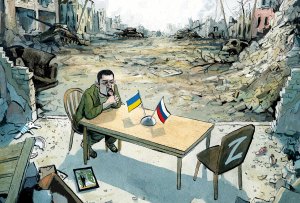

The fight to power eastern Europe is heating up. As Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky prepares to meet Joe Biden at the White House, competition for Ukraine’s energy market is increasingly being framed as a battle between East and West. And as western investments into renewables vie with fossil fuel imports from Russia, the struggle for the nation’s energy supply is assuming a moral dimension reminiscent of the Cold War.

Tens of thousands of panels at Ukraine’s huge Nikopol solar farm harvest the sun’s energy for nobody. In late 2019, the Canadian owners of the farm, TIU Canada, were informed that the nearby Nikopol Ferroalloy Plant, owned by the notorious Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, would be disconnecting their farm from the power grid to make repairs. They were not aware that any such repairs were needed. Despite frantic protests the connection was severed — and a year and a half later, it has still not been restored.

Kolomoisky’s tentacles extend deep into Ukraine’s economy and politics. He controls a faction of MPs without which the current coalition would collapse, as well as the country’s most lucrative energy distributor and, previously, some of its biggest banks. He is a controversial figure who in March 2021 was banned entry to the US over his ‘significant corruption’.

The successful development of the renewable energy sector in eastern Europe would not only undermine Putin’s political influence — it would also take a wrecking ball to the Russian economy.

Kolomoisky’s greed is matched only by his fickleness. He funded Ukrainian forces fighting against Russia during the Crimean War in 2014 — but as the US has taken a greater interest in his affairs over recent years, his allegiances have shifted east. Ukraine’s power broker now argues that the EU and Nato ‘won’t take us, whereas Russia would love to bring us into a new Warsaw Pact.’

This growing alliance with Vladimir Putin has seen Kolomoisky accused of undermining Ukrainian independence from Moscow when it comes to energy. With the 2014 war resulting in the loss of Ukraine’s most coal-rich region to Russia-backed separatists, importing energy has become a key political issue. Despite a ban on Russian gas and numerous attempts to limit the import of other fossil fuels, Russian imports still account for a third of Ukraine’s energy supply. Kolomoisky has successfully reconfigured his energy distributor to focus on buying Russian coal, and in 2020, Russia was the source of 70 percent of Ukrainian coal imports, while most of the country’s oil also comes from Russia and Belarus.

The West simply cannot hope to compete with Russia when it comes to fossil fuel exports to eastern European countries such as Ukraine. And with the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline set to further increase Europe’s energy dependence on Moscow, western countries have no choice but to look further into the future in trying to counter Russian dominance. Through investment into renewable sources of energy — such as the Nikopol solar farm — they see the potential to eventually leapfrog Russia’s enormous fossil-fuel sector.

Indeed, the successful development of the renewable energy sector in eastern Europe would not only undermine Putin’s political influence — it would also take a wrecking ball to the Russian economy. With fossil fuels accounting for two-thirds of Russian exports, the renewable energy revolution could spell economic catastrophe for Moscow.

With this in mind, Ukraine has offered huge subsidies for renewable energy developments since its war with Russia. Angela Merkel was motivated by similar considerations when she promised €1 billion in investments into the Ukrainian renewable sector last week, to help offset the negative security implications of Nord Stream 2. And it is Russia’s heavy dependency on fossil fuel exports which makes eastern European countries view the recent German-American accord on Nord Stream 2 as an act of enormous geopolitical self-harm.

Kolomoisky’s aggression against the Nikopol solar farm is indicative of attempts by Russia-allied forces to undermine this shift to renewables — but there are also other threats to an industry which remains a marginal contributor to Ukrainian electricity generation. Some allege that huge green subsidies have created ‘a new oligarchy’ of unscrupulous investors, while a sharp fall in foreign investment has followed Ukraine’s inability to pay debts incurred by attempts to make the country a destination point for western companies.

Still, portrayals of the Ukrainian energy sector are now assuming a moral dimension which, in equating West vs East with Good vs Evil, are reminiscent of Cold War attitudes. In an animated video explaining their legal dispute with Kolomoisky, the owners of the Nikopol solar farm frame the issue as a straightforward morality tale: an ‘honest investor from Canada’ is attempting to save the ‘hard-working, fair and kind’ people of Nikopol from the clutches of an evil, pro-Russian, fossil-fuel-guzzling oligarch.

This simplistic portrayal encapsulates the way in which the West’s economic interests in the eastern European energy sector neatly align with a sense of moral crusade in encouraging the shift to renewable energy. A time-honored tale of West vs East, Good vs Evil, freedom vs servitude, is now being rolled out as the region’s energy revolution becomes a matter of geopolitical significance — and a test of allegiance.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.