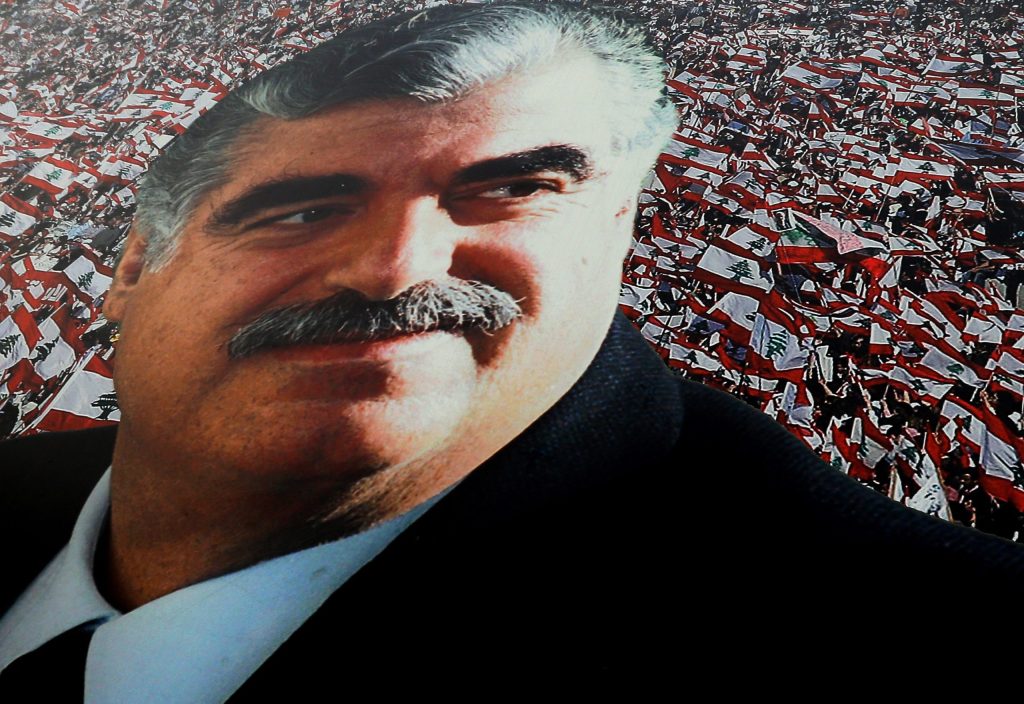

Almost a decade ago, I went to Lebanon to investigate who had killed Prime Minister Rafic Hariri. It was a momentous event in the Middle East, and it changed this tiny, beautiful state forever.

Hariri was killed on Valentine’s Day 2005 alongside 21 others after a bomb exploded as his motorcade drove through central Beirut. Today, 15 years later, the UN-backed Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL), set up in the wake of his death to bring those responsible for it to justice, finally returned its verdict.

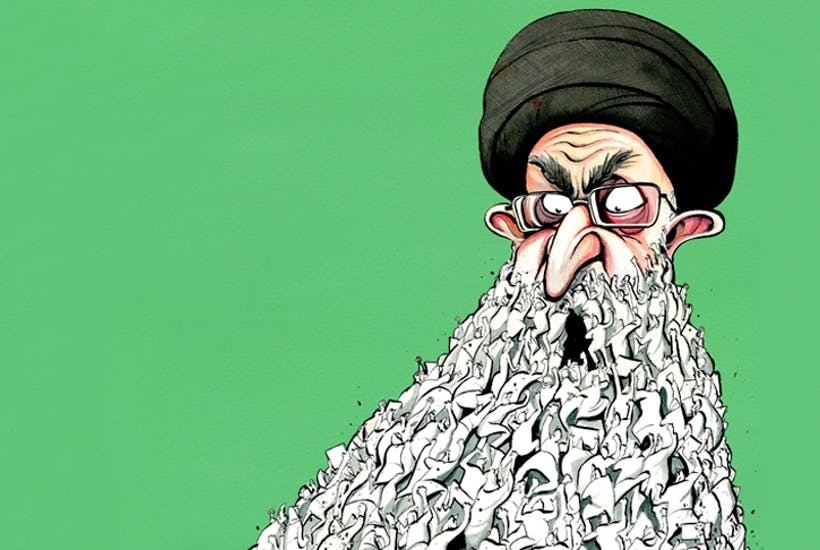

Salim Ayyash, Hussein Hassan Oneissi, Assad Hassan Sabra and Hassan Habib Merhi, all accused of being members of the terror group Hezbollah, have been on trial in absentia since 2014. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has publicly refused to extradite them, and even referred to them as ‘saints’, warning that the tribunal was ‘playing with fire’ while its findings could well ‘ignite an inner conflict’. They remain at large to this day.

In the event, only Ayyash was found guilty — of conspiracy to commit a terrorist act, murdering Hariri, murdering 21 others and attempting to murder 226 more. The others were acquitted. Mustafa Badreddine, the commander of Hezbollah’s military wing, had also been indicted, but was killed in Syria in 2016. Prosecutors had described him as ‘overall controller of the [assassination] operation’.

Much of the case was built around the work of Wissam Eid, a Lebanese intelligence official who analyzed phone networks, logs, and data produced from mobile towers before crunching them into a simple Excel spreadsheet. From these, he was able to map the movements of Ayyash and Badreddine leading up to the assassination. Eid was brilliant and this proved his undoing. He was killed in a suicide car bomb attack in January 2008.

Indicting Badreddine was a big deal. Hezbollah is the de facto ruler of Lebanon. Going after one of its top military commanders sent a message to Hezbollah that, though it might be the power on the ground, it was not untouchable. At least in theory.

The truth is a lot more demoralizing for those hoping to see an end to Hezbollah’s seeming invincibility. As well as acquitting three out of the four accused, the presiding judge David Re also said there was no evidence of Hezbollah or Syrian involvement in the attack.

It’s tough for some Lebanese to swallow. ‘It’s a joke’, a friend in Beirut texted me. The journalist Kareem Shaheen was blunt: ‘Salim Ayyash was responsible for buying the explosives-laden Mitsubishi truck in collaboration with Mustafa Badreddine. Together they coordinated Hariri’s surveillance. And he led the team that assassinated Hariri on Feb 14 2005,’ he tweeted.

Former prime minister and son of Rafic, Saad Hariri, was to the point: ‘we accept the verdict of the tribunal and want justice to be implemented,’ he said. A ‘just punishment’ for those responsible for his father’s death is what he is after. But the suggestion is clear: justice cannot be served while Ayyash remains at large.

While the court ruled there was no evidence that Hezbollah or Syria was involved, Re did say that both had ‘motives to eliminate’ Hariri, arguing that his murder ‘did not happen in a historical or political vacuum’. It wasn’t much but it was something.

Reading the verdict, one of the problems that the court faced was a repeated lack of evidence. ‘No evidence (was presented to us)’ is a striking refrain on the documents; this is, as has been pointed out, very different to ‘no evidence exists’.

[special_offer]

What happens now? Lebanon’s confessional-based body politic remains intractably divided. On one side stands the March 14 Alliance (the date in 2005 when thousands of Lebanese took to the streets of Beirut to demand an end to Syrian occupation). March 14 is led by Rafic Hariri’s son Saad Hariri. Opposing him is the March 8 alliance, which is loosely backed by Iran and Syria, and includes Hezbollah and various Shia and Druze parties. It takes its name from March 8, 2005, the date of the first counter-demonstrations against the so-called ‘cedar revolution’.

The verdict is such that each side will interpret it as they wish. March 14 will point to the conviction of a Hezbollah operative, who clearly would never have carried out such a major operation without permission from higher up, as clear proof of the party’s terrorist nature. March 8 will argue that as the court found no evidence of Hezbollah involvement, the accusations against them since 2005 have been unjust.

Neither side will be happy, and divisions will grow — at a time of acute national crisis when the country needs unity more than ever. And it will be the Lebanese people who pay the price, as they always do.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.