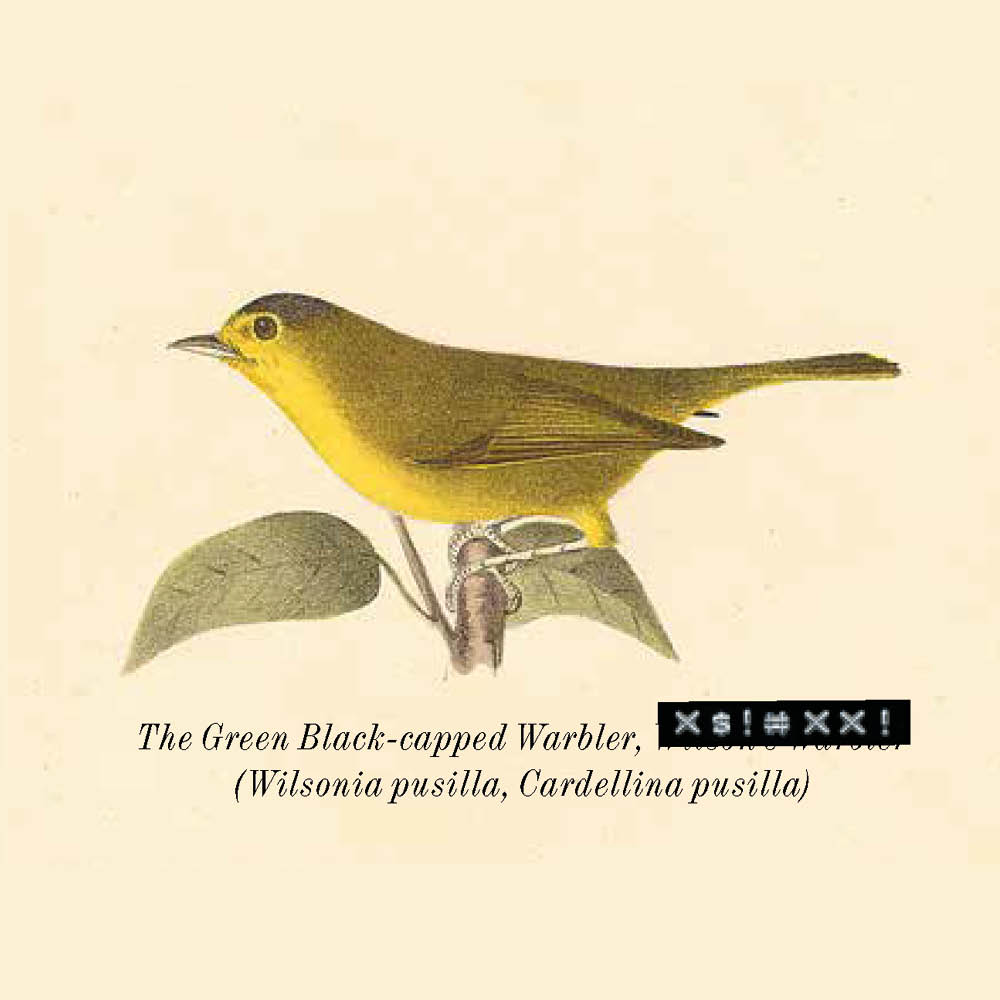

Say you’re easing along a meadow stream, upslope but not steep, somewhere in the Rockies. It’s a morning in spring, the mountains ahead still mostly snowy against a blue sky. A bird sings, giving itself away in a clump of alder. New to birding, you’re naive but full of hope, and through the binoculars you find a thing with feathers, small and olive with yellow breast and black cap. A Wilson’s warbler, says the field guide with its nifty pictures, and you feel the satisfaction of putting a name to a part of the profusion of nature.

You’re out there — need it be said? — for the peace, and the bird, deftly identified, is a totem of tranquility. The matter of naming creatures crops up in the Bible, where it’s the first amusement of humankind, even before the sport and sweat of procreation. Without labels, creation remains somehow still undifferentiated, indefinite.

Alas, such peace isn’t long for this world. You might imagine that American birders and serious ornithologists of the past couple of centuries have been minding their chirpy business, not oppressing anybody. Not so, says the American Ornithological Society. The problem is the pesky names of some eighty species of American birds, among them, prominently, the Wilson’s warbler. Those eighty offenders are eponymous — that is, their names are derived from persons. Nearly all those figures were fervent naturalists who did pioneering scientific work when the continent was mostly a wilderness — but to have drawn a breath back then, if you were of European descent, is retrospectively a crime, as the New York Times now lets us know. Last year the AOS joined the chorus, declaring that the eponyms must go: all eighty will be scrapped. The AOS claims authority over the names of all North American birds, so there we are.

The purge is defended on two immiscible premises. First, that birders of color feel menaced by the noxious names. Second, that nobody knows or cares about the forgettable persons the names belonged to — which pretty much undermines the first.

Farewell, then, to the Baird’s sandpiper, named for Spencer Fullerton Baird, the first curator at the Smithsonian Institution and primary author of the landmark study A History of North American Birds. Adios, Lewis’s woodpecker and Clark’s nutcracker. Yes, that Lewis and Clark, on whose historic expedition Meriwether Lewis described some 300 species of birds, fish, mammals and plants new to science.

Not the sort of person, any of them, the AOS wants on a birdwalk. Their names, says AOS president Colleen Handel, “have associations with the past that continue to be exclusionary and harmful today.” Executive director Judith Scarl concurs: “Exclusionary naming conventions developed in the 1800s, clouded by racism and misogyny, don’t work for us today.”

The AOS membership, it turns out, wasn’t consulted, nor was its committee in charge of the checklist of American Birds, which unanimously opposed the sweeping changes. Most ordinary birders were stunned or sad or pissed off; the revisionists cheered. Birding has become a battleground — far from the broad sunny uplands it was before 2020.

That year, as the George Floyd riots went on, an activist group solicited signatures on a petition to the AOS, urging the removal of eponyms that “commemorate men who participated in a colonial, genocidal and heavily exploitative period of history.” The AOS responded by changing McKown’s longspur, a name in notably bad odor, to “thick-billed longspur” — John P. McKown, who collected the type specimen of the bird in the 1850s, having later been an officer in the Confederate army. (As to “thick-billed;” it’s thick-headed, only dully descriptive of the bird.)

The activist group, Bird Names for Birds, was seeking far more: all eighty eponyms needed to go. BN4B, as they styled themselves, assembled a catalog of the offenses behind the names. There’s the Reverend John Bachman (a sparrow and a warbler), who ministered to slaves but also owned some; and General Winfield Scott (an oriole), who fought for the Union but enforced the removal of Native Americans on the Trail of Tears.

From there, the charges get gauzy. Thomas Nuttall (a woodpecker), guilty of studying the biota of the West, was “part of the myth-making that fueled the ravenous land grabbing of the Manifest Destiny period.” John Townsend (a warbler) obtained an Indian skull for study, and so was a racist — never mind that he wrote about Indians with genuine sympathy. A doctor, he was shocked by the deaths of Indians by disease contracted from whites and lamented that it looked as if “these poor denizens of the forest and the stream should go hence and be seen no more.” BN4B opts not to mention Thomas Say (a phoebe) who traveled widely in Indian territory and in 1818 denounced the “most cruel and inhumane war that our government is unrighteously and unconstitutionally waging against these poor wretches whom we call savages.”

What, then, of Alexander Wilson (the warbler and four other birds), long considered the father of American ornithology? Being the father of anything, no doubt, is already a rap; but BN4B piles on, crowing that Wilson “exploited Indigenous people’s help and knowledge.” Which is to say: he talked to them and they gave him directions. Wilson’s great contribution was his American Ornithology, nine magnificent volumes of his paintings and text, informed by thousands of miles of travel afoot. Ciao, Wilson. Surely he’s guilty of something.

Why not drop just the handful of names that realistically pose a problem, rather than raze the pantheon of American ornithology? “Criteria for identifying which historical figures had done harm would be culturally influenced,” says the AOS. “Any effort to make such judgments” would be “fraught with difficulty and negativity and become an unwelcome public and scientific distraction.”

But the AOS strikes a pose of moral superiority in canceling any names at all. In torching eighty at once, it convicts the whole lot. Hence the predictable headlines: “Dozens of bird names honoring enslavers and racists will be changed” (Washington Post). “Nearly eighty bird species names with racist roots are about to be changed” (CNN web). Science magazine likened the fray to fierce debates elsewhere over “names that honor, for example, the fascist dictators Adolf Hitler or Benito Mussolini.” Let it be noted, in case of doubt, that none of the eighty birds is named for those two raptorial tyrants, nor even for Donald Trump.

To assign new names the AOS will assemble a committee including “experts in communication” and “social scientists” — a reassuring thought. White folks, hints BN4B, whose leadership is white, shouldn’t take part. The new names are to be “descriptive.” Look for a spate of compounds ending in –breasted, –legged, –rumped and the like.

All this may seem a sideshow, but there are an estimated 45 million birders in the US. The AOS aims, by bowdlerizing its bird list, to bring more people of color into birding, thereby growing the constituency for bird conservation. So far it’s mostly divided birders and dragged birding into the culture wars, and that can’t be a help.

“If you really want to get more diverse folks interested in birding,” writes Paul Lehman, an editor at North American Birds, “go into classrooms and give talks or lead walks, or try directly mentoring one, two or three individuals. But wait, that actually takes a lot more time and effort than changing a bird name!”

Stability matters. A granitic set of names, fixed and familiar, is the bedrock of science and birding alike. To change eighty names would, in the words of the disregarded AOS checklist committee, cause “massive instability.” Whole libraries of bird literature — from field guides to scholarly papers to the hefty Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds — would become a hall of broken mirrors.

Kevin Winker, curator of birds at the University of Alaska Museum, compares a stable array of names to infrastructure. “Large-scale changes,” he writes in a paper not yet published, “risk seriously degrading this heavily used linguistic infrastructure.” Discarding a name “simply because it’s an eponym produces an immediate barrier in communication with your contemporaries.”

(As a long-time member of the AOS committee on bird names, Winker opposed the AOS leadership on the idea of the eighty changes. On the announcement that the changes would indeed be made, he resigned from the AOS altogether.)

Since many North American birds migrate to and from the southern hemisphere, changes will affect scientists there who use the AOS names. To them the eponyms seem perfectly sensible. Even today, as new southern species are found, eponyms for the finders are gratefully assigned. The AOS move is seen as arrogant, a new colonialism afflicting global scientists for whom eponyms are easier to use than English descriptive names. “The US would do better,” says Sri Lankan biologist Rohan Pethiyagoda in the journal Megataxa, “to solve its social and political problems rather than renaming them, and especially, rather than exporting them.”

What, in the end, will be accomplished by this virtuous rebranding of American birds? Surely there are better ways to make birding more open and equitable. And is this renaming the end, anyway? If stability counts for so little, then future AOS leadership can dismiss the simple-minded descriptors about to be imposed this year, and retool the nomenclature to suit their own obsessions, whims and prejudices.

We await without eagerness word from the AOS on how many bird genders there might be. Back, meanwhile, to that meadow in springtime, where the Wilson’s warbler doesn’t care what it’s called, its mind not on gender but on juicy insects and sex.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply