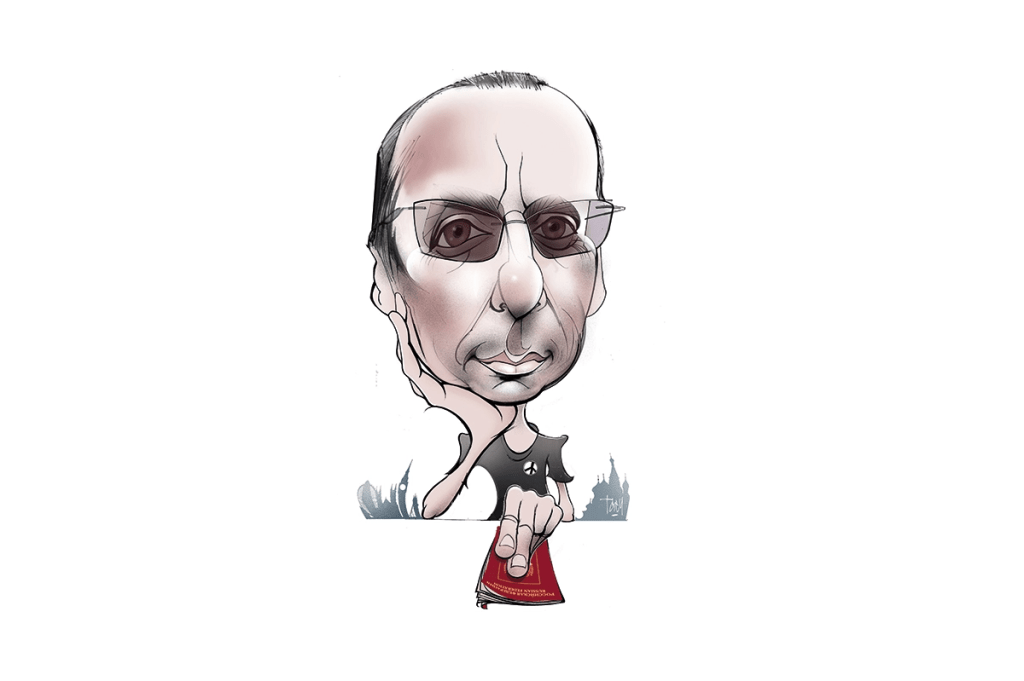

Boris Bondarev’s Twitter profile sums up his past, present and future in three short phrases: “Russian diplomat in exile. Stop the war. The old lie: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” — a quote from Wilfred Owen’s 1918 denunciation of patriotic hypocrisy.

Shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, forty-two-year-old Bondarev quit his job as an arms control expert at Russia’s diplomatic mission to Geneva in protest. None of his colleagues in Geneva, or anywhere else, followed suit (at least not publicly). Does that make Bondarev the only Russian diplomat with a conscience?

“It’s not about conscience,” Bondarev tells me by Zoom from an undisclosed Swiss location where he now lives with his wife and cat. “It’s about courage. Not so much courage to defy political repression, because while there is repression in Russia it’s pretty limited. It’s about the fear of going against the mainstream… nobody wants to be a white crow.”

Though he had resolved to resign in the first weeks of the war, Bondarev handed in his formal resignation only in May, as his wife had insisted on returning to Moscow to collect their cat (the operation required three flights and crossing the Lithuanian border twice on foot). Bondarev then published an open letter against the war on LinkedIn and began tweeting about his opposition to it. Few of his fellow countrymen noticed. Russian state media didn’t mention his defection. When asked about the case by a foreign reporter, presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov did say that Bondarev “is not with us, he is against us… he is critical of the Russian leadership’s policies, which are supported by practically the whole population of our country.” Then — official silence.

Is Bondarev scared that he will suffer the same fate as defector Sergei Skripal and his daughter, poisoned in Salisbury in 2018 with Novichok nerve agent smeared on their door handle? “If they want to do something they will try, but what can I do about it?” shrugs Bondarev, wearing a plain black T-shirt and sitting in front of a blank wall in his apartment. “Security concerns do restrict me a little, but not seriously.” He does, though, look at social media posts of Russians traveling freely around Europe and finds himself envying “those happy people.” The Bondarevs received political asylum in Switzerland, but it will be at least a decade before they can get citizenship and travel on anything but their (still uncanceled) Russian diplomatic passports.

By quitting his job and coming out publicly against the war, Bondarev blew up not only his career but also his ties with family and friends back in Russia. His father, a Soviet bureaucrat turned businessman, was once a passionate supporter of Boris Yeltsin, privatization and democracy — and even advised his son not to vote for Vladimir Putin in 2000. Like millions of Russians, his father “believed the West would help us, help us build democracy,” says Bondarev. “But all we got was a catastrophic drop in standards of living, [along with] criminality and anarchy.”

By the time of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February last year, Bondarev’s father was so convinced that Putin was right that he went to his local recruiting office and tried to sign up for the army, despite being seventy-five years old. “You see the evolution in a person’s head,” said Bondarev. “My father doesn’t watch state TV, he says it’s all propaganda. But he finds information on YouTube that repeats everything that the Kremlin says. That’s how well [state] propaganda works.” When his diplomat son announced his resignation, Bondarev senior called to tell him that “you don’t see the full picture. Putin does.” Bondarev hardly calls his parents or Moscow friends any more. “I wouldn’t want to cause problems for them,” he says.

Only one senior Kremlin official — former finance minister and Yeltsin chief of staff Anatoly Chubais — has so far publicly resigned over the war. Bondarev claims that “many” Russian bureaucrats, including diplomats, have resigned, but quietly. “If I had been in Moscow when the war broke out, I am not sure I would have made a public statement,” he admits. “I knew that few people would listen — and then I would have gone to prison or sat without work and without prospects. There are people who want to speak out, but they weigh the risks and it’s understandable that they see that the risks are far greater than what they will gain. There is no upside to speaking out.”

No upside — except that Russians’ silence implies consent to Putin’s vicious war. Does Bondarev believe that the Russian people bear some responsibility for the actions of their government? “That’s a philosophical question,” says Bondarev. “Are the German people guilty for World War Two? People who ask that question usually want a simple answer — yes, all Russian people are guilty… But you can’t demand that Russians rise up against Putin, at the height of his powers and in command of a massive apparatus of repression, and go against him with their bare hands.” He points out that many Europeans — including the Spanish and Portuguese — complied meekly with dictatorship for decades, rising only when their fascist leaders were dead.

At the same time Bondarev admits that Russian officials are “extremely servile” and “pathologically afraid of taking any responsibility, which is why there is this culture of ‘the master always knows best’” — as Bondarev saw over a twenty-year career in the Russian Foreign Ministry. “Government service is heavily built on conformism… the boss always right, and you have no right to your own opinion.” In conversations with his diplomatic colleagues in Geneva after the war broke out, Bondarev found that most just “shrugged and said, ‘What can we do about it?’” — before going out in public and “tearing their shirts as they passionately shouted that Ukraine wanted to attack Russia with bio-weaponized mosquitos, or some nonsense.”

How does Bondarev answer people who accuse him of betraying his country? By quoting “two great Russian classics,” the nineteenth=century satirist (and deputy governor of Tver) Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, who wrote that “some people confuse the Motherland with His Excellency,” and the cult St. Petersburg singer Yuri Shevchuk, who told a concert audience recently that Russia “is not the same as the ass of the president.” For Bondarev, “true patriotism is a desire for your country to live well, for its people to live well. Not necessarily better than other countries. But to understand that, you need to know the difference between good and evil. You need to switch on your brain. Patriotism without brains is what we see in today’s Russia. Patriotism with brains is what you have in Switzerland, where nobody thinks of attacking any other countries or proving anything to anyone. They simply live better than anyone else in the world, and that’s it.”

Bondarev believes that Russians’ historical fascination with national greatness over personal quality of life was the fatal flaw that Putin and his clan exploited to their own ends — creating the “disease” of nationalism that now ails the country. Putin “was a plain KGB officer, he was used to seeing enemies everywhere, plots,” says Bondarev. “If a brick falls on your head it’s not something that just happened, it’s someone trying to harm you.” But the security state Putin built was based on “changing the Yeltsin oligarchs for his own oligarchs, strengthening his power by creating a mafia government… the system was unable to create anything or build anything except selling off commodities like oil.”

The only true governing philosophy of Putin-era bureaucrats is “we steal enough for all our lives, and three lives ahead of us, and you all sit quiet. But you can’t sell that as an idea to people, so you have to come up with some other nonsense to sell them.” For instance, that Russia is under attack from NATO, or that Ukraine has been taken over by a fascist regime. Putin needed the war for the practical, objective reason of “distracting people from the fact that they had no future and to preserve his own power” — as well as for a “subjective, personal fantasy that he could be like Peter the Great and restore Russian greatness.”

In common with many Russian diplomats and even very senior officials, Bondarev did not believe that Putin would actually launch the invasion. Instead, he thought that the massive build-up of forces on Ukraine’s borders was huge bluff “to force Ukraine and the West into making some kind of concessions.” But once the war began Bondarev says he knew it would go badly. “I always believed that Ukraine was much stronger than our propaganda claimed, that our army and military production was much weaker, and that nobody in Ukraine would greet Russian troops with flowers.”

Now, after nearly a year of bloody conflict, Bondarev’s colleagues in the Foreign Ministry who at first greeted the invasion with “a kind of bureaucratic delight” are “experiencing doubts now that they see that the war is not as wonderful as they had imagined,” he says. Nonetheless, he as yet sees no prospect of serious discontent that could challenge the regime.

For now, Bondarev inhabits a tragic kind of limbo, spending his days feuding on Twitter with both pro-Kremlin trolls and anti-Russian Europeans. He recently criticized a tweet by the Lithuanian foreign minister celebrating “our” victory over Soviet tanks in 1991 as being the same as modern Russians claiming credit for victory in World War Twp because the minister was eight years old at the time. In response, many Twitterati piled in to denounce Bondarev as a “Russian imperialist.” Exiled and alienated from his home country for his principled stance, for many Europeans Bondarev’s original and apparently unforgivable sin is having been born Russian — and to have served the regime loyally for two decades before finally deciding that enough was enough.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.