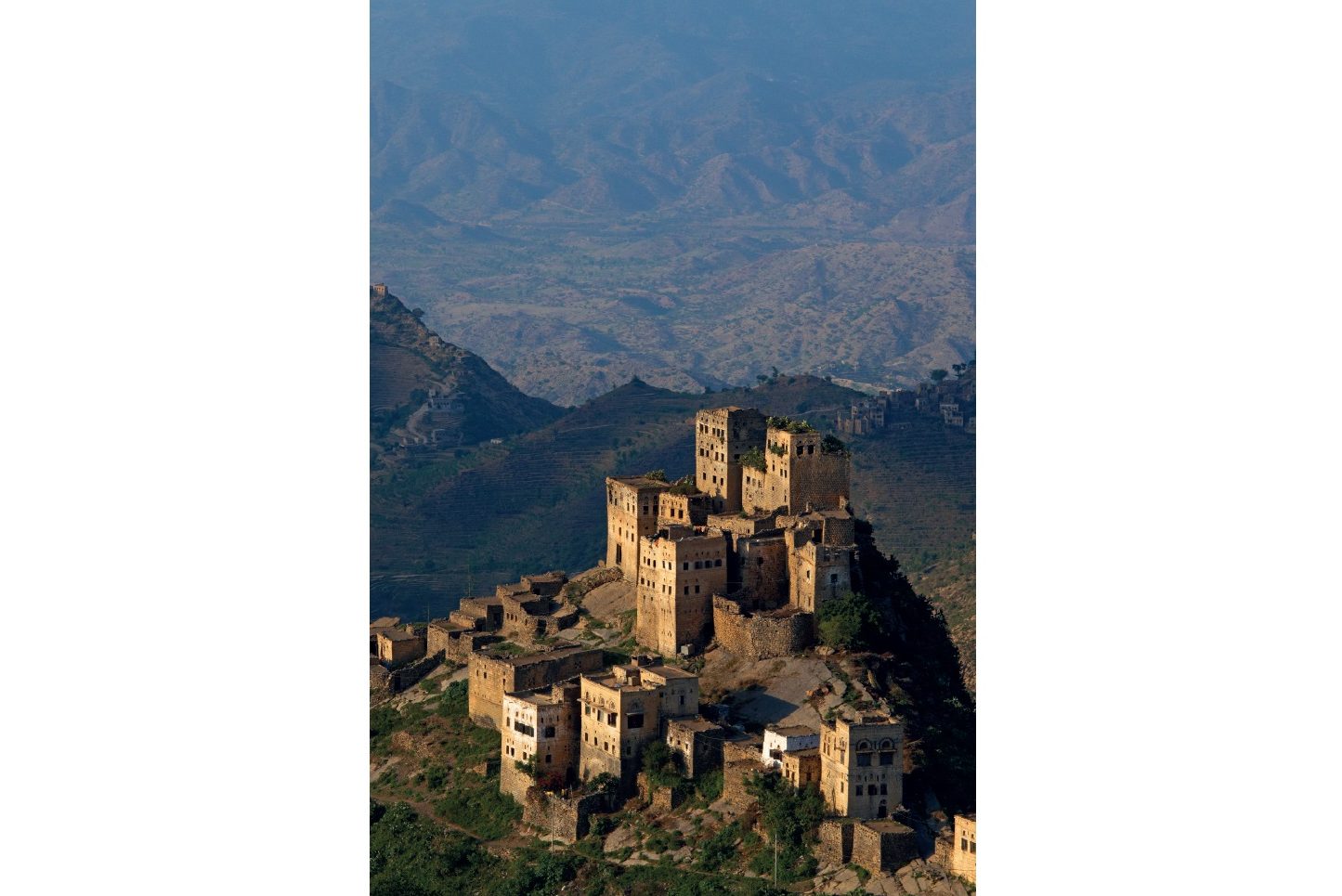

I visited Mycenae for the first time this autumn. While the ruins of classical Athens can seem almost familiar, the ancient hillfort of a millennia earlier truly feels as though it belongs to the world of gods and heroes, of Homer and the Trojan War. If my imagination hadn’t been destroyed by decades of television, I could almost imagine myself there.

One of the curiosities of findings in archaeology and DNA is that many of the old myths appear to be true

Walking past ancient burial mounds and gazing at Argos in the near distance, I liked to think that I was in the footsteps of a real Agamemnon — and perhaps I was, and there really was a king of that name who led a war across the sea. If that sounds fantastic, then one of the curiosities of recent findings in both archaeology and DNA is that many of the old myths we once regarded as fantasy appear to be true (or, at least, true-ish). Mycenae was among the sites excavated by Heinrich Schliemann, the great German businessman, polylinguist, serial liar and classics enthusiast who discovered the city of Troy in 1870. Troy was assumed to be a real place in antiquity and the Middle Ages, but with the early modern period, and the rise of skepticism, it became obvious to educated people that its existence was merely a myth, or a “romance” in Blaise Pascal’s words.

Schliemann thought otherwise and, with the self-confidence of an amateur Victorian adventurer, proved them wrong — although his excavating was so notoriously reckless that he managed to destroy much of the city, as one academic noted dryly, doing as much damage as the Greeks. Schliemann identified the spot in what is now north-west Turkey where a succession of cities had been built on top of each other, and subsequent digs formed a consensus that “Troy VI,” dating from around 1700 to 1300 BC, fits with the historical timeframe of the war. Evidence of Troy has also since come to us from deciphered Hittite cuneiform in Anatolia, which record the existence of a city called “Wilusa,” which historians have identified with (W)ilios, the Greek name for the city of Troy.

The Iliad was composed hundreds of years after the events it describes, although textual analysis suggests that some verses are much older. It would be a stretch to call it history, but even the basic narrative of the Trojan War — excluding the bits about gods arguing about an apple — might be based on more truth than was previously thought.

When I was in sixth form, I remember our classics teacher, a learned and thoughtful elderly woman who even then seemed like a relic from a bygone era of scholarship, telling us that the Trojan War was probably about a trade dispute or similar. The narrative seemed too romantic to rational people. Yet studies of pre-agricultural societies suggest that the kidnapping of women was a very common trigger for war, and it’s not unknown for victims to fall in love with their captors. It’s not implausible that Bronze Age societies would have gone to war over such an outrage.

DNA analysis and modern archaeological techniques have proved oral tradition to be correct many times. At the other end of the continent, recent archaeological finds in Ireland have thrown new light on ancient myths, many written down by monks in the eight century and previously dismissed either as Christian propaganda or sheer fantasy. The most curious involved Newgrange, an ancient mound and burial place in County Meath dating back to around 3000 BC.

These legends recalled that the local king had practiced incest and built a monument to his sister-wife after her death — locals even called it the “Hill of Sin.” This was long regarded as typically Christian prudery, yet recent excavations did indeed show that this ruling elite practiced brother-sister incest, just as the ancient tales claimed. Geneticist Razib Khan wrote of the discovery that “it is intriguing that the early historical Irish had legends of incest at the site of Newgrange, a story that must have survived thousands of years until Christianization and literacy… Is it possible that Irish folklore was able to record an essentially truthful story over so many generations?”

Other traditional Irish myths tell of the short and dark-featured Tuatha De Danann, a supernatural race found in the hills. These may be folk memories of earlier inhabitants who moved to more remote areas when later Bronze Age Celts settled in the valleys, and DNA suggests the shorter, darker people persisted in remote and mountainous parts of Ireland long after the arrival of farmers.

In recent years genetics has also revealed that many ancient national origin stories are essentially truer than thought, as with DNA analysis of the Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain. The consensus when I was growing up was that there had been minimal migration from the continent and that the native people had adopted Germanic norms — the “pots are pots, not people” theory of cultural transmissions. This contradicted the traditional narrative of Gildas, a sixth-century Breton, and Bede, an eight-century Northumbrian monk, who both described large-scale invasion and displacement. Gildas lamented it, Bede celebrated it — both were right. DNA analysis in the last decade shows that Anglo-Saxon migration had been sizable and totally displaced the natives in the east of the country, just as ancient accounts testified.

Some even wackier origin stories contain a grain of truth. One concerns the Lemba people of southern Africa, whose own tradition made the — seemingly bizarre — claim that they were descended from the Jews. Many groups down the years have claimed to be a lost tribe of Israel, yet recent genetic studies indeed reveal the Lemba to be 40-50 percent semitic in origin.

It is possible that oral traditions can pass on half-remembered stories of migration, conflict and disaster. The Norse myth of Ragnarok probably owed something to the extreme weather conditions of the sixth century, the coldest period in recorded European history, when Scandinavians were pushed to the edge of existence.

Perhaps even more intriguing is the Scandinavian folk tradition of trolls, creatures often referred to in tales as “the old ones” and described as uglier versions of humans living in caves. It was the Finnish paleontologist Bjorn Kurten who first suggested that trolls trace their origin to oral traditions relating to Neanderthals, who disappeared as a distinct subspecies 35,000 years ago, but may have survived as relic populations in more inhospitable pockets of the north.

Great cataclysms are likely to be recalled across the generations, and the most famous of these distant disasters is the Biblical Flood of Noah, which tracks many flood myths across Western Asia. Although several possibilities exist, the most popular is the Black Sea deluge which followed a warming climate around 5600 BC, turning that lake into a sea and flooding the region.

This is not the only biblical study that has inspired speculation. In The Book of Genesis, God “rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven” and “the smoke of the country went up as the smoke of a furnace.” Sodom was located by the Dead Sea, so it sparked curiosity when a research team in 2021 presented evidence that a Middle Bronze Age city called Tell el-Hammam, also located by the Dead Sea, had been destroyed by an airburst, created when a comet exploded some two-and-a-half miles up in the sky, causing an impact more powerful than Hiroshima. Christopher Moore, an archaeologist at the University of South Carolina, suggested that the story may have been passed down the generations.

Even the Garden of Eden might have reflected something real. Kyle Harper wrote in The Fate of Rome that between 6250 and 2250 BC the Near East was unusually verdant — even the Sahara was green, while the Near East was “miraculously fertile.” As the climate changed, the former Eden was turned into a desert, and many might have wondered what they had done wrong and concluded that it must have been a woman’s fault.

Archaeology has also shone light on another strange ancient myth — the Amazons. In Ancestral Journeys, Jean Manco noted that some 20 percent of Scythian-Sarmatian graves containing buried weapons belong to women, and many were found just where the Ancient Greeks identified as the

Amazon homeland, near to the river Don in modern Ukraine.

The Sarmatians were a tribe of Steppe horsemen known for their ferocity, who came to be employed by the Romans. More than 5,000 were stationed in the province of Britannia after Marcus Aurelius brought them there in 175 AD. Their descendants, the Ossetians who live on the border of Russia and Georgia, have inherited a curious myth from their forefathers: the story of a dying warrior who requests that his friend throw his sword in a lake to prevent it falling into the hands of his enemies. The friend cannot bear to be rid of such a magnificent weapon and lies twice, only for the hero to somehow know; eventually he flings the weapon into the water, which is caught by a woman’s hand coming out of the lake.

That this strange tale exists nowhere else but among the Ossetians and British suggests that Sarmatians may have brought the legend of King Arthur to Roman Britain, where it survived as an oral tradition for several centuries before being popularized by the medieval historian Geoffrey of Monmouth. Geoffrey’s accounts are implausible — he also claimed that the Welsh came from Troy — and no historian believes there to be much truth in the legend of Arthur. But, well, you never know.