The outbreak of fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the weekend is the latest episode in a saga stretching back to the waning years of the USSR. Although recognized as being part of Azerbaijan, the region of Nagorno-Karabakh is a de facto independent zone populated by ethnic Armenians. Its independence came as a result of a war between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse; while this ended in the mid-1990s in a victory for the Armenian-backed separatists, sporadic fighting has plagued the area ever since.

This has most often taken the form of localized artillery duels, but this July witnessed the heaviest exchanges since the war itself, with shelling resulting in dozens of casualties. Azerbaijan reported the loss of a major-general, colonel, and an entire squad of special operations troops. Although a ceasefire was tentatively restored, 30,000 residents of Baku took to the streets to express their anger at the stalemate and demand the full mobilization of the military.

This has now come to pass — in the wake of Azerbaijan’s full-scale assault against Armenian defensive positions in the region, both countries have ordered a general mobilization of their militaries. As nations highly reliant on conscript troops, their forces will soon swell considerably. The fighting has already been fierce, with reports of downed helicopters, destroyed tanks, and night skirmishes.

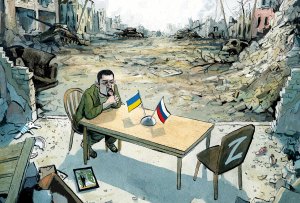

The European Union and Nato have, predictably enough, expressed ‘deep concern’ over the events, but the most decisive actors remain Turkey and Russia.

Turkey’s close ties with Azerbaijan are not only a result of shared political ambition but are also deeply rooted in culture and history: the Azerbaijanis are part of the Turkic ethnic family, whose language is even somewhat mutually intelligible with Turkish. Indeed, Turkey often proclaims that the countries are ‘two states, one nation’, the most recent declaration of which came on September 7, and Azerbaijan staunchly refuses to follow the example of Europe and the US in recognizing the Armenian Genocide.

Russia, for its part, has long been an ally of Armenia and even retains a military base within its territory. Its presence is tolerated since, according to opinion polls, Russia’s support in the face of Turkish or Azerbaijani aggression would guarantee the country’s safety.

This notion is now being put to the test.

Turkey’s Erdogan has been emphatic in his support for Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, stating that: ‘the Turkish people will stand with their Azeri brothers with all their means’. It would be deeply unwise for Armenia to discount the possibility of Turkish military intervention — not least when Turkish drones have been sighted on Armenia’s western borders.

Of course, when dealing with reactionary and ruthless politicians in the form of Aliyev, Putin and Erdogan, it would be foolish to rule out anything, and the international sense of unease is entirely justified. Certainly neighboring Georgia is being one of the loudest voices in the call for an immediate ceasefire, as the Georgians know better than most what the results of bringing down the Kremlin’s wrath will be; the country suffered an invasion by Russia in 2008 over its own two separatist states of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. If Russia should become involved in the dispute and seek to reinforce its troops in Armenia, the only land route lies through a diplomatically estranged Georgia.

Yet while Russia is described as an Armenian ally, its relations with the new government in Yerevan have been frostier than with its predecessors. This is principally due to the fact that the incumbent prime minister, Nikol Pashinyan, has been more skeptical of Russia’s influence in Armenia, highlighting potential threats against Armenian sovereignty. Although he has never fully embraced the west and its values in the manner that his Georgian counterparts have, his attempts to chart a more neutral political cause are a departure from the cloyingly close relations of his predecessor, Serzh Sargsyan, who fostered close ties with Moscow throughout his political career.

Armenia’s premier also incurred Putin’s ire in June when he met with senior EU officials and declared that his country remains committed to developing its partnership with Europe ‘based on shared democratic values’ (although Pashinyan himself came to power as a result of a revolution in 2018). An Armenian defeat could bring about the end of the Pashinyan administration and restore Yerevan’s closer ties with Moscow under a government more friendly to the Kremlin.

With this in mind, casting Armenia as ‘Russia-aligned’ and hammering home Azerbaijan’s status as a Turkish ally sets the stage for a potential clash between Ankara and Moscow. However, given Putin’s lukewarm relationship with the Armenian authorities and the careful development of the friendship between Russia and Turkey, it can be assumed that Erdogan would not be so bellicose as to attack Armenia at the risk of souring relations with the Kremlin. Pashinyan himself declared soon after hostilities began that there must be no foreign assistance — his predecessor, as a loyal friend of Moscow, would likely have requested Russian aid.

[special_offer]

The scale of the attack suggests that substantial preparation lay behind it and it is unlikely Azerbaijan would have initiated the fight without Turkish guarantees of support. Erdogan does, in fact, have something to prove on the international stage — despite aggressive rhetoric accompanying August’s tensions between Greece and Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey quietly climbed down when the UAE, Jordan, Egypt and Israeli hinted that their support lay with Athens (the UAE even sent military aircraft to train with their Greek counterparts during the crisis).

Armenia, however, represents a far easier target. Unlike Greece, it is not a Nato member, nor can it rely on powerful alliances in the Middle East. Russia — which has been Armenia’s principal international partner since the fall of the Soviet Union — has called for a cessation of hostilities yet has made no moves to indicate it will side with Yerevan.

Perhaps the only way in which diplomacy can prevail is if international pressure is put on Turkey — only Ankara has the political and military muscle to force an immediate ceasefire, but it has little to lose by worsening the conflict. The west has an opportunity to reestablish its credibility and assert itself. But it will need to do much more than express ‘grave concern’ if it is going to be taken seriously by its rivals — rivals who understand that it is not western strength that is lacking, but western resolve.

This article was originally published on

The Spectator’s UK website.