reserves. It can also borrow on domestic and international markets. It has other significant natural resources and a highly developed health infrastructure. Perhaps because of the lessons of the Mers outbreak in 2012, it acted fast and early in closing mosques, schools and shopping malls, quarantining parts of the Eastern Province — and now Riyadh, Mecca and Medina — and restricting international and much domestic movement. It has just declared a curfew from 7 p.m. to 6 a.m. The suspension of ‘Umrah (the lesser pilgrimage) and the cancellation of the Hajj this year (if it happens) will hit tourism revenues hard. But that’s a one-off. The other Arab Gulf States have acted with a similar sense of urgency and responsibility, with most of them effectively closing their borders to non-nationals and the UAE and Qatar quickly shutting down their airlines, normally a cause for national pride but now simply draining cash.

But Yemen is at high risk of collapse. Lebanon has defaulted on its external debt and is functionally bankrupt. Syria is destroyed. Libya has fallen apart. The demographic displacement produced by conflict in these countries provides an ideal environment for viruses to spread; as does Gaza, one of the most densely-populated places on the planet.

Elsewhere Algeria is in slow-motion turmoil: the government has banned protests because of the crisis but the underlying problems haven’t disappeared any more than in Tunisia. Jordan has acted decisively but is economically fragile at the best of times. Egypt is in denial, seeking to suppress press reporting it doesn’t like and threatening those who question the official bromides issued by the government.

Even for the Gulf, this crisis has brought many challenges into even sharper focus. Governments know they need to reduce government spending and promote private enterprise. Progress in achieving these goals has been patchy. Since patronage brings power, it’s hard to kick the habit. But since we’re probably in for a period of lower economic growth generally and given the costs to any government of balancing budgets in challenging times, it would now be even less sensible for the Gulf to rely on current revenue, financial reserves or their credit rating to take the strain.

Before the crisis, the IMF estimated that if current fiscal positions were maintained, the six Gulf monarchies — which together currently hold $2 trillion of assets — would become net borrowers around 2034. The net financial assets of Saudi Arabia — the single largest Arab Gulf state — are already down to 0.1 percent of GDP from around 50 percent at the end of 2018. Even with oil in the range of $50-$55 a barrel, by 2024 Riyadh’s reserves would only cover around five months of imports.

The outlook for hydrocarbons looks even more uncertain now than it once did. Relying on volatile energy markets for economic growth is unwise. Productive growth in the non-oil sector is needed to soak up the millions of young people coming onto the jobs market each year. That’s going to cost money. The expectations of Gulf nationals that their governments would look after all their needs from the cradle to the grave already looked outdated. Now they seem delusional.

There’s also the issue of competence. Whatever you think of western politicians, they are leaders of institutional states of law with an array of experts on hand to give informed advice and counsel. And even though there is a lack of clarity about the most appropriate responses in different countries (including our own), at least for the moment even Trump seems to be listening to what they say.

That’s not always the case in the Middle East — not because experts don’t exist: they do. But in authoritarian political cultures, they struggle to be heard. We’ve seen this spectacularly in China where, whatever the recent successes of the government’s draconian actions, its refusal to listen initially to the experts on the ground — and to admit what was happening – meant we collectively lost weeks in response time. Iran’s government has been secretive and incompetent too. Iraq’s government is non-existent at the moment and not much good at the best of times. Much the same goes for Lebanon. The Gulf states have done a lot better. But it’s a strain to have to be competent across so many issues all the time.

Once this is over, the choices are going to be stark. The real lesson of this crisis is likely to be that governments simply cannot do everything, whatever some commentators might claim about the virtues of nationalizing the whole economy. Either governments become more competent, trust civil society and take a more selective — dare I say Oakeshottian — view of their role as enablers not controllers. Or they try to continue in the same old way. There are some signs of a willingness to change. The Saudis are preparing to cut government spending while funding a package of support for the SME sector. Sharp falls in royalties from Aramco will refocus minds on the company’s role in the reform program. The UAE is investing in education and AI. And they are both ahead of the pack in many other ways — at least in their stated ambitions, which are clearly on the right track (whatever we may think of actual implementation).

There are reasons to think the other Gulf monarchies will follow suit. But it’s going to be tough. And there is precious little sign that anyone else is capable of making this switch — or even wants to do so. After all, the standard model of the Middle Eastern state is not a Hobbesian sovereign but an unaccountable patriarch. And letting go of this role, with all the benefits it brings — even when it’s clear that the state isn’t up to the job – is very difficult. Rulers don’t need to read Tocqueville to know instinctively that loosening the reins of control is a risky business for autocracies or neo-mameluke oligarchies.

Iran certainly shows little sign of changing course. Oil exports might have crashed. Real incomes are in steady decline. The middle class is shrinking. The government has sought emergency help from the IMF for the first time since the Revolution. They have welcomed humanitarian assistance from the UAE, Qatar and Kuwait. And Khamenei and Rouhani have at least stopped claiming the IRGC is developing a vaccine. But against all the evidence they also publicly praise their own efforts while seeking to heap blame on the US. To buy temporary social peace they may actually have given up on containing the pandemic. At the same time they have doubled down on conspiracies alleging the US military and the Jews are waging biological warfare, something the ignorant and the Islamist — Sunni and Shia alike — are alarmingly ready to echo, especially now they can no longer convincingly claim that the virus is one of God’s soldiers sent to punish the infidel and the wicked.

Instead Iran is focusing on strong-arming Iraqi politicians into choosing their preferred candidate as prime minister so he can expel US forces. Ali Shamkhani, the Secretary-General of the Supreme National Security Council, has recently been out and about in Baghdad to knock heads together. Ismail Qa’ani, Qasim Soleimani’s successor as commander of the IRGC’s Quds Force, isn’t the self-isolating type either. He’s been spotted touring Syria. And he’s just been to Baghdad. Against expert advice, the borders between the three countries — and into Lebanon — remain highly porous. And there are reports that the IRGC are encouraging a new organization inside Iraq to continue attacks on US forces while pretending it wasn’t them or their pals in the Popular Mobilization Forces. They clearly don’t see why a global health crisis should stop the rockets. Perhaps they think all those Islamic State killers the US have been fighting will instead catch coronavirus and obligingly die once American troops have gone.

But reality must eventually catch up even with ostriches. The crisis will mercilessly expose existing weaknesses and accelerate and amplify existing trends everywhere. And the indicators in the Middle East are mostly flashing red. Conflict won’t end and over-centralized states will struggle to reform. It’s possible, I suppose, that the crisis will give some of them a renewed incentive. One interesting case to watch is Israel, where inter-communal cooperation with the Palestinian authorities has worked surprisingly well so far, in spite of the messiness of Israeli politics at the moment. But that will probably be temporary. And Gaza remains a concern.

Where the only lesson learnt is that for things to stay the same they must never change, then popular consent will become even harder to buy. It’s unlikely that the US or other western powers will feel any more sympathetic towards the region once the pandemic is over, whether Trump wins in November or not. That leaves few other potential international partners except for China — where the virus originated and whose cynically neo-imperial ambitions have become even clearer over the past few weeks — and Russia, which has sponsored the destruction of Syria and decided to cut up rough on energy. It’s not looking good.

What position the UK should take on all this once the fog clears is really a question about our appetite for the world. That remains a very open question. But assuming we actually want to reassert ourselves once more in the not so distant future, I offer the following thoughts:

- Don’t bet on Iran, in spite of all the siren voices telling us that this ancient civilization should be our regional partner of choice. The incompetence and malice of its government have become clearer over the last six months. Even in areas where they have shown competence in a bad cause — in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon — this crisis will accelerate breakdown. And my guess is that it will persuade even more Iranians that they need political change. That can only happen from within. But there’s no reason why we should give Khamenei a break while we wait

- If we really want to frustrate him, Iraq is a good place to start. He and his sectarian Shia friends want the US (and therefore us and the French) out. I don’t see why we should oblige. Half the Iraqi political class wants us to stay and help, though they can’t really say so. Leave the field clear for Tehran and Iraq will become a slave state

- It is in our interests that the Arab monarchies of the Gulf use this crisis to accelerate domestic reform. This isn’t a popularity contest, so it doesn’t matter if right-thinking people in Islington and Hampstead don’t much care for MbS or MbZ. I’m not wild about Merkel but understand that she’s not Germany and Germany matters. It’s about making sure that at least one bit of the Middle East and North Africa works and prospers. The Arab Gulf isn’t perfect. But it does work. And it’s prosperous. That’s good for us. But it will only stay that way and work better for Gulf nationals and for us if governments there become leaner, trust their citizens and make their economies more diverse, resilient and sustainable. Find a good way to have that conversation without preaching. And offer to help

- Don’t trust China. Ever. This doesn’t mean not doing stuff that’s in our mutual interest. But we need to make damn sure it really is. Meanwhile distrust and verify

Sir John Jenkins is a Senior Fellow at Policy Exchange and has served as UK Ambassador to Syria, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, and was the Foreign Office’s Director for the Middle East and North Africa. This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.