There have always been “two Americas.” Our country has always reflected deep social, economic and cultural divides. It’s threaded into the fabric of our national identity, with origins dating back to the very beginning: should America exist on its own? Tensions only intensified in the 19th century between the industrial North and agrarian South, which played out in the Civil War and Reconstruction.

In 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “The Other America” speech described two nations. One was prosperous. The other was trapped in poverty, racial injustice and systemic inequality, especially for black Americans. Decades later, Senator John Edwards revived the phrase with his “Two Americas” speech at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, contrasting the wealthy elite with struggling working-class families.

I was completely unaware of this historical context until I stumbled upon the term on February 4, 2020, after tweeting: “Enjoying the view from ‘One Timeline, Two Americas’ tonight on Twitter dot com.”

After leaving the comfort of my left-wing, ideological bubble to join the culture wars, I was struck by how one event could be perceived in radically different ways. From Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings to the Covington kids’ stand-off, I discovered the divergent lenses through which Americans view their country.

Was it always this way? Was I just oblivious? Growing up in the 1990s, politics seemed less entwined with identity. As a teen I would watch adults debate taxes or abortion – but never in an all-consuming way. The real cultural divides were nerds vs jocks or Nirvana vs Pearl Jam. The punk and grunge scenes of my preteens carried an anti-establishment ethos. Decades on, I watched those rock stars of my youth go all in on defending government overreach during the pandemic.

Yes, there have always been “two Americas.” But the hyper-polarization is a recent phenomenon, tied to social media’s echo chambers, where algorithms feed our biases, amplify division and radicalize us. I shudder thinking about what social media’s impact might have been had it existed on 9/11. It was a catastrophe that united us – even if it was only for a moment. Had we been tweeting, would we have still come together?

Over the past ten years, straddling the worlds of culture-war correspondent, comedian and suburban mom, I’ve observed a new divide: the chasm between the Very Online and the normies.

Nowhere is this gap more apparent than when I’m on stage telling jokes in front of a room filled with tourists. I can now tell immediately who is immersed in digital discourse, and who isn’t.

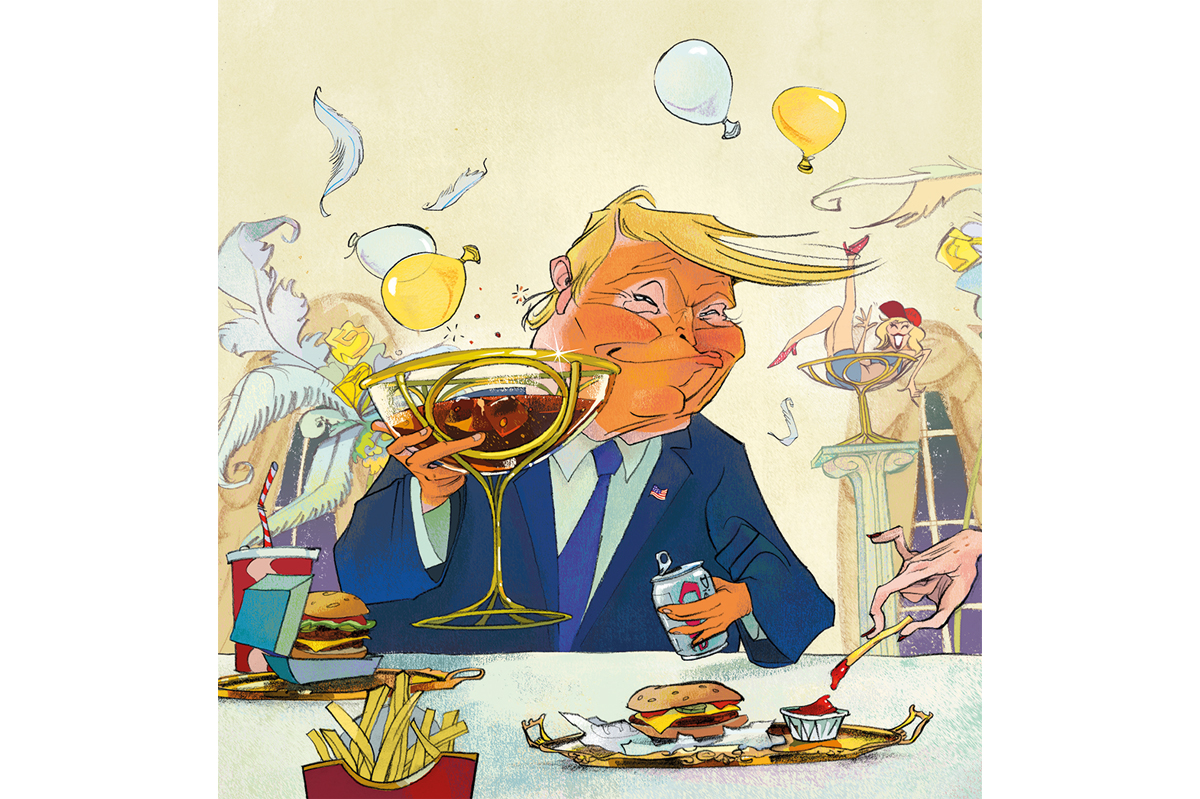

Everything is political nowadays. What beer you drink, what car you drive, whether you wear a mask

I once tried a joke about the term “geriatric mom” being replaced with “geriatric birthing person” – a nod to the shifting medical lexicon I’d experienced in my virtual birthing class. I thought for sure the term was in the mainstream. After dozens of performances met with blank stares and crickets, I realized most normies had no clue what “birthing person” meant, despite my Very Online followers laughing at the joke for years. I abandoned it.

I’ve tried to do some of my Bryan Johnson jokes: he’s the entrepreneur and biohacker known for founding Braintree and is the leader of the “Don’t Die” movement. Online, it feels like you can’t escape him; he’s on X in everyone’s mentions telling them to go to bed. But despite his starring in a Netflix documentary and appearing on the latest series of The Kardashians, normies have no idea who he is. If they do, they just barely recognize him by his face.

On my satirical show, Dumpster Fire, where I cover the culture wars, we often discard topics for being “too inside-baseball.” Recently I wanted to cover my fellow Spectator columnist’s debate, when Douglas Murray took on libertarian pundit Dave Smith on The Joe Rogan Experience. But it was hard to find a way in. The episode sparked countless discussions online – yet most US normies have only heard of Rogan in passing.

Being Very Online distorts reality. It makes niche internet feuds feel momentous. The loudest voices, and the memes they share, appear to represent society. X might not be representative, but it is influential.

It’s where everyone goes to haggle: the virtual marketplace of ideas. But it also disconnects people from the offline America, where tangible concerns such as jobs or family dominate the conversation.

The divide is, in part, generational. Millennials and Gen Z – digital natives fluent in internet culture – dominate Very Online spaces, while older normies gravitate toward traditional media. Just like in real life, online subcultures develop unique languages through slang, memes and shorthand that reflect their values and humor.

TikTok slang is constantly evolving, a way to signal you’re in-group and cool. It makes its way offline, where it sounds like an alien language.

Andrew Breitbart said, “Politics is downstream of culture.” I’d posit that mainstream culture IRL lags about five years behind online America. Many of the same topics are being discussed online and off: war, disaster, tariffs, inflation and just plain old gripes. Still, the worlds have never felt further apart.

It does not help that everything is political nowadays. Everything. What beer you drink, what car you drive, whether or not you wear a mask and how you feel about Ukraine – it’s all just an extension of your identity. Ukraine flag in bio or hanging in front of your home. Black square on your Instagram page or BLM sign on your front lawn. It’s the point in the Venn diagrams where the online and the offline meet.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply