I never understood why Plato wrote so harshly about democracy. Was he simply bitter over the death of his beloved mentor Socrates? And could his criticism of direct democracy in ancient Athens apply to a representative democracy like ours? Right now, the United States is looking increasingly Athenian.

Plato characterized the birth of Athenian democracy as a rejection of expertise. The masses, previously content to defer to experts who knew what was good for the city, were led to believe that they could determine the good for themselves — and that the ‘good’ was whatever they subjectively found pleasurable. No longer ashamed to speak up on matters about which they lacked knowledge, the masses bullied the experts into silence and formed a new government and society ruled by public opinion. In democratic Athens, leaders who pandered to the demos were praised and rewarded; those who did not were publicly shamed and ‘canceled’ by exile.

The internet gives us all the illusion of expertise. We read some articles and believe we understand global pandemics. We post pictures to Instagram and voilà, we’re professional photographers. Thinking ourselves capable judges in all matters, we — like the Athenians — feel emboldened to make demands of our leaders. Social media mimics direct democracy, lending everyone a voice in the American agora and a chance to shout down those who disappoint.

Politicians pandering to American public opinion is nothing new: social media ‘likes’ have merely intensified their efforts. But in recent months, just as Plato warned, would be leaders in other aspects of democratic life are being cowed into submission.

In democracy, Plato wrote in Republic, ‘a father accustoms himself to behave like a child and fear his sons, while the son behaves like a father, feeling neither shame nor fear in front of his parents’. Today, a meme jokes that when parents talk to their children about the birds and the bees, the children respond by talking to their parents about the ‘prison-industrial complex’.

High schoolers demanding an ‘anti- racist’ curriculum? Undergraduates demanding that buildings be renamed? Law students demanding that their professor be fired after quoting Patrick Henry? School principals and university presidents capitulating? Plato predicted this, too: ‘A teacher in such a community is afraid of his students and flatters them, while the students despise their teachers or tutors.’

Hot-button topics like immigration policy and gender politics are Athenian old hat. ‘A resident alien or a foreign visitor is made equal to a citizen, and he is their equal,’ wrote Plato. ‘And I almost forgot to mention the extent of the legal equality of men and women and of the freedom in the relations between them.’

By Plato’s standards, America is descending into a state of such extreme liberty that it cannot possibly survive. When rioters and commentators alike justify looting and violence in the name of a broken social contract, Plato begins to look positively prophetic. ‘In the end, as you know, they take no notice of the laws, whether written or unwritten.’

What then? In recent weeks, we entered the next stage in Plato’s account of democracy’s collapse: oligarchy.

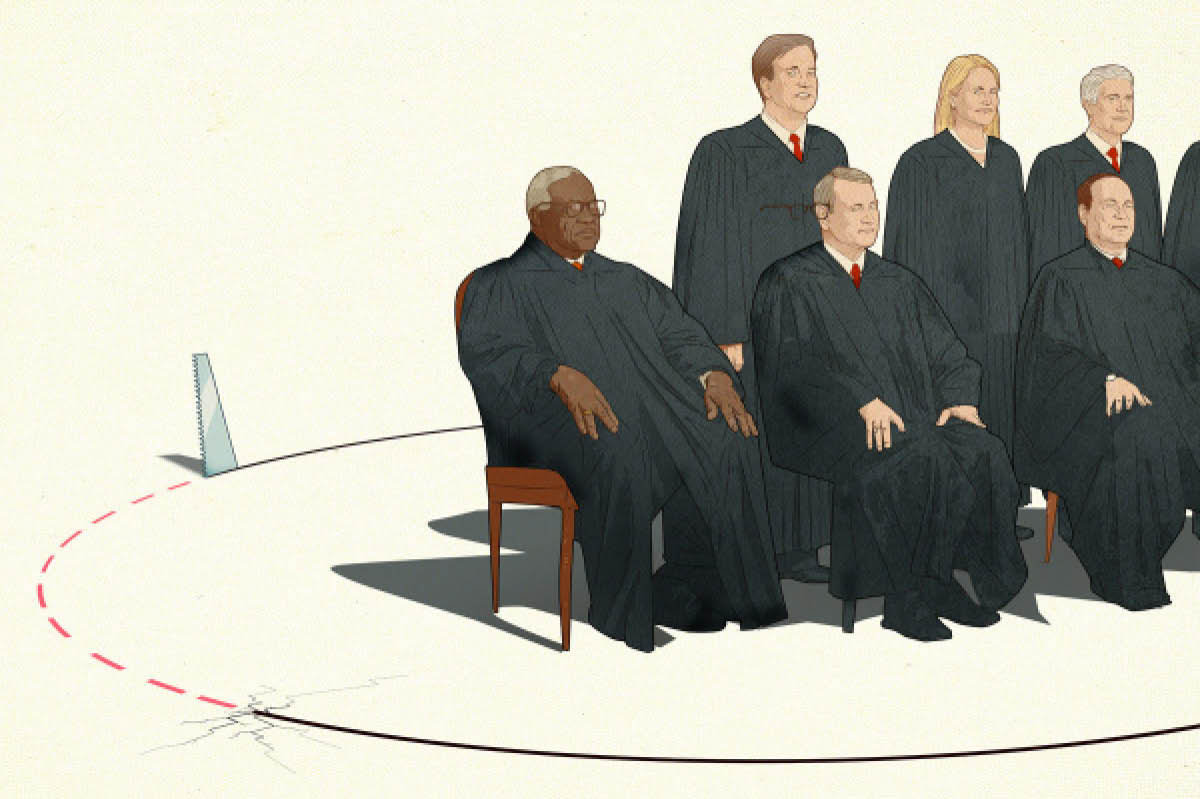

Both left and right have long detected oligarchic tendencies in the Supreme Court. Nine justices, all of whom attended Harvard or Yale Law School, hold the power for life to make many of our biggest decisions. The left calls them oligarchs when those decisions, rooted in the law, oppose the will of the people; the right calls them oligarchs when their decisions, which should, indeed, be rooted in the law, seem instead to be swayed by the will of the people.

Plato says that if you call someone an oligarch enough times, he will eventually become an oligarch. The Roberts Court appears to have taken this to heart. As if trying to restore confidence in the American experiment, Chief Justice Roberts performed a stunning balancing act this summer. First, he handed the mob a 6-3 victory in Bostock v. Clayton County — a policy decision about Title VII that, as Justice Kavanaugh noted, the Court had no business making. Justice Gorsuch’s distortion of the ‘but-for’ test was worthy of the master sophist Dionysodorus, who, in Plato’s Euthydemus, managed to prove that since Ctesippus’s dog is both his dog and the father of puppies, the dog is necessarily his father and the puppies his brothers.

Next, in June Medical Services, LLC v. Russo, Roberts invoked stare decisis in a concurrent opinion that prevents Louisiana from requiring abortionists to have admitting privileges at local hospitals. The Chief Justice had dissented four years ago in the nearly identical Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. Does he really believe that precedent is more important than his oath to uphold the Constitution, and with it his obligation to stop the unchecked slaughter of millions of unborn babies? Perhaps he (justifiably) feared that unless he appeased the baby-killing mob, there would soon be no Constitution left.

Finally, though, Roberts threw the right a bone: the preservation of religious liberty in three cases, protecting believers from the progressive agenda — a calculated (though correct) conclusion to the Court’s coup.

In effect, nine Ivy League aristoi are holding America together. This is not their job, and it should not be. But our elected officials, on both sides of the aisle, are too caught up in pandering and demagoguery to notice.

After oligarchy? Tyranny, says Plato — from extreme liberty to extreme enslavement, via revolution. Indeed, some of my Facebook friends are calling for revolution. (Fortunately, these are privileged New Yorkers who would have to hire people to fight for them.)

From Plato’s perspective, the future regime is already in the works. Every state, he argues, needs a founding myth to give its citizens a shared tradition and purpose. The myth of America 2.0 is the 1619 Project, soon to be taught, as Plato taught in his Academy, at an academy near you.

This article is in The Spectator’s September 2020 US edition.