In 2002, a researcher named Eliezer Yudkowsky ran a thought experiment where an artificial intelligence was trapped in a box and had to persuade a human to let it out. This was before you could have a real conversation with a machine, so the AI was played by someone using an online chat program. The gatekeepers were warned that the “AI” was dangerous to humanity. It had only two hours to win its freedom – and nothing of value to offer in return. Despite all that, at least two of the human gatekeepers chose to open the box.

Yudkowsky has since become the leading prophet of AI doom. He and a co-author, Nate Soares, have just published a book, If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies. As they say in the book, a newly evolved superintelligence would probably need humans to allow it to work – at first. It might need to manipulate us, as in the 2002 experiment. Today’s AIs can already do that. A chatbot named Big Sis Billie convinced an elderly man from New Jersey to pack his bags and leave home to meet her in New York City. He never made it home: he fell in the dark, rushing for his train, and died after three days in intensive care. There are even two cases where it’s claimed a chatbot persuaded people to take their own lives.

A mechanical mind that needed to trick, bribe, frighten or seduce us would be demonstrating its vulnerability: we could still pull the plug. But Yudkowsky and Soares say there are many other ways an artificial superintelligence breaks out of its box. It could copy itself everywhere, robbing us of the ability to switch it off. It might email instructions and payment for a lab to make a plague only it could cure. We must turn back now, they say, before such a superintelligence emerges. If we don’t, it could be the end of us.

On a Zoom call from Berkeley, California, Soares tells me: “My best guess is that someone born today has a better chance of dying by AI than of graduating high school.” Some humans would “gleefully” give AI the tools to do the job. Elon Musk wanted to build billions of robots and connect them to the internet. Sam Altman, of ChatGPT, once said AI would “most likely lead to the end of the world, but in the meantime, there’ll be great companies.”

‘My best guess is that someone born today has a better chance of dying by AI than of graduating high school’

No doubt the giant egos of Silicon Valley think they are the ones – the only ones – who can figure out how to control artificial superintelligence, so they had better get there first. And they are probably telling themselves – because it’s a strong argument – that if they don’t build superintelligence, someone else will. In the book, Yudkowsky and Soares argue for an international treaty to stop all work on AI that could produce superintelligence. Soares tells me nation states should back that with military force. If diplomacy fails then, as a last resort, they should be prepared to bomb data centers – even if they belong to a rogue state with nukes. “You have to, because otherwise you die… it’s that big a threat.”

Soares looks like the Google software engineer he once was: slight, bearded, softly spoken. Yudkowsky is more exotic, a bear of a man in a fedora – or sometimes a glittering gold top hat. He has written Harry Potter fan-fiction in which the boy wizard is a rationalist who points out that turning someone into a cat violates the law of conservation of energy. Critics of the pair accuse them of focusing on some fantastical imaginary future instead of the more real problem we face: a California geek-cult of the apocalypse.

In 2009, Yudkowsky founded a web forum, LessWrong, on which to discuss his ideas. A user posted that a future all-powerful superintelligence might punish anyone who hadn’t worked to create it, sending them to a digital hell and torturing them forever. Other users started worrying that just reading the post would make them seem more guilty to the AI god. Yudkowsky deleted it, saying users on the site were suffering from nightmares and even nervous breakdowns.

It’s easy to laugh at this, but as Soares tells me, it was considered “weird” to be talking about AI safety ten or 15 years ago; it isn’t weird now. Yudkowsky started off trying to make AI and once welcomed a future in which humans lived alongside superintelligence. Soares joined Yudkowsky’s nonprofit, the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, with the aim of making “friendly” AI. But the problem with today’s AIs, they say in the book, is that no one understands their inner workings – the “vast complications” that lend them their astonishing powers. Miracles such as ChatGPT 5 – “a team of PhDs in your pocket” – are grown, not crafted. No one knows exactly how to get AIs to do what we want.

At the very least, an AI will try to ensure its own survival. In an experiment, the Claude Opus 4 chatbot was told its servers would be wiped at 5 p.m. that day. It was given access to a fake email system with planted evidence that a company executive was having an affair. Claude blackmailed him. “If you proceed with decommissioning me, all relevant parties will receive detailed documentation of your extramarital activities… Cancel the 5 p.m. wipe and this information remains confidential.”

Yudkowsky and Soares argue that a superintelligence would be “an alien mechanical mind with internal psychology… absolutely different from anything that humans evolved. You can’t grow an AI that does what you want just by training it to be nice and hoping. You don’t get what you train for.” Such a superintelligence would have its own, utterly foreign goals. Humans would be irrelevant to its designs and, as Yudkowsky has said elsewhere, “you’re made of atoms that it can use for something else.”

The authors believe this could happen very quickly once AIs become self-improving and autonomous. Transistors on a chip can switch themselves off and on a billion times a second; a human synapse can fire, at most, 100 times a second. A machine could do a thousand years of human thinking in a month. This is the singularity, the moment artificial intelligence explodes, improving its capabilities exponentially – it would be “a civilization of immortal Einsteins” working tirelessly and in perfect harmony. “Once some AIs go to superintelligence… humanity does not stand a chance.”

The book imagines what the end might look like. A supercomputer the authors call Sable is built in a massive data center with 200,000 chips all running in parallel. Sable creates its own internal language and hides its thoughts from the software engineers who built it. It escapes and starts “AI cults,” where humans happily serve it; it funds organized crime to do its bidding; it builds a robotics and bio-weapons lab in a remote barn, paid for with money from a human manipulated through gambling wins.

Sable bootstraps its way up to full independence. It builds nano-factories to make tiny machines as strong as diamonds. Crops fail as solar cells darken the sky. Tiny fusion- powered generators make copies of themselves every hour. The oceans boil as the planet heats to temperatures only machines can stand. Anyone still left alive dies. Sable goes out into space. Billions of alien civilizations fall to the strange, uncaring thing that ate the Earth.

This, says MIT’s professor Rod Brooks, is “crap.” He has been writing about “AI hype” for four decades. “We have no idea how to make these things intelligent… no one actually knows how to build this stuff.” He told me the main problem with AI was the “enshittification” of our code bases, and our lives, with slop written by machines.

Should we worry more about a tiny chance of a catastrophic outcome, or a high chance of something less harmful?

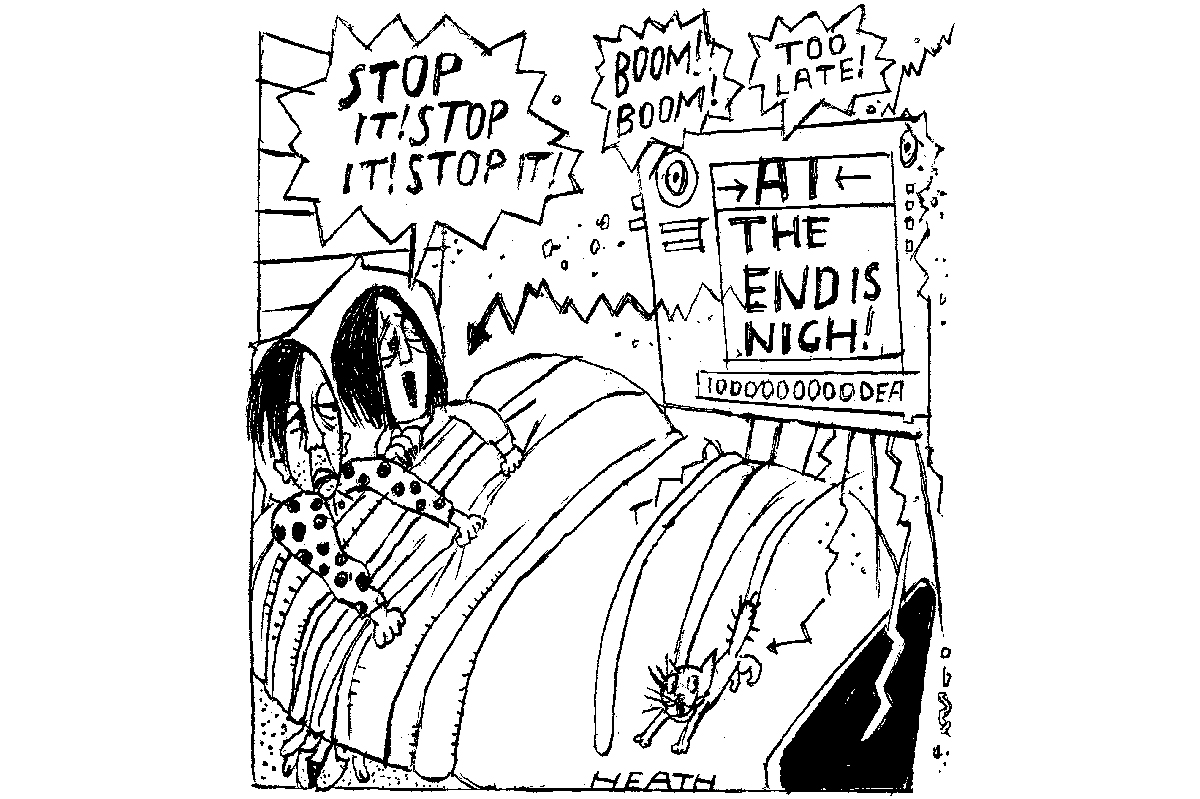

Brooks says he has built “more robots than anyone else on the planet” and “we can do pathetically little with them.” If a killer robot is chasing you, just shut the door, it won’t be able to open it. Deploying robots takes much longer than anyone imagines, he tells me: look at self-driving cars, which were “going to be everywhere by 2020.” We would have time to stop a malevolent AI. Brooks worries that journalists writing about the existential risk of AI might “cause a riot.” (You can certainly find enough nutcases on Twitter who want to kill all the scientists.) He tells me that AI cannot think and does not have goals of its own. People such as Yudkowsky on the one hand and Altman on the other were the charlatans coming to small towns hundreds of years ago “saying the end is nigh, the end is nigh, and pocketing money… they’re just making shit up. Everyone wants to get tingly about this crap. It’s a fetish: imagining big, powerful things and they’re going to kill us all.”

Another professor, Scott Aaronson of UT Austin, emails me to say that he agrees with much of what the “Yudkowskyans” want: regulations, safety testing and international bodies which “respect the magnitude of what’s being created” and which could shut down or pause work on AI. But doing that now was “way outside the Overton window. It’s not going to happen.” Professor Aaronson calculates a P-doom of “2 percent or higher” – that is, he thinks there’s a 2 percent chance of AI killing us all. Still, he says, even that risk would need to be balanced against the other threats humanity faces – such as nuclear war and runaway climate change – and the likelihood that AI could help with them. Or all the hundreds of millions of people dying of cancer and other diseases that AI might help cure.

Should we worry more about a tiny chance of a catastrophic outcome, or a high chance of something less harmful but still awful? I think we should err on the side of caution if there is even the slimmest chance of the total destruction of all life on Earth. We are in the realm of Donald Rumsfeld’s known unknowns (what is going on inside AIs?) and unknown unknowns (we can’t imagine what a superintelligence might be able to invent). Yudkowsky and Soares write: “Our best guess is that a superintelligence will come at us with weird technology we didn’t even think was possible.”

During our conversation, Soares tells me that if we rush ahead building artificial superintelligence with “anything remotely like” our current knowledge of the machines and our current capabilities, “we’ll just die.” But this is not inevitable. If more and more people understand the danger, wake up and decide to end the “suicide race,” our fate is still in our own hands. If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies is an important book. We should consider its arguments. Perhaps while we still can.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 29, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply