Despite the sharp polarization of American politics, there is surprising agreement on what went wrong with capitalism. Whether the writer or politician is coming at this question from the left or right, the blame often falls on four decades of “small government” ideology and free market orthodoxy since Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Whether the flaw in question is slowing productivity growth, the rise of oligopolies, the export of jobs, or income and wealth inequality, its source is traced to excessive faith in the “magic of the market.” Capitalism’s flaws are “market failures.”

The problem: this narrative is wrong on the facts. Today, as Biden pushes forward plans to restore “big government,” and many Republicans embrace new barriers to trade, capital and immigration, the reality is that government has been expanding in an almost unbroken line, and most every measurable respect, for nearly a century. The flaws of capitalism, in its modern, distorted form, are government failures.

How could standard histories fall so far off the mark? After the anti-government revolution spawned by Reagan, and Margaret Thatcher in Britain, their agenda of cuts in spending, deficits, taxes and regulation often did shape the political conversation in the capitalist world, but it did not downsize any aspect of the state. Consider as one striking example the regulatory state, which dates to the nineteenth century and began to expand in earnest during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

As America prospered after World War Two, economic regulation designed to protect the struggling masses against price or supply disruptions gave way to social regulation, aimed at improving the quality of life for the growing middle classes. Under Richard Nixon in the 1970s, his economic advisor Herb Stein would later recall, “probably more new regulation was imposed on the economy than in any other presidency since the New Deal” — including new rules to protect job safety, clean air and water, marine mammals and more.

By the late Seventies, the tangle of red tape was provoking a backlash from an unexpected alliance: conservatives who hated regulation for distorting market efficiency, and liberals who hated regulation for raising prices and thus hurting the average consumer. Still, rhetoric didn’t produce much action.

The pattern was already set: the regulatory state expands, rarely if ever contracts. A few of the relief agencies created by Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the Depression no longer exist, but often because they were renamed or folded into other agencies. Every new agency develops a circle of supporters — its own staff, clients in the public, backers in Congress — who defend its turf.

Nixon had a plan to streamline twelve government departments into nine, but Congress approved only those parts of the plan that created new agencies: the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Reagan would try to eliminate those two agencies as well as the Department of Energy, created by Carter — and Congress turned him down too.

It’s been said that the government safety net is like plastic wrap — once stretched, it never shrinks back to size. The same can be said of red tape.

The growing bureaucracy spawned a boom in the lawyer population, which was growing by about 30,000 per decade before 1970, and 100,000 per decade since. Dense regulation helps explain why America has more lawyers per capita than any other country — and why the bureaucracy is so expensive.

Spending by US regulators has more than tripled to $70 billion in constant dollars since 1980, and staffing has nearly doubled to 280,000. Reagan did slow this expansion in his early years, but by the end of his second term staffing and funding had regained their old levels.

Though Bill Clinton has often been cast as an anti-government “neoliberal” in the Reagan mold, he did not downsize the regulatory state either. Since the end of Clinton’s first term in 1996, the bureaucracy has issued more than 3,000 new rules virtually every year but one (2019); a chart on the cumulative growth in red tape looks like a set of stairs, climbing upward. Over the same period, the United States has eliminated a total of just twenty rules, according to Clyde Wayne Crews Jr. of the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

Even Donald Trump, who promised “the deconstruction of the administrative state,” and ordered regulators to eliminate two rules for every new one, did not deliver. A flurry of regulations during his final year put his output of new rules on par with his predecessors’. The reality is that “deregulation” has always meant rewriting rules at greater length and complexity, often with more loopholes, not “cutting” red tape.

Meanwhile, the same process of illusory deregulation was underway in Europe. In his 1996 book Freer Markets, More Rules, UC Berkeley political scientist Steven Vogel wrote that the deregulatory revolt was largely a myth, having had little effect in the United States, Japan, Europe, or the United Kingdom. Of the fifteen key British regulatory agencies, he pointed out, twelve were established after 1980, in the midst of the alleged anti-government revolution. In most cases, he wrote, “governments have combined liberalization with re-regulation, the reformulation of old rules and the creation of new ones.” The “big bang” reforms of London finance during the 1980s were, for example, accompanied by the Financial Services Act, which created a web of red tape “more complex and burdensome than what it replaced.”

The subsequent advance of the regulatory state in Europe was clouded by the fact that most Europeans came to live under two governments — one national, one continental. By the late Eighties Europe was moving to create a single market for goods and services, and a new administrative state with what Columbia Law School professor Anu Bradford calls “vast power” to regulate those markets. Since then, this Brussels-based bureaucracy has expanded steadily, adding staff at a pace of 5 percent a year, hiring mainly multilingual technocrats who are true believers in the project of unifying Europe. In a federation of societies that “have structured their economies so as to allocate more rights to the state as opposed to the individual,” the Eurocrats would extend this trust in the state to the creation of a regional government. And in part because the European Union lacks the power to tax and spend directly, its energies have been channeled into the construction of what one scholar called “an almost pure regulatory state.”

This two-headed government creates a lot of confusion. Scholar Thomas Philippon has argued that Europe “of all places” is replacing the United States as “the land of free markets,” based in good part on evidence from an index of regulations kept by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. It tracks nineteen EU member states, and shows that while seventeen of them were more densely regulated than the United States fifteen years ago, now only two of them are. The limitation, as Philippon points out, is that this index tracks only certain national regulations, leaving out other parts of the code that cover everything from taxes to labor rules.

There is plenty of evidence that these national tax and labor rules are getting more onerous in the large European economies. By 2023, more than a quarter of Germany’s medium-sized businesses were considering shutting down or moving abroad, citing “too much red tape and higher taxes.” France had suffered an exodus of millionaires fed up with high taxes, and it had developed a strange bulge in the number of companies with just under fifty employees — the point at which its tough labor regulations kick in.

On other parts of the code, national regulators aren’t streamlining the rules so much as ceding the authority to write them to Brussels. Europe has thus become “the global regulatory hegemon,” writes Bradford.

Though many liberal critics suggest multinational corporations are engaged in “race to the bottom” — meaning havens of thin regulation in shady microstates — Bradford says the race is in the opposite direction. Any multinational that wants to do business in Europe, which is all of them, needs to meet standards set in Brussels, which are determined largely by its strictest, most powerful members — Germany and France. In Euro-jargon, regulations “are harmonizing up” to the strictest national standards, not “harmonizing down” to the loosest.

And the world has little choice but to comply. European rules now shape industry and business the world over, from how honey is made in Brazil to how milk is produced in China and the degree of internet privacy worldwide. Bradford calls this “the Brussels Effect” and applauds it, as proof that Europe remains far more geopolitically “relevant” than its critics suggest. On whether the Eurocracy helps or hurts the economy, however, she says that question “may not even matter” because like it or not, individuals, corporations, and governments “can do little” about it.

That’s part of the problem, however. Polls from Europe to the United States, Britain, Canada and Australia show growing frustration with capitalism, for many reasons, one being that overconfident governments are turning daily life into death by a thousand bureaucratic annoyances. The fact that many of these annoyances now originate in Brussels would likely make non-Europeans even more frustrated, if they were more aware of what’s going on.

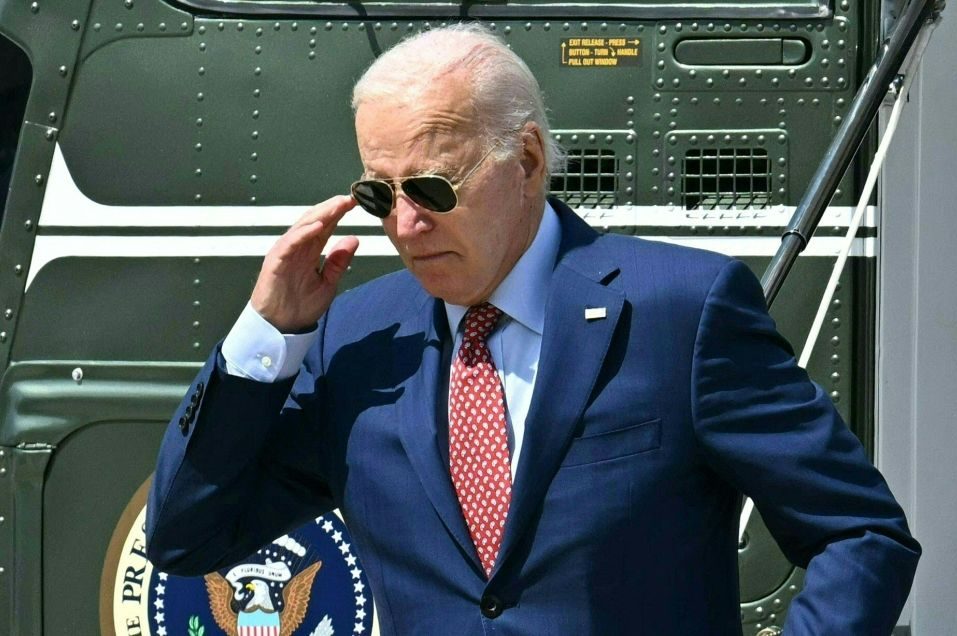

Though this creeping bureaucratization has been underway for decades, Joe Biden has stepped up the pace. Early on he scrapped Trump’s controversial one in-two out order as well as a linchpin of efforts to control costs first established by Carter — the requirement that regulators conduct cost-best analysis before issuing new rules. Instead, Biden directed administrators to avoid “harmful deregulation” and search for opportunities to write regulations “that are likely to yield significant benefits,” even if those benefits “are difficult or impossible to quantify.”

Not surprisingly, the costs of red tape are exploding. In the first two years under Biden, new regulations added an annual average of around $160 billion in costs for impacted businesses as well as state and local governments. That compares to $67 billion a year under George W. Bush, $108 billion under Barack Obama and $16 billion under Trump. In short, while the regulatory state has expanded steadily for decades, its costs have grown dramatically under Joe Biden.

Biden is thus thickening a web of regulation that only the richest corporations and individuals have the resources to navigate successfully. The result is slower, more lopsided growth, benefiting mainly oligopolies and billionaires. The rest experience the unspooling of red tape as frustration, not an opportunity for “regulatory arbitrage,” fueling popular disgust with the capitalist system and undermining trust in the governments that run it. The real story of the last four decades is one of constant state expansion, so the sensible fix for capitalism has to start with less government, not more.

This is an excerpt from Ruchir Sharma’s What Went Wrong With Capitalism (Simon and Schuster).

Leave a Reply