Not one American in a hundred has read Roe v. Wade, and perhaps no more of us really understand how a Supreme Court majority of seven justices barred — or, if you prefer, relieved — everyone else from coming to political terms on abortion. Think of Roe as a dispensation from the fraught business of democratic decision-making. It appears that respite is now nearing an end.

Europe has set the example. It’s where the US seems headed — into years of political fights in one jurisdiction after another, but in states rather than countries. Only with time has most of Europe managed to settle into norms usually established by legislatures reaching compromise aside from any creed, whether that of the Catholic Church or Planned Parenthood.

Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Denmark — what do these countries have in common? They limit abortion on demand to fifteen weeks’ gestation or earlier, albeit with exceptions, some stinting, some elastic. Yes, fifteen weeks is the restriction in the Mississippi law, excepting a “medical emergency” or a “severe fetal abnormality,” which is currently before the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson.

In Europe, limitations as to when abortion becomes illegal generally range from ten weeks (Portugal) to eighteen weeks (Sweden). Among large countries, Poland is alone in banning abortion save few exceptions such as to protect the life of the woman. Britain and the Netherlands are alone in having abortion regimes comparable to what prevails in America, where under Roe restrictions aren’t imposed until approximately twenty-four weeks.

So Europe, after turbulent years and trade-offs, has reached something like a middle way, though one still prone to change in one country or another. Where’s the middle in America?

In six separate polls from 1996 to 2018, Gallup found majorities supporting a general right to abortion in the first trimester and opposing that right in the second. Yet over that same period, Gallup also found — incongruously — support for mandating the states to keep second-trimester abortion legal — that is, support for Roe.

The confusion is hardly surprising. Roe has become older than the median age of the population, and what Roe is alleged to say appears more often on protest placards than in law reviews. Pollsters, in any event, are hardly needed to see that much of America, like Europe, would likely to try to find its way to something in the middle, albeit with certain states — e.g. New York and Georgia — to one side or the other.

Most people trying to hold a job, prod the kids to do their homework, and get the yard work done on weekends don’t devote their days to pondering when personhood emerges during pregnancy. Nor do they indulge in legalistic logic-chopping. But they do think hard with their gut.

To withhold judgment on many abortions, a lot of these people don’t need to know that the decision to terminate a pregnancy is made by hundreds of thousands of women in this country every year. But neither do they need to know the details of the scientific debate over fetal pain to understand that, somewhere in the second trimester, that face in the sonogram looks something like a baby picture. Surely in many states it is these people, the swing opinion on abortion, who could live with a middle way if their perspective survives the current turbulence.

Beyond broad restrictions, every detail could be a point of contention (and arguably should be if it is getting enough attention): waiting periods, parental consent, exemptions to gestational limits. Here’s an instance. Five years ago, a bill introduced in the Pennsylvania legislature, the prime sponsors of the bill being women, included language to ban abortion after twenty weeks. There was no exception for fetal abnormalities. Anencephaly is the failure of the brain and skull to develop, sometimes not apparent until twenty weeks or later. Death is certain shortly after birth if not in the womb. The woman may well need time to decide how to respond to such a disaster. It confronts something like fifteen Pennsylvania women annually.

Good or bad, this bill. What say you?

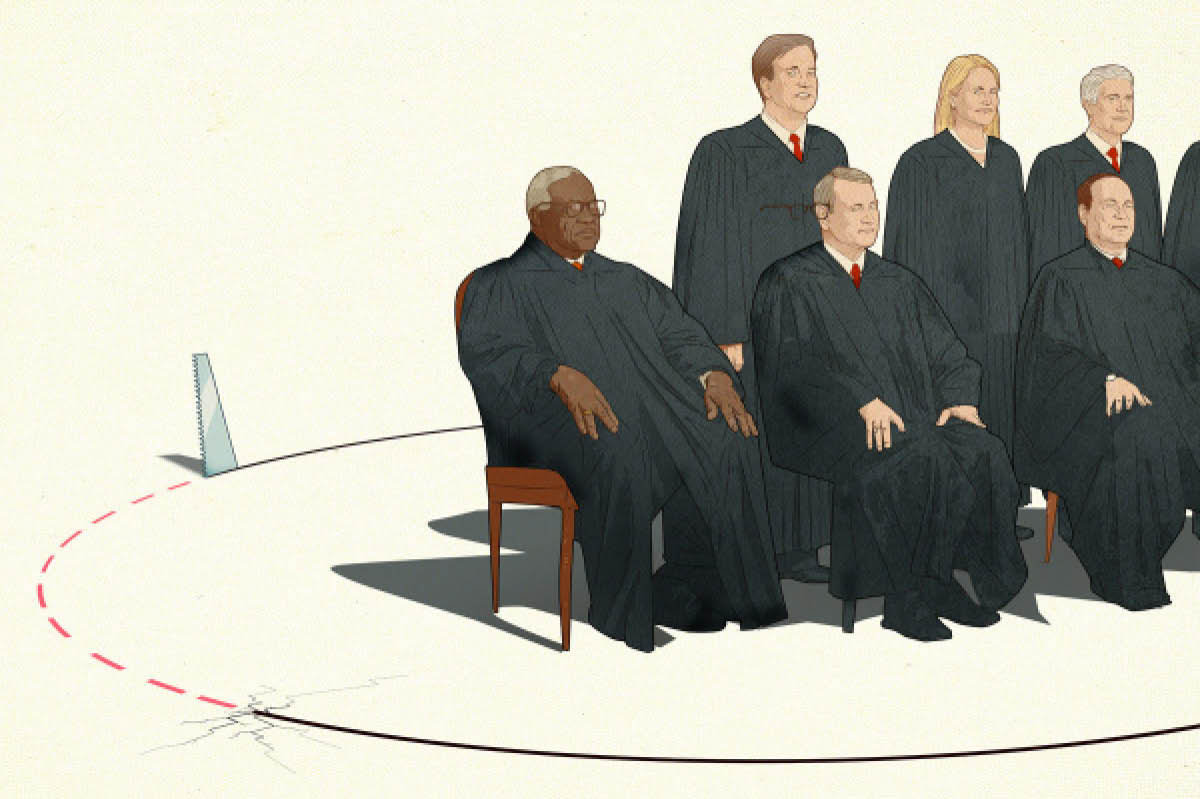

It hardly matters — rather, it hardly mattered then. Seven men in black robes had long since determined that such legislation wouldn’t survive judicial review. Now, those men are dead, as soon may be their holding.

The late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, before she joined the Supreme Court, remarked that a less sweeping measure than Roe “might have served to reduce rather than to fuel controversy” with regard to abortion law. Maybe. We are about to see how much more controversy lies ahead if the court now chooses to step aside.