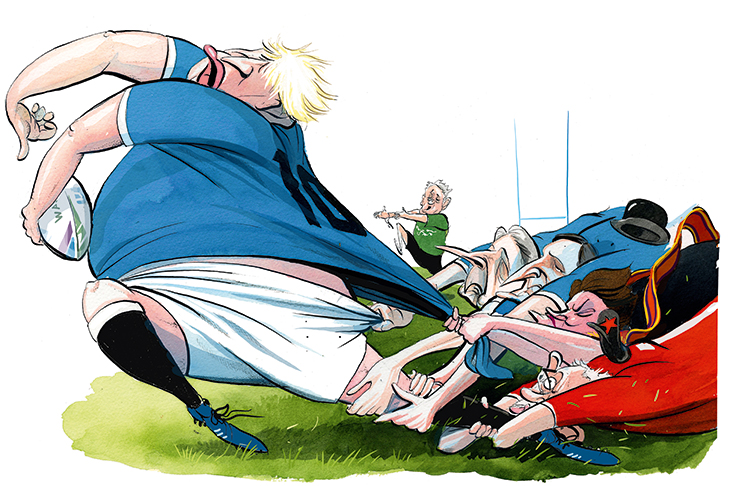

Ever since Boris Johnson became prime minister his opponents — both inside and outside his party — have been convinced that his ‘do or die’ pledge to have the UK out of the EU by October 31 would be his greatest vulnerability. ‘We’ll make him miss this deadline,’ they thought, ‘and his credibility will be shot.’ Brexit party voters would write him off as another blusterer from a Tory party unable to deliver. He seemed to think so too, repeatedly saying that ‘extension means extinction’.

His enemies have now succeeded; the defeat of the government’s Brexit timetable in Tuesday night’s vote means it is near impossible for him to meet that pledge. He might be hoping for a miracle (these can happen, as his deal showed) but parliament has won. It has forced his government to ask for an extension from the EU, and Donald Tusk says he is encouraging EU leaders to grant one.

Yet far from being politically dead, Boris Johnson finds himself in a stronger position than he was on the day he became prime minister. The Brexit deal he has struck with the EU has changed everything. It not only garnered the support of a majority of MPs at its second reading, but more importantly it is a deal that Leavers broadly welcome. Every Tory Brexiteer in the Commons voted for it, every cabinet minister is fully signed up to it; and initial polling suggests that the general public back it too — more say that they support the deal than oppose it. Suddenly the Tories are occupying the common ground of British politics.

This means that despite Johnson’s parliamentary impotence, he is in a strong position for whatever comes next. ‘Everything is now better,’ says a cabinet minister. With the Withdrawal Agreement Bill ‘in limbo’ after MPs rejected the government’s speedy timetable, No. 10 is pushing for a general election.

This would offer Boris Johnson two advantages. First, he can present himself as trying to ‘get Brexit done’ but being thwarted by parliament. Those close to him are now confident that the failure to meet the October 31 deadline won’t hurt him, as voters will see that he brought back a deal against all odds and did all he could to get it through in time.

Secondly, the Brexit deal offers complete reassurance to Tories worried about an imminent no-deal. As the Prime Minister told MPs on Tuesday night: ‘One way or another, we will leave the EU with this deal to which this House has just given its assent.’ A smooth, orderly, amicable Brexit is a much easier sell in those affluent constituencies which the Tories are defending against the Liberal Democrats. The unity can be seen within the parliamentary party, with every single Tory MP this week voting for this deal at second reading; something unimaginable under Theresa May.

No. 10 and Boris Johnson himself have been oddly calm about the deal’s passage through parliament. The panic and pessimism that became typical of May’s Downing Street ahead of a crunch vote has been replaced by a willingness to let the chips fall where they may. The whipless Tories have been surprised at how little pressure they have come under from Downing Street. Several of them haven’t been offered either carrot or stick.

The reason? No. 10 is convinced that, in the words of one source, he ‘wins either way’ in all these votes. Their logic is that the public simply see Boris Johnson trying to ‘get Brexit done’; and if parliament blocks him, his opponents get the blame for delay. Take Monday’s bid to persuade John Bercow to allow a fourth meaningful vote on the Brexit deal. Few in government believed the Speaker would allow such a move, given the parliamentary rules — yet they tried anyway, because it gave the Tories another chance to look as though they were attempting to deliver Brexit against a deadlocked parliament.

This is why No. 10 is now straining at the leash to have a general election. The plan is to pile into Labour-supporting Leave seats in Wales, the West Midlands and the north-east with the message that only by voting Conservative can it be ensured that Britain will leave the EU. They’ll argue that a vote for Labour is a vote for a second referendum tilted in Remain’s favor, and another year of wrangling about Brexit.

Before the new Brexit deal, the Tories had pinned all of their hopes on Labour Leave seats (along with the sense that a fear of a Corbyn government could keep Tories who were jittery about no-deal in the fold). Their plan involved seeking a mandate for a no-deal Brexit while saying that they hoped this threat would make the EU compromise. It was an inherently complicated message. In the words of one of those involved in drawing up Tory electoral strategy, it was ‘a very steep and very narrow road’ to victory.

But the Brexit deal now allows the Tories a two-pronged strategy: they can go on the offensive in Labour Leave seats but still defend their existing constituencies against the Liberal Democrats. They can credibly promise a smooth and orderly exit which paves the way for amicable relations with the European Union. Tory MPs who were pretty much resigned to losing their seats to the Liberal Democrats are far more chipper about their chances now.

The Tories offer a negotiated Brexit deal, freshly baked in Brussels. Labour promises more negotiations and a second referendum, with all the rancor that would bring. Jo Swinson, Lib Dem leader, seeks to revoke Brexit entirely, without a referendum. Nigel Farage’s Brexit party is hellbent on no-deal, saying the Boris plan is not Brexit at all — something even Arron Banks, his former political partner, cannot bring himself to say. In contrast to these positions, the Tory one looks rather reasonable.

At the same time, the Conservatives will seek to start a new conversation on life beyond Brexit, with a manifesto aimed at former Labour voters. No. 10 has sent a memo to Tory aides asking them to submit policy submissions by the end of the week, with a push for policy areas where there is a significant dividing line with Labour along with positions that should be mentioned in a manifesto ‘to avoid negative publicity’. Rather than Gordon Brown-style price tags (‘£20 billion for the NHS!’), spending will be explained in terms of, for example, the number of hospitals it funds. ‘It has to be quantifiable,’ says a party source.

The other Tory hope is that the anti–Brexit vote won’t coalesce around Labour, as it did in 2017, and that the Lib Dem surge might give the Tories a whole slew of seats without the party having to win any more votes. As one cabinet minister puts it, ‘motive matters in politics’; and Leave-supporting voters seem prepared to accept compromises from Boris Johnson that they would have denounced from Theresa May. The Farage vote won’t disappear. But Tory HQ thinks that if they can squeeze it a bit further (down to about 7 percent of the vote) then it will hurt Labour more than them. It is worth remembering that in 2015, the Ukip vote helped the Tories pick up various seats, including Ed Balls’s.

There is, however, one obvious flaw in No. 10’s strategy: the prime minister does not have the power to call a general election. We have been here before. In September, No. 10 pushed for an election only to have opposition parties refuse to play ball. One minister frets that No. 10 is once again forgetting Osborne’s rule: ‘Never expect the opposition to give the government what they want’. The minister puts it another way: ‘Labour aren’t going to vote for an effing election.’

Boris Johnson’s circle have two hopes for how they might get this parliament to dissolve itself. The first is that Jeremy Corbyn takes the bait: he has great faith in his own electioneering ability and has repeatedly said he would back an election once an extension has been secured. The second is that the united opposition front against an election cracks. The Scottish National party will be keen to get going before the Alex Salmond trial, expected early next year. The Liberal Democrats cannot afford to let Brexit outrage cool. If they wanted an election, then the Tories could engineer one.

They will need to move fast if it is to happen this year. Mark Sedwill, the cabinet secretary, has warned that an election after December 12 would be problematic because village halls will be booked up for pantomimes and fairs. One date being discussed by government figures is December 5.

An election next year would be more risky for the Tories. If Britain has left the EU — legally, at least — then Leavers might return to their normal political allegiances. But Remainers would still be emotionally involved, so the Tories could lose many of their 2015 Remainers without making sufficient gains elsewhere to compensate.

Other ministers worry that time might be their enemy. ‘If we wait till the New Year, what if there’s a migrant crisis or a winter health crisis?’ says one. Without knowing when an election would take place, they can’t decide which seats to target. ‘We can’t plan right now — it depends on the outcome of Brexit,’ sighs one senior Tory.

It’s still just possible that the EU will tire of this drama and refuse to grant the UK an extension to membership, or offer only a very short extension. This would force parliament to ratify the withdrawal agreement or face no-deal. A few senior figures in government still hope that Emmanuel Macron will veto a Brexit extension: his impatience with this process is well-known. But that would likely be seen by the EU as interfering too much in UK politics. So parliament would have to agree a new timetable for ratification, or stagger on until the balance of power collapses and a general election is called.

The Tory lead is currently in double digits and ticking up steadily. But the party’s lead was impressive in the last general election, until it evaporated. That was a reminder that any election is a risk — and snap elections especially so. Who would voters blame for having to trek to the polling station in the bleak midwinter? As so often, it all comes down to optimism — the hope that Boris Johnson is a better candidate with a better team, and that he will be able to persuade people that only a vote for the Tories can bring this Brexit pantomime to a close.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.