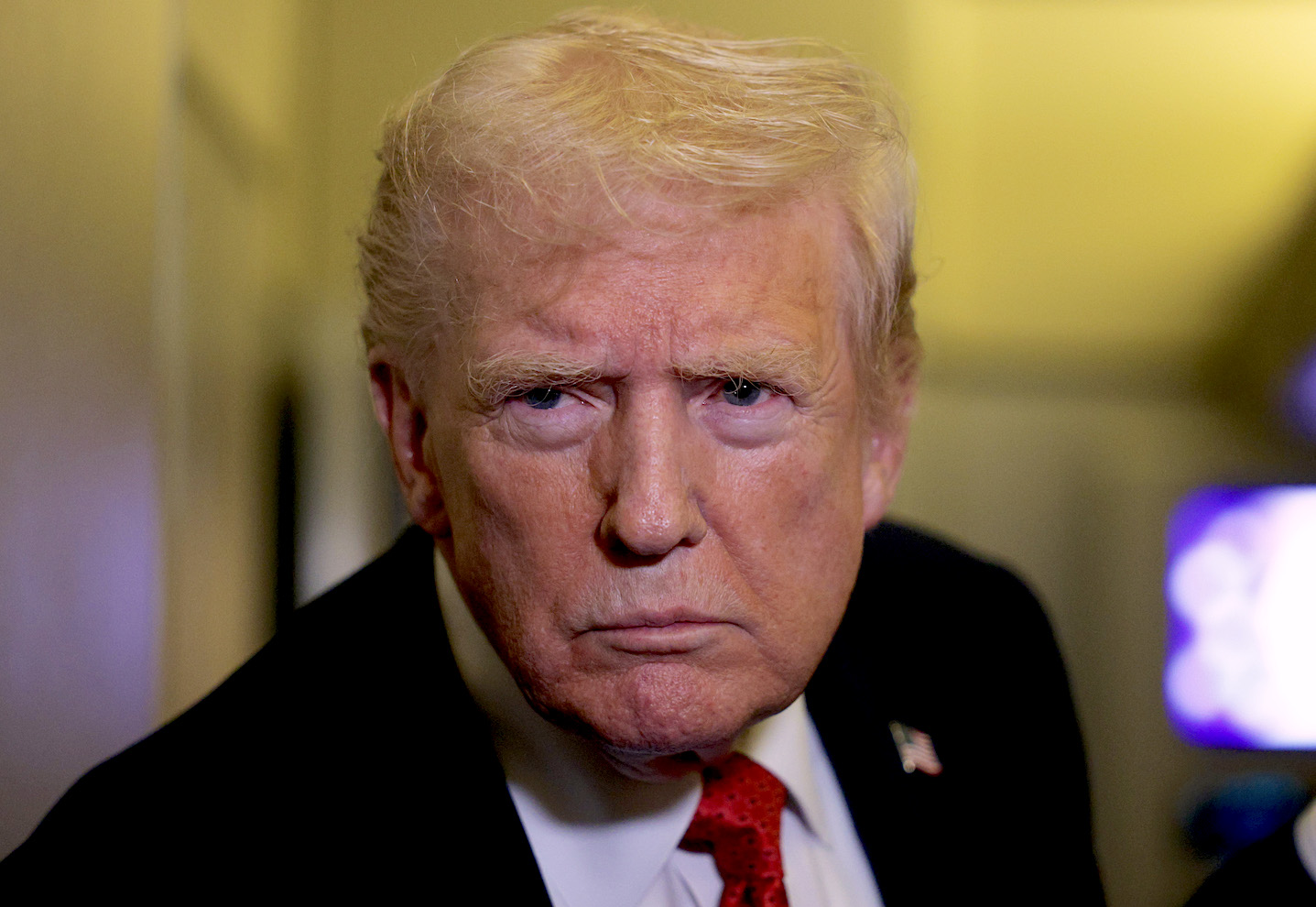

Actions often speak louder than words. And in the case of the US seizing President Nicolás Maduro’s luxury multi-million dollar luxury aircraft this week, that perhaps rings true. The international tip-toeing around how best to respond to Venezuela’s election result — considered fraudulent by many — and the turbulent repression that has ensued, has had global leaders scratching their heads for over a month.

Strongly worded statements condemning the lack of transparency around the election and the antiquated measure of throwing dissenters in jail have fallen on deaf ears. So the taking of the Dassault Falcon 900EX from the Dominican Republic, where it had been stationed since May, was a decisive move by the US — the kind of bold signal many opposition supporters in Venezuela had been waiting for.

For a man incredibly active on social media, Maduro, for his part, has chosen silence

The US alleges that the plane, a kind of Venezuelan equivalent of Air Force One, was initially smuggled out of the US and was in violation of export controls and sanctions laws. The $13 million aircraft was allegedly bought through a Caribbean-based shell company in late 2022 and early 2023. It was then smuggled out of the US to sidestep sanctions, which have been placed on Venezuelan individuals and companies, as well as broad sectors of the economy, in recent years for alleged human rights abuses and corruption. Venezuela’s government has branded the confiscation “piracy.”

“Let this seizure send a clear message,” said Matthew Axelrod, from the Commerce Department. “Aircraft illegally acquired from the United States for the benefit of sanctioned Venezuelan officials cannot just fly off into the sunset.” The confiscation of Maduro’s plane wasn’t just intended to hurt his pockets — it marks a shift in response to the socialist administration, moving from words to actions. It also signals a potential precursor for further measures intended to pile the pressure on Maduro and his friends to step aside. Rumors that the US has already drafted a list of individuals for sanctions are already circling.

Ever since the head of the South American nation was declared winner of the presidential elections for a third term in July, despite pre-election opinion polls predicting his dramatic loss, calls for him to prove his victory have been ringing loudly both from within the country and outside it. The country has plunged into economic chaos in the eleven years that Maduro has been in power, and increased its use of authoritarian measures. Almost 8 million people, a quarter of the population, have left the country. Critics of sectoral sanctions say they have exacerbated Venezuela’s humanitarian and economic crisis.

While evidence of a Maduro win is still absent, the opposition quickly presented evidence in the form of voting tally receipts. These appeared to show its candidate, Edmundo González, had won by a landslide with 67 percent of the vote, compared to Maduro’s 30 percent. The softly spoken, retired diplomat took on the role of opposition candidate after opposition leader María Corina Machado was banned from running. This week, a judge issued an arrest warrant for González, accusing him of a multitude of crimes, including conspiracy and falsifying documents in relation to the election.

The Biden administration had until now responded cautiously to Venezuela’s predicament and refrained from impulsively slapping on more sanctions, like the ones introduced by the Trump and Bush administrations before it. It had in fact temporarily relaxed some sanctions on the oil and gas sector ahead of this year’s vote, but reinstated most of them due to a lack of free and fair conditions for the election. Many analysts have decried the inefficacy of sanctions.

Much of the US and rest of the international community’s hesitancy over responding to Maduro more strongly is borne out of past setbacks. The rejection of the 2018 election result and recognizing Juan Guaidó in 2019 as the interim president of Venezuela by the US and other countries yielded little progress. He was eventually removed from leadership after failing to make significant gains against the Maduro government.

A number of other countries, especially South American ones such as Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, have been more outspoken in their condemnation of the government’s recent fraud and repression. “There are 30 million Venezuelans screaming. Is anyone going to help them, or are they condemned to live in hell?” said Washington Abdalá, Uruguay’s representative at the Organization of American States. Around 2,500 people are thought to have been detained since July 29. During protests, twenty-four people were killed.

Hopes had been pinned on a trio of Latin American presidents from Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. These left-leaning governments, with closer ties to Maduro, have been seen as potential mediators in the move towards a negotiated transition with the opposition. However, they too have made no headway.

For a government that defines itself as pro-wealth redistribution and anti-foreign interference, the plane saga is politically embarrassing for Venezuela. Caracas has remained relatively tight-lipped, apart from a Foreign Ministry statement: “Once again, the authorities of the United States of America are engaged in a criminal practice that cannot be described as anything other than piracy.” It continued that it has the right to “take any legal action to repair this damage to the nation.”

For a man incredibly active on social media, Maduro, for his part, has chosen silence, perhaps not wanting to draw attention to the purchase of his luxury plane, while many of his public sector employees earn just $3.50 a month. While actions often speak louder than words, silence does too.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply