In the precarious world economy of 2023, everyone is selling you something — and much of that something doesn’t amount to anything. Companies, of course, sell you products and services; much of their junk amounts to solutions for problems that didn’t previously exist, though at least there’s still some sort of deliverable. Meanwhile, in worlds as essential to human flourishing as personal finance and bodily fitness, an ever-expanding class of so-called “influencers” are selling a whole lot of nothing dressed up as something. Their underlying success, ostensibly tied to their ability to help people become richer or fitter, depends in actuality on their ability to sell advice or investment opportunities that are likely only to enrich themselves.

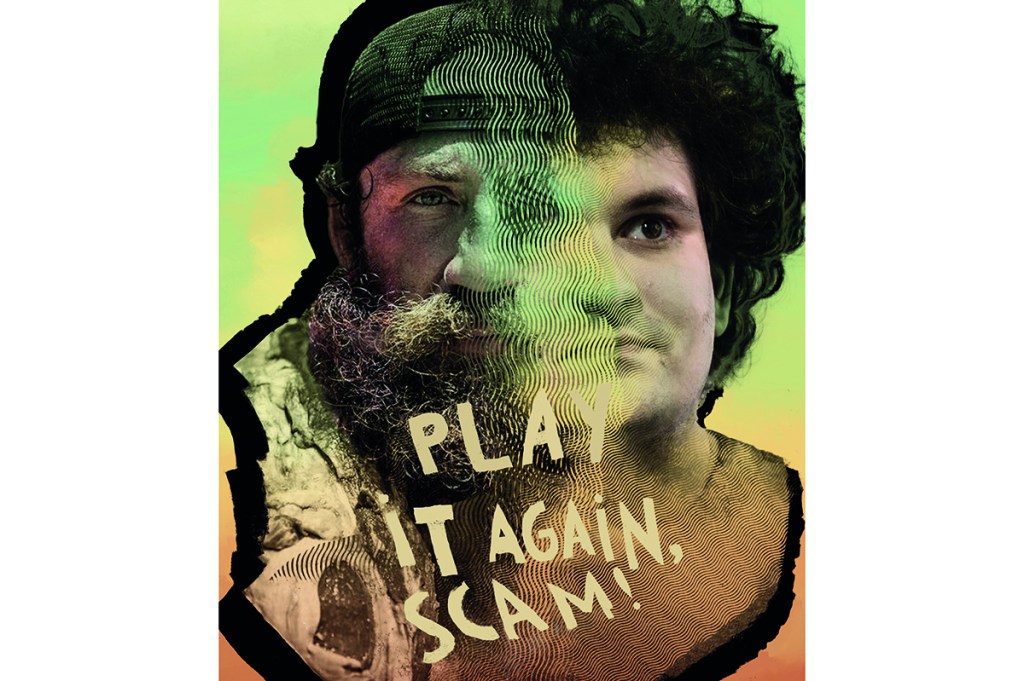

How did this happen? How did pure scam culture — previously the domain of more easily identified “diddlers” and “confidence men” from the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries respectively — give way to ubiquitous, scamming-as-lifestyle “hustling?” This culture is on display in the downfall of fitness celebrity and offal-eater Brian “Liver King” Johnson, and the tribulations of (former) cryptocurrency mogul and (former) billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried. Johnson promised fitness salvation through the adoption of “ancestral tenets” like eating raw organ meats and taking cold baths; SBF’s FTX cryptocurrency exchange subsidized seemingly selfless “effective altruism” and center-left political lobbying. They were both on the make.

The Liver King, a muscular, wild-bearded homunculus, turned out to owe his physique to a designer-steroid regimen rather than his caveman ways, while the wildly-coiffed Bankman-Fried’s empire was underwritten by wire fraud, money-laundering and the gullibility and confusion of FTX customers. When exposed, the Liver King pleaded for clemency on account of his mental health: he needed steroids because he was a depressed middle-aged man. Bankman-Fried confessed that his ethical posturing was a “dumb game we woke westerners play where we say all the right shibboleths so everyone likes us.”

These are but two examples of the innumerable players in the hustle war of all against all, in which the goal, to paraphrase the voluble former NFL running back Marshawn Lynch, is to “get yours more than you get got.” Various reasons could be cited for the successes, temporary though they might have been, of the Liver King and Bankman-Fried; these have to do with the specifics of their different business models, their market research and so forth. However, after nearly two decades spent investigating and researching hustlers — primarily in the “fitness space” — I am much more interested in what they have in common.

As far as I can tell, two time-tested truths connect the confidence men of past and present. Writing more than eighty years ago, University of Louisville linguistics professor David Maurer drew upon a wealth of underworld contacts to try to determine what connected grifters and their “marks,” the people they are scamming. In The Big Con (1940), Maurer explained that the marks — who are sold on get-rich schemes involving bogus stock tips, fixed fights and so on — are somehow waiting to be scammed. Whether people have a little money or a lot, they are united by a singular desire: they have “larceny in their veins,” in the words of the con men who part these fools from their money — they are themselves fundamentally dishonest. Their willingness to be scammed, Maurer wrote, “flares from simple latent dishonesty to an all-consuming lust” to get something for nothing, even as they think of themselves as honest and are indeed repeatedly invited by the con men to repeat their bona fides. Some marks, Maurer further observed, end up fleeced multiple times throughout their lives, always thinking they will beat the next hustle. Some will, in fact, tell the men conning them that they have been conned by every trick in the book, but are persuaded this one is on the level, and will work out for them.

Even more interesting — particularly when one tries to understand the downfalls of the Liver King, Bankman-Fried, Ponzi crook Bernie Madoff and others before them — Maurer discovered that most top con men are themselves highly susceptible to being conned. An expert gambler will take his gambling winnings and invest them in another con man’s stock operation; an expert stock swindler will lose everything he has earned in rigged games of chance, confident that he has developed the perfect system for beating the odds (and the evens).

Today, opportunities to hustle are seemingly infinite: social media influence can drive people to fitness and cryptocurrency scams en masse, as these marks, every bit as larcenous as their predecessors, can now combine dishonest, easy gains in fitness, wealth or status with positions in some ersatz community. This is particularly true of the cryptocurrency world, with its chat rooms and servers full of people urging each other to “hang on for dear life” to some worthless NFT asset because “we are all going to make it.”

Of course, this is deliberately bad advice; you will never profit during the initial sell-off of whatever procedurally generated ape jpeg is about to decline to nothing if you “hang on for dear life.” But most suckers have to bite the dust to make a few top-dog hustlers rich. The Liver King, for example, needed to sell hundreds of thousands of dollars per month of relatively generic protein powders and worthless vitamin pills to finance the five-figure steroid habit that actually worked; it was his marks’ belief in him and his little steroid body, superficially “ripped” due to his drug regimen, that fueled his high sales figures, which he exaggerated in turn to convince more people that they, too, should be buying his wares.

On that note, it cannot be overemphasized that lying is the oldest and most effective performance enhancer of all; it represents the beating heart of all this hustling. Influence is about the projection of a curated self, and behind the curated self is marketing-driven manipulation of our identities. Social media has driven all of us, hustlers in spirit if nothing else, to think of our curated selves in terms borrowed from sales and marketing, the lingua franca of this benighted age. This is the river in which we sink or swim. When you become accustomed to encountering a fair degree of lying in everyday life, you find yourself expecting it from others — yet also, curiously, falling for it whenever you think you’ve found an honest guru.

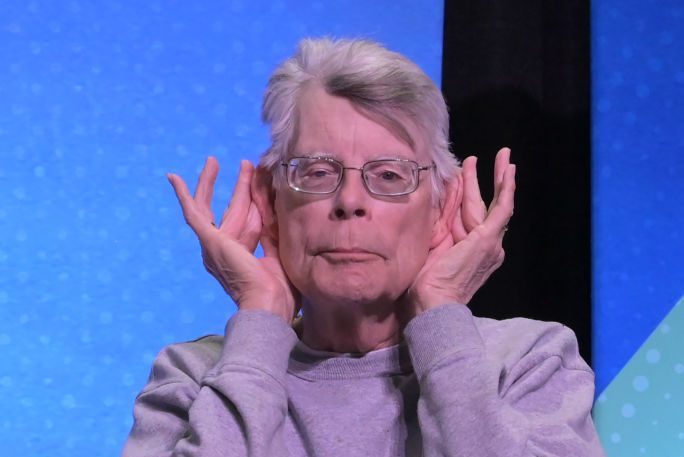

An example from my own research is illustrative here. With my sometime co-author Ian Douglass, I spent over a year investigating a well-known celebrity doctor who had claimed responsibility for the transformed physiques of a number of actors, including Chris Pratt and Christian Bale, who have recently played big-screen superheroes. In the course of our research, we found that everything about this doctor was distorted, exaggerated or outright false. He claimed to have been an All-American wrestler in college; he had in fact wrestled only one match his freshman year. He claimed to have a degree in nutrition from a top school; he had a degree in political science, the registrar confirmed. His website biography contained a list of bodybuilding competitions in which he had won or placed highly; every single one of them was inaccurate. Most galling of all, his claimed PhD, visible in the background of his office photos, was from a diploma mill.

In this case, the good doctor — the kind of person you find when you shake the trees in the groves of the fitness industry — hadn’t merely lied, he had executed a cycle of lies, similar to how he might have put together the “steroid cycles” he had claimed to be expert about. (Alas, steroid cycles, much hyped in bodybuilding magazines in the late 1990s, were also either exaggerated, dangerous or priced out of the range but all but Jeff Bezos-grade moguls.) The legendary wrestling manager Jim Cornette once said, apropos of wrestling fakery, that “you tell the truth at points A and B so you can swerve the marks at point C.” The claims of amateur wrestling glory were a fine example of this; the celebrity “doctor” did wrestle a single match for the college team, so why couldn’t he claim to have been an All-American? He was closer to such a lofty status than someone who never wrestled in college at all.

My father, a franchise car dealer, used to tell my younger self that “selling how to sell” was the easiest racket, particularly in a deindustrialized world where “we no longer made anything.” “You mean to tell me you made all this money just from your selling methods?” he’d joke, adding, by way of reply to his own question, “Yes, I made all this money just by selling you my methods.”

In 2023, the hustlers are everywhere, their language permeates everything and their ubiquity raises the most pressing economic question of all: what’s left?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.