When I first started teaching undergraduates at Harvard, the grading system the university employed struck me as very odd. Even ambitious students at top colleges in the United States see it as their job to answer any essay question in the most thorough and reasonable way. They regurgitate the dominant view in scholarly literature in a competent manner. If they pull this off without making major errors, they fully expect to get an A. And with grade inflation rampant in the Ivy League, they usually do.

This attitude has had a significant influence on American public life. If you read an opinion piece in the New York Times or the Washington Post, its basic thesis is often utterly unsurprising. But writers will usually argue in support of their uninspired conclusion in a painstakingly logical manner, building their case by placing one square block atop the other. In American journalism, to be right — or, at any rate, to argue for the position that the right people consider to be reasonable at the time — is much more important than to be brilliant or entertaining.

This stands in stark contrast to the grading scheme — and the implicit value system — I learned as an undergraduate at Cambridge. There, my teachers explained to me that the earnest and methodical essays I initially submitted as an overseas student fresh off the boat (or, rather, fresh off the Ryanair flight) from Germany would, at best, qualify for a high 2:1. To contend for a first, I needed to learn to be ‘brilliant’.

The ingrained habit of proving that they are worthy of a first has shaped the style of many British journalists

Now, it’s basically impossible for any twenty-year-old to give a series of brilliant responses to questions he or she has never seen before during a high-stakes three-hour exam — especially if these essays also have to be correct. And so the most common strategy for getting a first was to argue for positions that are deeply counter-intuitive.

These counter-intuitive answers were often plain wrong, sometimes for reasons that would have been evident to anybody who had studied the topic at hand for more than a week. But that, we were given to understand, wasn’t so grave a sin. As long as we argued for our wrong positions with flair and panache, we had a chance of that coveted first.

Just as in America, this grading system conveyed a particular set of values to students, one that they carry with them as they enter their professional lives. It seems to me, for example, that, for better and for worse, the ingrained habit of proving that they are worthy of a first has shaped the style of many British journalists. Even as the country is getting more polarized, opinion writers care more about being entertaining than about being right. Across the political spectrum, from the Guardian to the Telegraph, columnists have far greater freedoms than their American counterparts to adopt a chatty tone, to float a half-baked idea, or to go off on an entertaining tangent. For American journalists, the cardinal sin is to be wrong. For British journalists, the cardinal sin is to be boring.

It is perhaps inevitable that this attitude has not remained confined to the world of British journalism — and not merely because many journalists, from Winston Churchill to Michael Foot, have gone on to be influential politicians. Take the case of Boris Johnson. Before he became an ardent Brexiteer, he famously hesitated about whether he should join the remain or the leave campaign. And to figure out which way to jump, he wrote two newspaper columns: one supporting and one denouncing the European Union.

Whatever you think of the merits of the case, it isn’t hard to see what drove Johnson’s decision. The case for remaining in the EU was dutiful and boring. It listed economic benefits from which Britain already profited and contained words like “integration” and “geostrategic anxiety.”

The case for leaving the EU, by contrast, was bold and boisterous. It harked back to emotive values like national sovereignty and looked forward to a fresh, golden future. Right or wrong, it would have been far more likely to have got a first.

A few years ago, a viral article claimed that one Oxford degree runs — and perhaps ruins — Britain.

As Andy Beckett pointed out in the Guardian back when David Cameron was prime minister and Ed Miliband led the Labour Party, the upper ranks of the country’s political and journalistic class were filled to the brim with people who, like them, had studied philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) at Oxford. However, it was speculated at the time that the age of PPE might be coming to an end: “In the new age of populism, of revolts against elites and ‘professional politicians,’” Beckett wrote, “Oxford PPE no longer fits into public life as smoothly as it once did… [it] has lost its unquestioned authority.”

But this prediction, like so many others made over the past decade, has turned out to be mistaken. For in the intervening years, the list of powerful PPE graduates has continued to grow at a rapid pace. There’s Rishi Sunak, the current prime minister, Liz Truss, his predecessor, and Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor. On the opposition benches, PPE graduates include Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor and Yvette Cooper, the shadow home secretary. Take the most recent budget: it was (to adapt a similar enumeration from the Guardian’s original criticism) delivered by Hunt (PPE) for Sunak (PPE), reported on by the BBC’s Nick Robinson (PPE), criticized by Reeves (PPE), and commented on by the head of the influential Institute for Fiscal Studies, Paul Johnson (PPE).

Donald Trump thrives because the American political system leaves no space for a Boris Johnson

More broadly, while PPE graduates are indeed phenomenally influential, the influence of the PPE degree seems to me to be overstated. For the most part, its prominence is a result of a selection effect. For the past century, the degree has attracted a large share of the most talented and, well, the most cravenly ambitious people in the country. It is little wonder that many of them went on to win positions of influence and responsibility, with some acquitting themselves admirably, and others failing upwards, blunder after major blunder.

The theory is also far too simplistic. Like virtually all monocausal theories, it implausibly ascribes complicated phenomena like the strengths and shortcomings of Britain’s governing elite to a single origin. And if we do have to engage in such simplistic theorizing (and doing so is admittedly a lot of fun), the habits ingrained by the grading systems at all British universities, not just Oxford, seem to me to be much more plausible candidates.

Each grading system communicates a set of deeper values. And each set of values has both benefits and drawbacks.

America’s value system has helped to create a deeply conformist elite. As early as college, the best-credentialed people in the country learned that the benefits of brilliance or contrariness were low and the best way to get ahead was to be both competent and compliant. This created the Democratic Party of people like Hillary Clinton: candidates and advisors who were deeply fluent in the received wisdom of their time yet failed to appreciate the pulse of their own population. Ones who barely made any misstep but sounded so scripted that they ended up alienating millions.

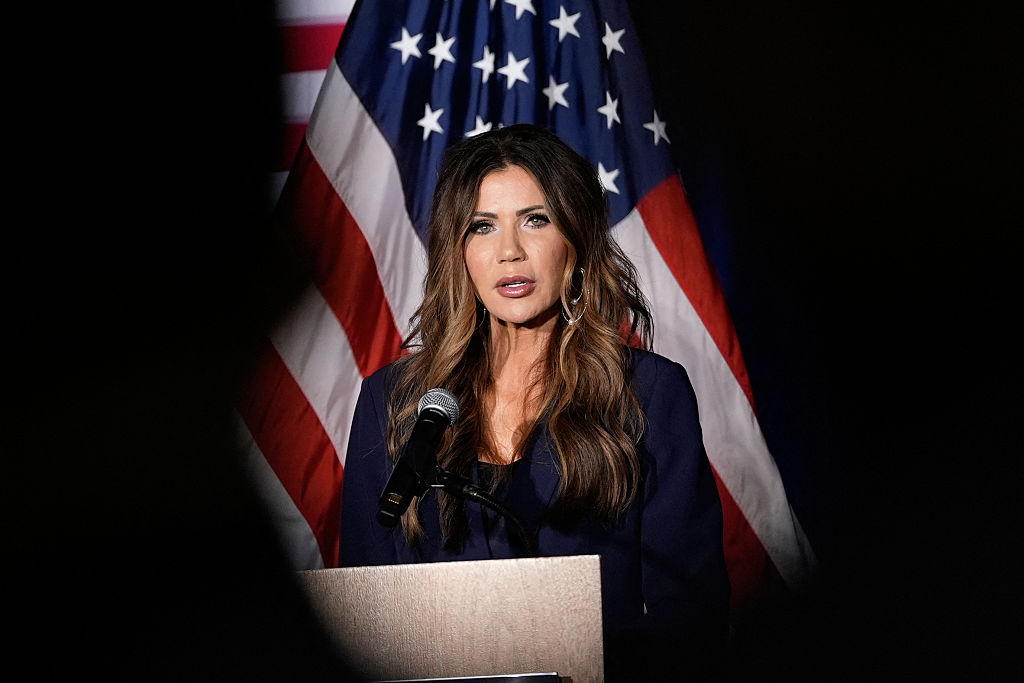

Another drawback of the American system is that it leaves little room for rebellion within the ranks of the country’s elite. Since there is no way to assail the prevailing consensus within the idiom of the elite, any attack on it has to come from the barbarians at the gate. Donald Trump thrives in part because the American political system leaves no space for a Boris Johnson.

A third drawback, of mostly parochial concern, affects the dwindling few of us who still read or write for the mainstream press: the ethos of being accurate and reasonable — which aspiring journalists start to learn in college when they write up an email from the assistant dean for housing for their student newspaper in the same tone and diction in which they will, if all goes according to plan, as it often does, one day write up a presidential press conference at the White House — makes for dreadfully dull and often painfully incurious journalism.

But the value system implicit in Britain’s grading system also has serious drawbacks. It creates a culture in which charismatic amateurs are nearly always prized over earnest professionals; a political system in which cabinet ministers rarely have any deep knowledge about the subjects for which they are responsible; and a broader public culture in which the art of spin is often prized over the imperatives of substance.

If you are the “right sort,” you can get a first in PPE — or many other degrees in the humanities and social sciences — by means of persuasion. But it turns out that an elite that has become habituated to persuading isn’t always good at running major companies, making important inventions, or governing a country.

Is this argument wholly convincing? Would the United Kingdom really be a vastly different country if only its leading universities had happened to adopt a different grading system?

Well, no. Monocausal explanations, as I said, always fail to fully explain complicated phenomena. But even as they short-change reality’s complexity, they can give an argument a run for its money, exposing both its limitations and, sometimes, its kernel of truth.

There is a value in student essays — and even in magazine articles — that shoot for a first. And that is why Britain should, despite its drawbacks, never fully let go of the instinctive preference for the thought–provoking over the reasonable that — along with an allergic reaction to highfalutin bs — characterizes its public culture.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazines. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply