As new technology, AI and the internet take over 21st-century life, I suggest looking to the Amish for guidance. Far from being the Luddites most folk assume, the Amish undertake a guided policy of technological discernment.

When a new practice or device emerges into the world, the elders often gather to test it out over a set period of time. The entire process rests upon this deceptively simple inquiry – “What is this tool for and what does it make us become?” All potential effects on family unity, social cohesion and self-reliance are soon revealed by this one question. Diesel and solar generators pass the test and are often adopted, while social media is largely shunned. Should we be courageous enough to make the same interrogation of social media, I suspect we would reach the same conclusion.

I have adopted the Amish approach to tech and it has been transformative. Alongside my family, I own and manage two restaurants in Kensington, London – La Palombe and Il Portico – both of which have wild game on the menu which I hunt for several mornings a week, often joined by my three children. Unlike the North American model of game conservation, we in the UK are allowed to “market hunt” for wild game, which was effectively outlawed in the US by Teddy Roosevelt and the Lacey Act of 1900.

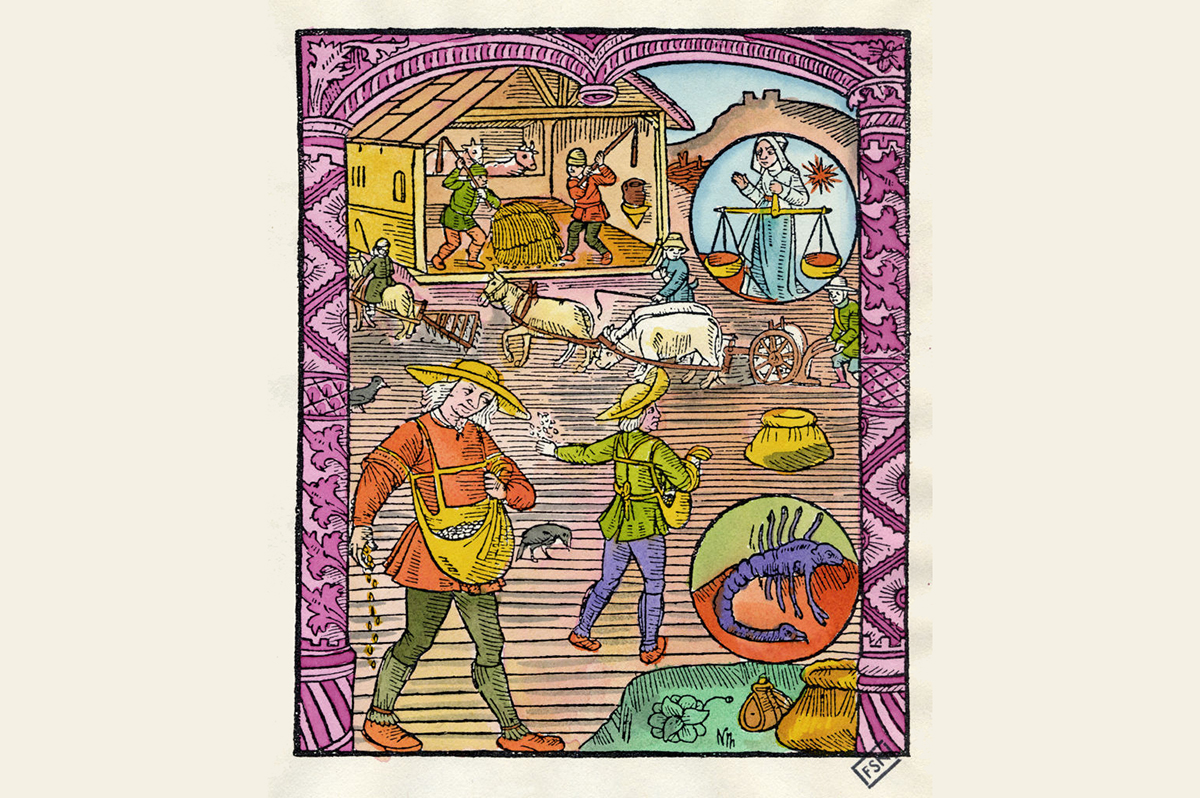

Come the school holidays, my kids get their own chance to trade new tech for old, swapping out their school iPad for an old single-shot rifle or fishing pole as we head to the forest and the sea. These are the tools which have been handed down to us for countless generations. Unlike modern tech, a well-made rifle or fishing rod will become a natural extension of one’s body. The sensation of poise and harmony you feel when using one is in perfect keeping with the surroundings of the woods or the river. A rare and perfect moment of balance.

Those who have been fortunate to have handled an old split-cane fly rod or pre-war Mannlicher rifle will undoubtedly understand. When was the last time you felt in balance holding a phone to your face?

My son has joined me deer hunting for the last two seasons and the effect that spending silent time in the woods has on a boy is remarkable. Since the day he came into this world, my boy has struggled to sleep. He finds it almost impossible to quieten his mind enough to rest. His brain fizzes constantly with questions and prying thoughts. Like all good middle-class parents, my wife and I tried all the holistic practices advocated online. Until, that is, I started taking him hunting. A silent walk in the woods did what all the meditation apps in the world failed at. Turns out that nature has her own way of re-orienting your mind back towards your natural state of grace.

Stuck in a schooling system and world dominated by left-brain thinking, he is constantly taught to acquire information through measurement, deductions and algorithms – no time is spent developing the right hemisphere of his brain to help him find his place in the physical world; to love it and feel at home in it.

Hunting has given my son intuition and insight, and the confidence not to sink under the influence of the technology that makes so many of his peers so unhappy. There is no better way to improve emotional regulation, build resilience, and improve one’s patience than a couple of seasons sat in a high seat, rifle in hand and waiting for a deer to come by. It’s no easy task for an adult let alone a boy, but after a while the results will speak for themselves.

In Europe, the average prisoner spends more time outdoors than your average school-age child. In America, the difference is even more stark, with many reporting only around 30-60 minutes per day outdoors, including commuting time between buildings.

If we are serious about ending our children’s disordered attachments to new tech, then perhaps the answer lies in a little Amish discernment and in picking up again the old tools that served us so well for generations.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply