China’s Chang’e-6 Moon mission was launched on May 3. It reached lunar orbit a few days later and began waiting for sunrise over its landing site on the Moon’s far side. Chang’e-6 is named after the Chinese goddess of the Moon and it will land on Sunday in a crater called Apollo — an ancient double-ringed walled plain caused by an asteroid smashing into the young Moon. Apollo has been heavily damaged by subsequent impacts and in many places covered with lava flows and sprinkled with particles from newer impacts. It is as Buzz Aldrin said, a magnificent desolation. It is a region of great geological significance, since it contains rocks from the Moon’s lower crust and the deeper mantle — a treasure trove of planetary history.

China has realized what the US forgot, at least until recently: that the Moon is a special kind of prize

Chang’e-6 hopes to bring back rocks from the far side to Earth. Testing the composition of the soil could help narrow down theories about how both the Moon and the solar system formed. But Chang’e also plans to raise the Chinese communist flag over the crater, and the symbolism of this has not gone unnoticed. The flag of the CCP will preside over a site named after the US Moon landings. Nearby are craters named after fallen American astronauts, specifically the crew of ill-fated Space Shuttle Columbia. It’s a symbolic gesture certainly but also a literal one, for the far side of the Moon — which never sees Earth — belongs to China, the only country to have landed there, and the only country since the former USSR in 1976 to have brought back samples from the Moon.

China has realized what the United States forgot, at least until recently: that the Moon is a special kind of prize. We all see it above us, and when we do, China wants everyone, especially its own people, to think about Chinese ambition and its glorious future, not America’s past triumphs.

There is none of the nostalgia the West specializes in here. The rhetoric China uses is all forward-looking. “To explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry and build China into a space power is our eternal dream,” President Xi Jinping has said. “The space dream is part of the dream to make China stronger.”

It’s true that China seems to care more about the Moon than the US does. America has Houston and the space coast, but China has Deep Space Science City in Anhui province, and has cultivated a space zeal among its people that compares with the patriotic fever in the USSR about Yuri Gagarin in 1961. Even during the Moon landings, the US never had the kind of national support that China’s space effort seems to have.

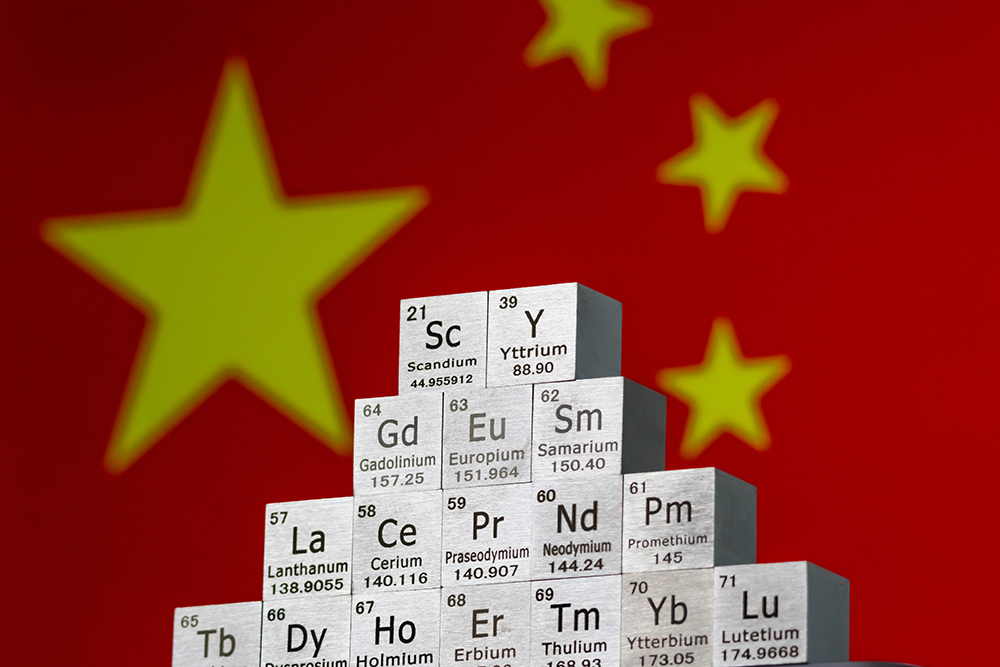

To an extent, this is America’s own fault. China is banned by US law from cooperating with NASA or any US company, for fear of technological secrets being revealed. At one time China hoped to dock its spacecraft — a Russian Soyuz derivative — with the International Space Station and was insulted when permission was refused.

But they proceeded independently and sought non-US collaboration, particularly with the twenty-two nations that form the European Space Agency. Chang’e-6 itself contains equipment from France, Italy, Sweden and Pakistan. China’s Belt and Road initiative has spread to outer space.

China sees that NASA’s Artemis initiative — to return humans to the Moon — is slipping. The Artemis 2 mission plan was to send four astronauts around the Moon but it has been delayed by a year and is set for late 2025. Artemis 3 — the landing — was set for one or two years later, but it now seems inevitable that this mission will simply be an Earth-orbit test. The human landing could be in 2027 or later. China has said it intends to put its astronauts on the Moon by 2030, but those ambitions will probably accelerate as Nasa’s slow down.

NASA insists publicly that the delays are due only to the need to develop the infrastructure to stay on the Moon for extended periods and build a moonbase. But inside the agency many are worried. It’s true that if China carries out a manned Apollo-type mission, it will only be repeating what the US did more than fifty years ago. But unlike the USA in the 1970s, once it’s landed, China has no intention of turning away from the Moon or from space.

The International Space Station is in its final years. It will be replaced by a series of smaller stations built by private enterprise, but they are still in their very early stages. China’s Tiangong (“Sky Palace”), launched in 2021, is still in its assembly phase, but soon it could be the only major space station circling Earth.

Then, of course, there are military considerations. In the future space will play a more active and integrated role. The traditional surveillance orbits will give way to space assets which can be hidden from view until they are needed. China has already demonstrated unhackable quantum communications from space.

Looking back at the space race between the US and the USSR in the 1960s, it is obvious that progress is made very quickly when there is competition. The major space superpowers are well aware of the urgency, but only China can expand its space exploration free from democratic restrictions. There is a new space race now — and this time the US might not win.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply