Two articles last weekend made me feel sorry for American young people. We in the anti-woke brigade can be awfully hard on kids. But having been born in the twentieth century turns out to have been a stroke of good fortune.

On Sunday, the New York Times ran a feature about soaring mental illness in American teenagers. Between 2007 and 2018, suicide rates among people aged ten to twenty-four rose by 60 percent. Between 2015 and 2019, prescriptions for antidepressants for teenagers rose 38 percent. Between 2009 and 2019, emergency room visits for self-inflicted injuries among people aged ten to nineteen doubled for both sexes; for girls, they more than doubled.

The journalist proposes multiple explanations: social media, naturally; too little sleep; insufficient social interaction; an earlier onset of puberty. He also blames “the pandemic” for making the situation even worse, though what he should really blame is not a disease that affects young people very little, but lengthy, destructive, epidemiologically ineffectual school closures and lockdowns that affected young people a great deal.

Personally, I’d add further contributing factors. Social media, sure, but more generally a disembodying dependency on the internet that detaches users from not only corporeal people but physical reality itself, which could function as a textbook definition of insanity. (One adolescent subject in the NYT’s piece, “M,” is “in love” with an anime character named charmingly “Genocide Jack.” Yes, romantically in love.) An unhealthy cultural obsession with race and collective guilt (American suicide rates are higher among whites) and pervasive civilizational self-denigration. The contemporary myth that self-knowledge requires seizing on a bespoke sexual or “gender” identity. Accelerating confusion over what it means to be male or female.

For example, out of the blue at thirteen, M demanded to be referred to as “they.” Although it’s opaque just how the third person plural could alleviate their daughter’s chronic anxiety and urge to cut herself, her parents complied. Even the article’s author duly indulges the conceit throughout his text, citing the girl and “their” suffering. If I’d ever insisted on being known forthwith as “they,” my parents might have humored me, but with those taunting little smiles that would have embarrassed me out of the affectation by the end of the week. But then, I was raised by grown-ups.

Otherwise, we may be seeing some overdiagnosis, since these days cultivating a sense of self entails latching on to a problem. For while mental illness is constantly described as “stigmatized,” relentless recent coverage of this topic suggests the opposite: that if there’s not something wrong with you, there’s something wrong with you.

But one more trend is damaging American young people, and it’s crushing. The same weekend, the Wall Street Journal ran a news article headlined: “To get into the Ivy League, ‘extraordinary’ isn’t always enough these days.” This one truly shocked me, and lately I’m hard to surprise.

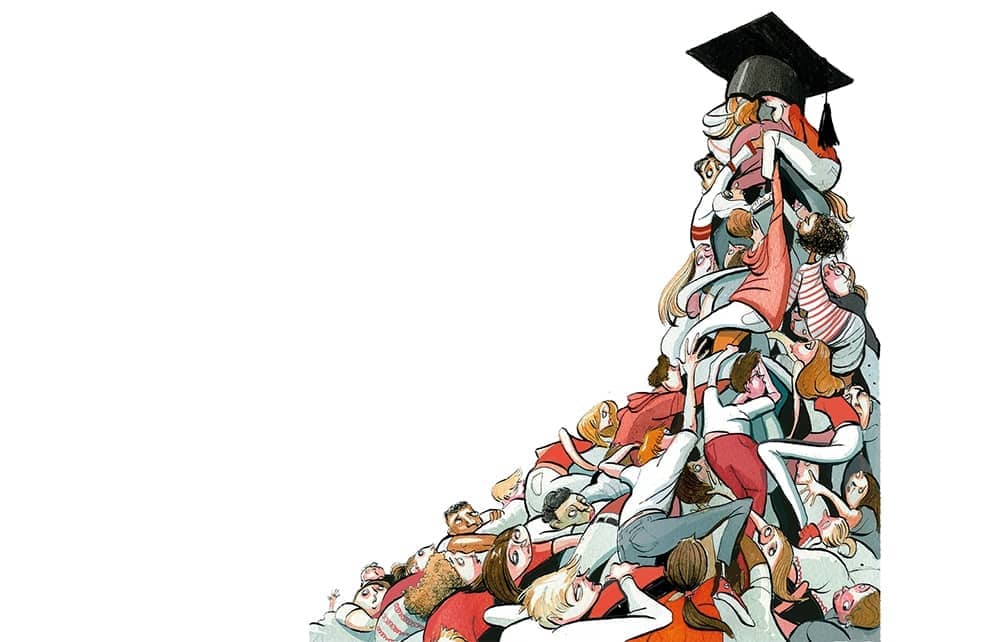

The story led with an eighteen-year-old “star student” from outside Dallas who also suffers from depression and anxiety, as it happens, but whose academic record beats the pants off mine at her age. Kaitlyn has taken eleven advanced-placement courses (that’s a lot), acing all her exams. She got 1,550 on the demanding Scholastic Aptitude Test, nearly a perfect score. Her grade-point average is 3.95 (4 is perfect). Meanwhile she founded the school accounting club, performed in thirty plays, sang in the school choir, helped run a summer camp and had a part-time job.

This girl should be able to write her own ticket, right? “She’s extraordinary,” her guidance counsellor says. “I don’t know what else she could have done.” So she applied to the educational big guns: Stanford, Harvard, Yale, Brown, Cornell, University of Pennsylvania, University of Southern California, University of California, Berkeley and Northwestern.

They all rejected her. But, gosh, I forgot to mention: Kaitlyn is white.

Nearly half of Harvard’s white admissions are athletes or the children of faculty, staff, Harvard graduates or Harvard donors – leaving precious few slots for white kids relying on dumpy old academic pre-eminence. Worse, Kaitlyn is middle-class, and in the US one of the sins of the fathers is success. Ironically, even being female is a disadvantage, because more women apply to college than men, but schools prefer to maintain a 50-50 balance.

This year’s college applicants are further hampered because three-quarters of elite schools have abruptly dropped the mandate for standardized tests like the SAT. Ivy League admissions offices are therefore awash in applications from students with lower scores who’d otherwise have assumed they didn’t have a prayer. Though ignoring test scores is supposedly progressive — in the service of the God of Diversity — the SAT was once a reliable route through which gifted poor and minority students could distinguish themselves. Now the application process is a free-for-all. Thus administrators are at liberty to compose the colors, sexual proclivities, regional make-up and financial circumstances of an incoming class the way earlier Americans once designed quilts.

Planning to attend the less prestigious Arizona State University, which deigned to let her in, Kaitlyn the self-described “perfectionist” is now beating herself up because she blames all those rejections on two Bs (her only Bs) from her sophomore year.

But Kaitlyn’s prospects weren’t crippled by two piddling Bs. Her country has betrayed her. The US is breaking its implicit contract with young people — the promise that if they work hard, follow the rules and out-compete their peers, they will be rewarded. The contrary message reads loud and clear: all that matters is which categories you fall into by accident of birth. Never mind meritocracy; America no longer believes in agency.

I was admitted to an Ivy League university with less impressive scores than Kaitlyn’s. If I had an academic and extracurricular record as dazzling as hers, having for years prioritized studying over hanging out, goofing off and playing video games, and then I was still flatly rejected by my ten first-choice schools, not all of which are even top-tier? Whether or not my mental health was sterling beforehand, I would be demented.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.