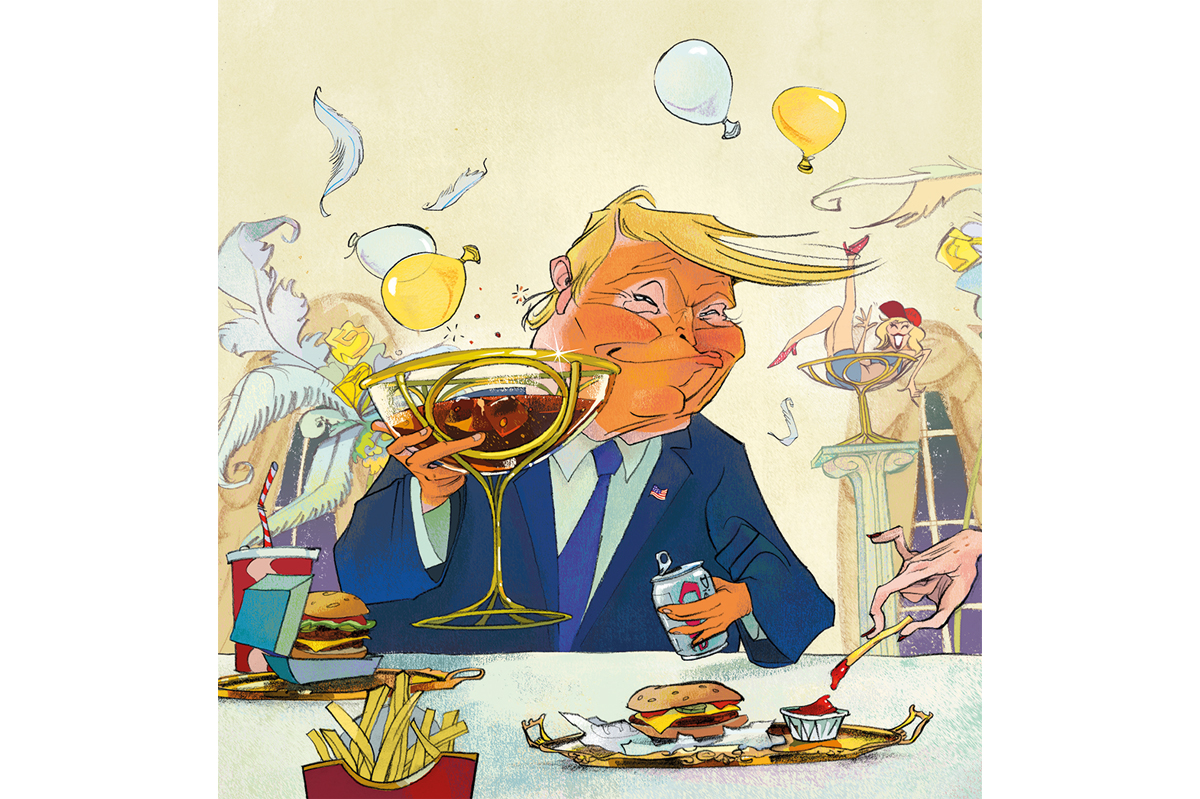

After a year of speculation about how Keir Starmer would work with Donald Trump, the situation stateside has changed dramatically. Gone is the flailing Joe Biden as the Democratic presidential candidate; in his place is Kamala Harris, his resurgent vice president. She enters her party’s national convention as the bookmakers’ favorite to win the White House, with polls suggesting she has a slim lead over Trump. The change in momentum is privately welcomed by most Labour ministers, who would prefer working with a president who hails from their sister party across the pond. Both Starmer and Harris share a legal background and face shared challenges on crime, migration, and unorthodox opponents. Yet while a Democratic victory is the preferred choice of much of Whitehall, it may be hard for Starmer’s team to forge the kind of close bonds which other premiers and presidents have shared in the past.

The next three months will be a difficult balancing act for the British government. As foreign secretary, David Lammy has been keen to present himself as a pragmatist. He boasted last month of his “common ground” with J.D. Vance, declaring “We will work with whomever the United States choose to put in the White House.” Such talk is understandable, given the urgent need to build ties with Trump after the posturing of Lammy and others during the Corbyn years. Yet the risk is that in doing so, Lammy could alienate and irritate Harris’s team. Her campaign is invested in depicting Trump and Vance as extreme, unstable and simply “weird.” Any moves to normalize Trump will go down badly with the Democrats, who are extremely sensitive about any sense that US allies are preparing for life with Trump.

There is a warning here from 1992 — the last time a presidential contest and a general election fell in the same year. John Major won re-election that April but his fellow conservative George H.W. Bush lost to underdog Bill Clinton seven months later. The lasting suspicion in some Democrat circles was that Major’s team had been overtly rooting for Bush’s victory. Two Tory panjandrums advised Bush’s team to focus their attacks on Clinton’s character, while the Home Office became embroiled in a row over whether Clinton was a Vietnam “draft dodger.” There is no suggestion that Labour will do anything as overt this time around. But it is a reminder of the risks facing Lammy and the Foreign Office as they try to keep both camps onside in the eighty days left before America heads to the polls.

Should Harris win on November 5, Britain will likely feature less in Harris’s worldview than under Biden. While the president’s team closely followed the debates on the Northern Ireland Protocol, his VP has a much less Eurocentric perspective. She has less experience, exposure and affinity to Europe. Biden is East Coast; Harris is West. He makes much of his Irish ancestry; her heritage is Indian and Jamaican. He is a lifelong foreign policy guy, chairing the Senate’s prestigious committee; she has little experience here and few experts of her own. Her function throughout much of 2022 and 2023 has been Biden’s “surrogate” on the international stage. At last year’s Munich Security Conference, she was, according to one member of the British delegation, the “single least impressive leader” who met with Rishi Sunak. On Europe, “she’s simply not interested,” says another Whitehall veteran.

This does not mean of course that Starmer and his team have nothing to offer Harris. To take one recent example, the UK will inevitably be drawn into the transatlantic debate about social media and Elon Musk’s ownership of X — a subject the vice president takes a keen interest in. But it would be naive to suggest that a Harris victory guarantees Starmer a close relationship with the most powerful officeholder in the western world.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply