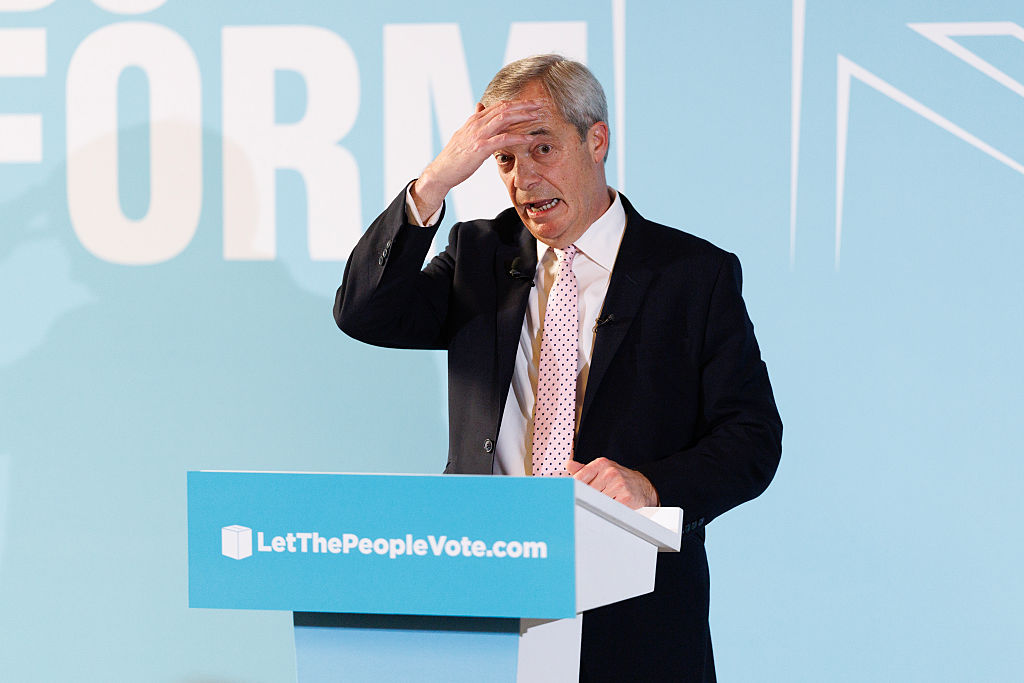

The worse things are for the Tories, the better for Boris Johnson. If the Conservatives were ahead in the polls, he’d have little hope of becoming leader. MPs would choose someone more clubbable, less divisive, and more interested in them personally: who didn’t annoy so many of them so much. But Tory MPs are now contemplating an existential crisis. Tory voters are defecting en masse to Nigel Farage’s Brexit party. The Conservative party’s survival may well turn on winning these voters back, and the former foreign secretary — the tribune of Leave, the buccaneering Brexiteer, the darling of the grassroots — is the most obvious person to do that. Suddenly, Boris is back and in contention for the leadership again. The question now is: can he do what it takes to win?

Ever since Theresa May lost the Tory majority in 2017, her departure has seemed inevitable. The question has been when she’d go, not if. She has survived longer than anyone expected, but now the end really is near. She’s promised to hold a vote on her Withdrawal Agreement Bill next month. If it is defeated, as nearly everyone expects, it will be over: she’ll have no options left. If by some miracle it passes, she has promised to resign once the legislation is through. Whatever happens, the Tories will have a new leader by the autumn at the latest.

Under Tory rules, the MPs choose two candidates and the members choose a winner. No one doubts that, if Johnson can do enough to make it to the membership, he’d triumph. ‘The only person who can stop Boris is Boris,’ is how one experienced hand at the heart of government puts it. But many of his detractors, and even some of his supporters, think he can do just that.

No one has forgotten the drama last time: he didn’t manage to get a campaign organized in the days after the EU referendum. His campaign manager, Michael Gove, ended up deciding to run on the day Johnson was meant to launch his own campaign — and, in doing so, declared the candidate fundamentally unfit for office. But even if he hadn’t done so, Boris still might have failed. He had far fewer MPs on board than expected. Far from being too obsessed with his own leadership ambitions, Johnson, who as a boy told his family that he wanted to be ‘world king’, had not realized until too late that a victory for Leave would lead to an immediate Tory leadership race.

Which, for many MPs, raises the big question about Boris Johnson: he is a gifted communicator, a proven winner (at least in London mayoral elections), but does he have the judgment, guile and self-discipline needed for No. 10? His decision to go off and play cricket the day after David Cameron announced his resignation made it all too easy for Theresa May’s team to get ahead of him. But it also seemed to speak to Boris’s fundamental ambivalence: did he want the job or not? When his campaign team took him to mingle with MPs, he looked like he’d rather be having root-canal surgery. He didn’t even seem enthusiastic about writing his speech for the launch of his leadership bid, taking every opportunity to delay doing so. It all added to an amateur-hour feel that ripped the campaign apart.

Perhaps most telling was his decision to drop out on the morning of his launch. Yes, he had been taken aback by Gove flipping on him, and Lynton Crosby, the Australian political strategist, was advising him to walk away. But as one of his supporters said to me that morning, ‘He wouldn’t stoop to pick up the crown’. The feeling, for many MPs, was that if Boris Johnson had really wanted the job he would have stayed in the race.

Those close to Boris admit that he was naïve about how easily it would all fall into place — and deeply rattled by the ferocity of the backlash to Brexit’s victory. He had gone from being the capital’s Olympic mascot to having hundreds of people outside his home shouting abuse. Worse, many of his own friends and family were furious about the referendum result, and not shy about letting him know. Given Boris’s near-pathological desire to be liked, this shook him badly.

But those who spend the most time with him say that he’s now more determined. That he is reconciled to being a hate figure for many Remainers, less anxious to be liked — and more prepared to take on officialdom. ‘Being outside the system has made him more gung-ho,’ says someone who knows him well. He has also come to terms with his new status as a pariah in bien pensant society. In private, he jokes about how he now receives ‘ABC1 abuse’.

He has started to draft a personal manifesto. Top of the list would be reforming the government machine, which he regards as much of a priority as delivering Brexit and defeating Corbyn. He knows now, in a way he did not in 2016, what he’ll be up against. He’s had his pride pricked by the boasts of civil servants, who have said it was easy to pull the wool over his eyes when the Northern Irish backstop was agreed.

Another sign of the former foreign secretary’s greater preparedness is that his Daily Telegraph column, his weekly address to the Tory selectorate, is now consistently on the same theme: how Corbynite economics cannot generate the tax revenue public services need. The contrast Boris draws between his brand of one-nation Toryism and Corbynism impresses even those who’ll never vote for him in the coming contest. One cabinet minister tells me that, on domestic policy, ‘Boris has the right message but he’s the wrong person to deliver it. He’s too divisive now because of burkas and Brexit.’

He has built more of a relationship with Tory MPs. Last time, he found the whole exercise of asking MPs for their support surprisingly difficult: he is shy in many ways and didn’t take naturally to talking to his colleagues. As one former colleague puts it, ‘He receives offers of friendship rather than making friends’. But with the entire domestic agenda up for grabs following the failure of May’s manifesto, he now feels there is something to talk about beyond his desire for their vote. It also helps that nearly everyone in Westminster is relieved to discuss subjects other than Brexit. But Johnson is almost certainly being over-optimistic when he tells MPs that domestic policy can unite the party. The Brexit divides are too deep for that.

The Boris of 2019 is leaner than the Boris of 2016. He has lost a considerable amount of weight, his hair is behaving itself and he doesn’t look as exhausted. But those who know him well still have their doubts and frustrations. He is still not as good as other candidates at pressing the flesh or feigning interest in others. More worryingly, there are still multiple voices in his ear, and some allies fear he is unable to decide whose advice to take. As one puts it: ‘No one knows who is in charge, because no one is in charge.’

He has always liked having multiple advisers, rather than being pinned down by one. But given the ferocity of the ‘anyone but Boris’ effort from MPs who loathe him, he will need a campaign that can respond quickly and calmly under pressure. That requires someone in charge who isn’t being second-guessed by anybody else.

During the referendum campaign, Johnson delivered Vote Leave’s messages with brio. He accepted that certain slogans were the ones that worked even if they weren’t his first choice. But he only started doing this towards the end of the campaign. He spent the first month or two after he declared for Leave being far less disciplined than that. In this contest, he won’t have time for that. He will have to be on it from the get-go.

Of course, becoming Tory leader will be the easy part. The next prime minister will walk into No. 10 to find a political crisis waiting for them: Brexit not delivered, no effective government majority in parliament, Nigel Farage and his Brexit party rampant and the EU adamant that there can be no changes to the withdrawal agreement. The idea of Boris Johnson as prime minister would be regarded with horror by other European leaders, many of whom see him as the personification of irresponsible populism. Those in the EU who want to punish the UK for leaving would be empowered by his ascent.

Those close to Boris counter that a prime minister who is willing to threaten no deal would give the country back some negotiating leverage. Britain under Johnson would be in a better position to secure some changes to the deal, they say. Then there’s the point that, with a Brexiteer in charge, any withdrawal agreement would feel very different.

But any prime minister willing to pursue a no deal strategy would have to be prepared to go for a general election if necessary, to overcome an attempted parliamentary veto. The problem there would be that Farage and his Brexit party wouldn’t stand down in such a contest, meaning that the election would be highly unpredictable and could even result in Brexit being lost altogether.

Had the Boris Johnson of 2019 been around in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 referendum, history would have played out very differently. The United Kingdom would have had a Brexiteer prime minister who wouldn’t have approached leaving as a damage-limitation exercise. There would have been someone with the political skills to use a general election to strengthen their negotiating position, not weaken it. Above all, there would have been a leader who knew what he wanted Britain to be after Brexit.

The question now is, whether — at this moment — Boris Johnson is the right person for the job. That whether, to use one of his analogies, he has what it takes to seize the ball that has come loose from the scrum. There’s a strong case to be made that he is the Tory best suited to taking on Farage and putting a smile back on the faces of Tory members. But the danger for the Tories is that in making him leader, they might be trying simply to win back voters who have gone while at the same time alienating some of their more Remain-inclined supporters. The strong emotions that Johnson arouses cut both ways. There remains a question mark over whether he could maintain the constant discipline a prime minister needs and whether it is too late for his approach to the Brexit negotiations.

But there is no doubt that this man whose political obituary has been written so many times is not only back in contention but is, now, the man to beat.