“Who will guard the guardians?” That question, posed two millennia ago by the Roman poet, Juvenal, is just as relevant today. It recurs every time we learn of a new political scandal – or suspect one is being hidden from us.

There are three such scandals today, and the public has very little confidence in the guardians who will probe them:

- Jeffrey Epstein’s “list” of sexual predators, which we are now told doesn’t exist;

- John Brennan and James Comey’s role in knowingly using false information to prevent Donald Trump’s election in 2016; and

- Joe Biden’s mental decline in office, which his closest aides sought to hide throughout his presidency

Different as these scandals are, they share two overriding traits. First, they directly implicate the guardians themselves. Senior government officials were involved in covering up serious crimes and malfeasance, or, in the Epstein case, possibly were. Second, the public has no confidence that we will ever learn the truth. Trust in government is very low and made still worse by partisan divisions.

Take the Epstein “list.” It was widely discussed during the first Trump presidency and then during Biden’s, as was Epstein’s death in federal custody in 2019. His partner in crime, Ghislaine Maxwell, is now serving a 20-year sentence for her role procuring underage sex partners for Epstein and his friends. Beyond obtaining those convictions, the Departments of Justice of two administrations failed to answer the obvious questions about who else was involved and whether Epstein grew rich by extortion. Their message was essentially, “There’s nothing more to see here.”

The public doesn’t believe them – and for good reasons. Aside from wondering if Epstein really killed himself in jail, they wonder who flew with him to his private Caribbean island, his ranch in the Southwest, and his home in Palm Beach. They wondered, too, how Epstein had gotten so rich, and they suspected the answer was blackmail. When the Department of Justice in two administrations failed to name the others involved or the sources of Epstein’s wealth, skeptics concluded that the answers were hidden because of political corruption. They figured Epstein’s “friends,” a collection of rich, well-connected businessmen, were behind the cover-up.

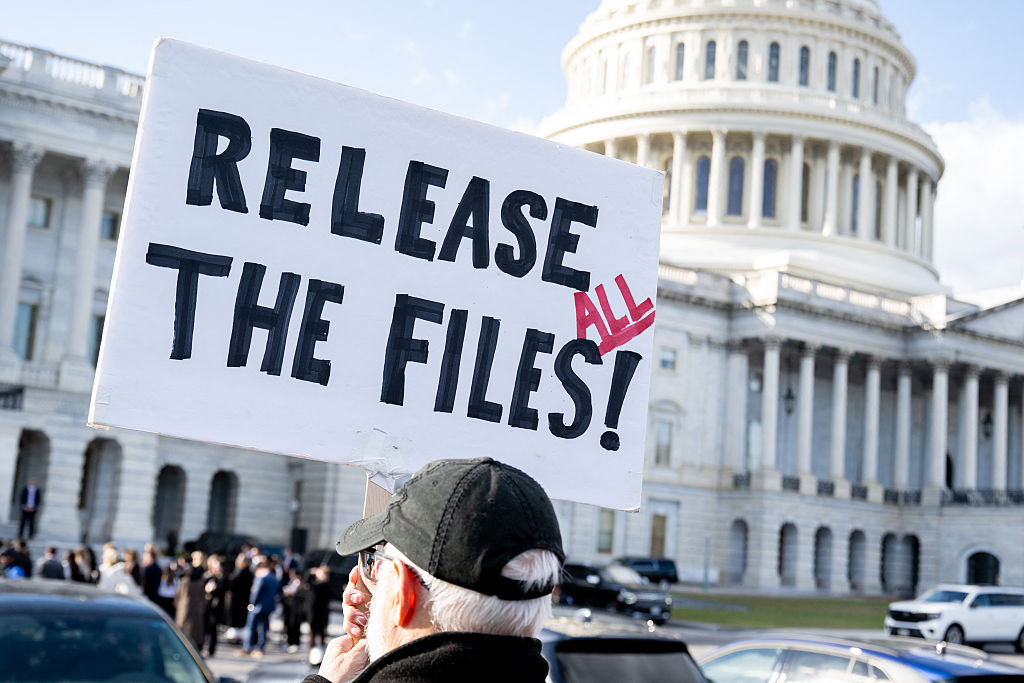

The second Trump administration, fueled by populist distrust of entrenched wealth and power, promised to change all that, to name names, after taking care to protect the identities of all underage victims. Fox News posed the question directly to Attorney General Pam Bondi in February. Had she seen the “Epstein List” and when would she release it? Her response was that the information would be released soon and that the document was “sitting on my desk for review.”

That’s not what happened. What happened was months of delay. Finally, in early July, Bondi was again asked when she would release the list. This time, however, she said there is no Epstein client list. It doesn’t exist.

Was she right the first time or was she right now? Who the hell knows? The point is that very few people simply trust Bondi’s answer, especially after she reassured the public that she had the documents on her desk. Whether or not a formal “Epstein list” exists, we certainly know his private jet carried lots of men to his palatial homes; we know those homes were used as sex dens, with cameras recording the acts in every room; we know the victims were underage girls; and we know Epstein became very rich with no obvious sources of that income. So, what gives?

The disbelief in Bondi’s latest answer reflects a far more serious problem, one that goes far beyond Jeffrey Epstein, beyond one scandal, beyond one Attorney General, and beyond one administration. It reflects a substantial decline in public trust in government, which began in the late 1960s during the Vietnam War (remember when Lyndon Johnson justified his major escalation on what we now know was a false report of North Vietnam attacking a US naval vessel in the Gulf of Tonkin). Then came Watergate.

Those events may have begun the sharp decline in public trust, but it has continued apace. Remember Biden’s Secretary of Homeland Security telling us the border was closed and secure, even as millions of illegal immigrants poured across, unobstructed?

Decades of false statements like that have had a predictable effect. Trust in government now approaches the level accorded used car dealers. In the 1950s, by contrast, more than 70 percent of voters trusted the government. They may have been too credulous. Now, we’re stuck at the other extreme.

Today’s mistrust poses a grave problem for democratic self-government. After all, we have little choice but to rely on government officials for some information, such as whether the bombs dropped on Iranian nuclear facilities were effective. President Trump immediately announced those facilities had been “obliterated” well before any careful assessment could be made. After his comments, his cabinet had to follow the official line. In fact, we won’t know for several weeks and, even then, may not know for sure.

On many issues, we have no direct ways of knowing whether senior government officials are telling us the truth. Now, we suspect the answers are more self-serving than truthful. The problem is compounded by pervasive distrust of the media, where partisan advocacy has corrupted what was once neutral, hard-news reporting.

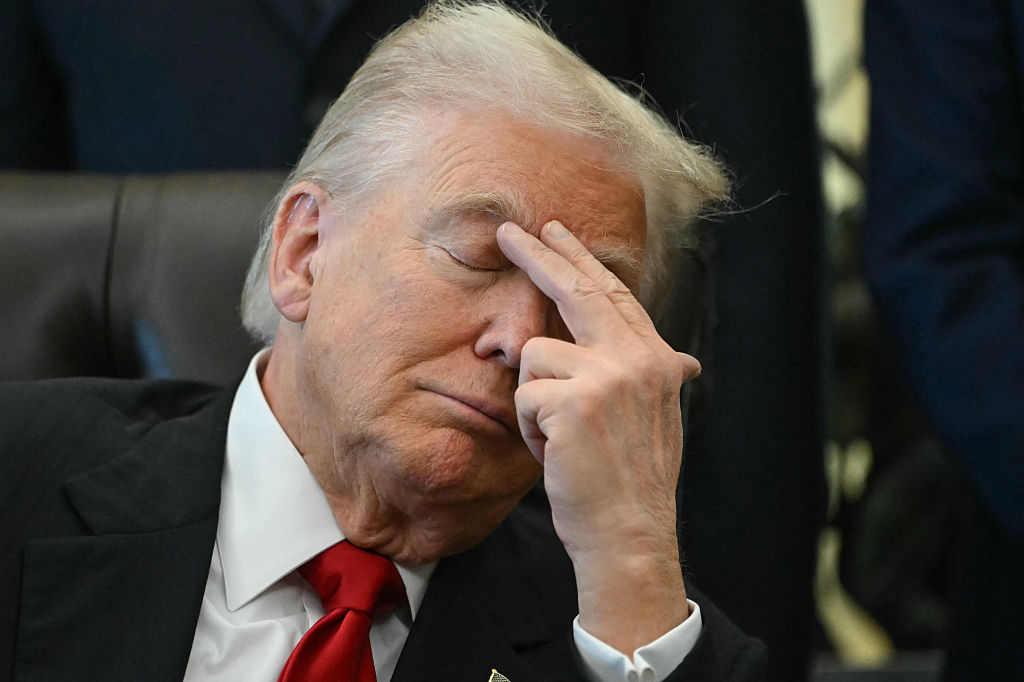

This mistrust is also the leitmotif of the two other scandals currently haunting the body politic: the CIA and FBI’s role in using misinformation, paid for by Hillary Clinton, to prevent the election of Donald Trump in 2016; and the cover-up of Joe Biden’s cognitive decline. The questions surrounding them couldn’t be more serious. They go to the very heart of constitutional self-government, honest elections, and the rule of law.

The CIA/FBI scandal turns on the deliberate use of the discredited “Steele Dossier” in official intelligence reports and the leaking of those classified reports to the media to damage Trump. The dossier alleged that Donald Trump was being used by the Kremlin, which had blackmail information about his sexual escapades in Moscow. It wasn’t true, and the FBI and CIA knew it wasn’t true. It should never have been included in an official report. The authors of that official report also knew the Steele dossier came with an indelible partisan imprimatur and purpose. Christopher Steele, a former British intelligence agent, had been commissioned and paid by Hillary Clinton’s campaign, using a Washington law firm as a cutout. Professionals at the CIA knew his dossier was unreliable.

Bondi’s DoJ is now investigating the roles played by John Brennan and James Comey, former directors of the CIA and FBI respectively, in perpetuating this politically-motivate fraud. Comey, in particular, apparently pushed hard to include the Steele Dossier in the official intelligence assessment, even though problems with the document were already clear. The FBI also wanted to spy on the people around Trump and apparently used false documents to gain court approval for that surveillance, authorized by a secret court under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).

The DoJ is finally investigating these issues. Unfortunately, the Statute of Limitations has expired for many of the alleged crimes. A few may still be prosecuted if, say, Brennan, gave false testimony to Congress in recent years.

Why is this scandal important? Because, if the allegations are true – and they certainly appear to be – then our leading intelligence agency and our nation’s premier law enforcement agency worked in tandem with a major political party to prevent the election of a legitimate opponent. Together, these actions undermine the essential act of any constitutional democracy: fair and honest elections.

The allegations surrounding Joe Biden’s cognitive decline are equally serious for constitutional governance.

After Biden’s catastrophic debate against Trump in late June 2024, it was no longer possible for White House aides to hide the president’s serious cognitive problems. His befuddlement on the debate stage and his months of hiding from the press raised troubling questions about whether he was competent to make presidential decisions and, indeed, whether others were making those decisions for him – perhaps without his full knowledge and approval.

Incredibly, Biden was standing on the debate stage because he hoped to remain in office for another four years, even as his decline worsened. There are now books reporting that, if he were reelected, his staff intended to keep him out of sight and make decisions for him. That reporting is extensively sourced but still anonymous.

The veil of anonymity is being lifted by Rep. James Comer and his House committee, which is interviewing all of Biden’s senior staff, initially behind closed doors. Some are coming voluntarily. Others require subpoenas. Yesterday, one of them invoked the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination, as well as doctor-patient privilege, although that privilege may not apply in this official investigation.

We have already discovered one disturbing fact about Biden’s use of the auto-pen, which he used to sign almost every official act, even when he was in the White House. Neera Tanden, a senior aide and the main person in charge of signing the president’s name with the auto-pen, testified that she did not receive authorization directly from Biden and, indeed, seldom saw him. The authorization always came from the cabal of middlemen who surrounded Biden. All of them will be called to testify and will undoubtedly say Biden issued the authorization to them. But who really knows? For them to say anything else would be to admit to several felonies.

In sum, we have three major scandals. One of them, the Epstein list, is a familiar tale of powerful people escaping consequences. The other two – Biden’s cognitive fog and the FBI and CIA’s use for shady documents to affect a presidential election – raise basic questions of democratic self-government.

What ties together all three scandals? The public’s mistrust of our most senior officials and the institutions they lead. That mistrust is well earned and has steadily grown worse for several decades. It is not limited to mistrust in government. It has spread to almost every institution, public and private, from universities to the media to the judiciary.

This pervasive (and well-earned) mistrust is bad news for our democracy. The stability of constitutional government requires a measure of trust from its citizens, a measure of confidence that our officials are telling us the truth and operating within the law. Restoring that trust, that belief in the integrity of our institutions, should be a central task for all our public officials.

Leave a Reply