Our latest visitor from interstellar space is leaving us. It reached its closest point to the Sun on October 29 and is now heading back toward the stars at great speed, having spent a few months traversing our region of space.

This visitor – a comet called 3I/Atlas – scared some, fascinated astronomers and thrilled us all as we marveled at its strange journey. 3I/Atlas, which Michael P. Gibson introduced Spectator readers to in the last issue of this magazine, got its name because it is the third object ever found to have entered our solar system from interstellar space – and Atlas is the name of the sky survey that found it as a point of light moving against the distant stars.

The first interstellar visitor was Oumuamua, a strange, elongated rock detected in October 2017, some 40 days after its closest approach to the Sun. Then came Comet 2I/Borisov in 2019, a chunk of rock and ice from another solar system that, due to the warmth of its solar passage, developed a tail of gas and dust. (This is quite normal.) Because of these visitors, astronomers were on the lookout for another one.

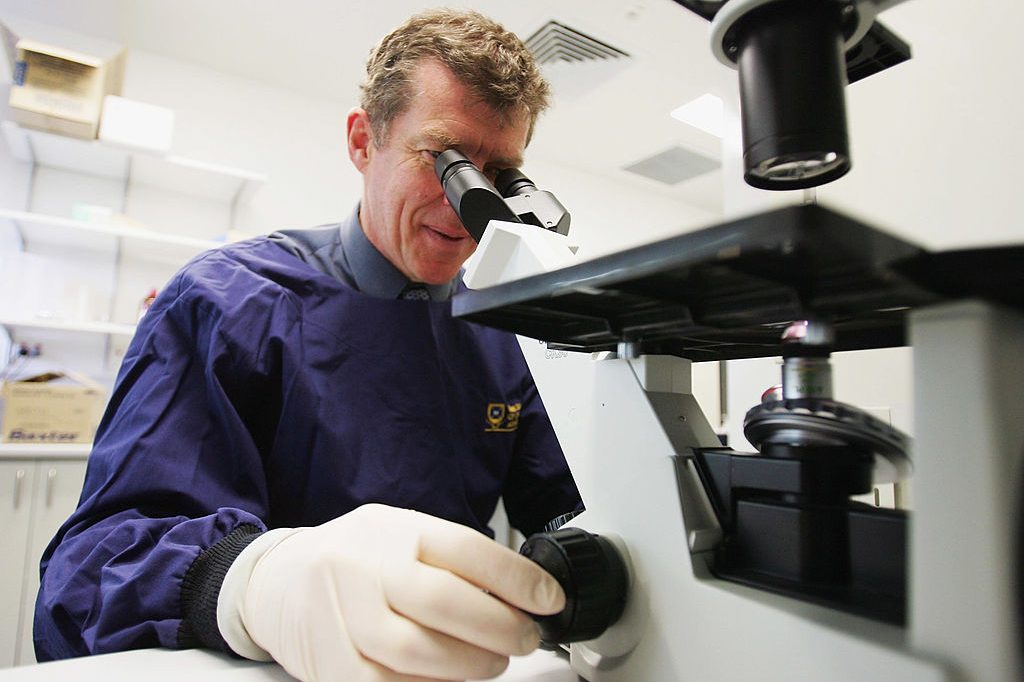

3I/Atlas was discovered on July 1 as it swooped into our solar system from the general direction of the center of our galaxy. Dozens of the world’s most powerful telescopes have been turned toward it, including the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope and, when a few weeks ago it passed Mars, satellites orbiting the red planet looked at it as well. You need a telescope to see it.

Comets are essentially just shards of ice and rock made from the leftovers of planetary formation. All normal stars are formed out of collapsing clouds of gas and dust. Around the nascent star will also be planets and, further out, a cloud of comets. Frozen and lifeless, they will only become active when a gravitational disturbance causes then to fall starward, where they heat up and develop a dusty shroud as well as tails of gas and dust.

But not all comets will visit their parent star; many will be shaken loose to wander undetectable between the stars. In our galaxy alone there could be more interstellar comets than there are stars in the entire universe. One of the earliest stars to form after the Big Bang created 3I/Atlas. Observations suggest it is older than the Earth and Sun. It may have been traveling for almost as long as the universe has existed. Hence the scientific fascination with this cosmic time capsule.

The latest leg of its eternal journey through the immensity of interstellar space saw it approach a bright yellow star. Though its previous destinations were undistinguished, this time the comet would approach much closer than usual, passing big and little worlds on its way. One of them was an unusual blue color and from it scientists became, almost certainly, the first sentient creatures to observe it. The warmth from our Sun was increasing, and the iceberg was beginning to thaw. Its surface stirred for the first time in billions of years.

Imagine if you stood on 3I/Atlas. At a few miles across, its gravity would be slight. You could jump and take several weeks to fall back to its surface. You’d have to be careful where you walked because even though you weigh almost nothing, the comet’s surface is fragile. Perhaps you could get to its equator, make a snowball and hold it out. Release it and it would seem to hover due to the slight forces controlling it. Nearing the Sun, you would see ice and dust geysers form the familiar tail of comets. You could see them sparkling in the sunlight and billowing in the solar wind as they arc out into space.

How wonderful comets are. Over the ages they have inspired and frightened. A few times in each human lifetime there will be a fine comet. Most were observed in prerecorded history spawning legends, but in more recent times they shook the Chinese emperor’s heavenly mandate to rule; proclaimed doom to Aztec Emperor Montezuma II just before the cataclysmic arrival of Hernán Cortes; and inspired Shakespeare to have Calpurnia say, in Julius Caesar, “When beggars die, there are no comets seen; the heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes.” In 1910 there was global pandemonium when some suggested that the Earth might pass through the tail of Halley’s Comet and be poisoned by its trace component cyanogen. It couldn’t have happened.

Comet 3I/Atlas has brought its fair share of pandemonium. The internet was rife with conspiracy theories and claims it was an invading starship, bolstered by misrepresentations and lies about the data reported with nonexistent standards of assessing evidence and knowledge of basic science. Let them have their fun. But we should not be as dismissive of Professor Avi Loeb, of Harvard University, who, under the guise of “raising awareness” of the issue of possible alien invasion, created waves of publicity saying that, on the one hand, it isn’t aliens – and on the other, it is.

With the increasing depth and completeness of surveys of the sky, we will find many more of these interstellar visitors. There have been suggestions that we should place a probe in a parking orbit ready to rendezvous with one of these interlopers. But not Comet 3I/Atlas.

Soon it will be gone – and no human will ever see it again. We wait for the next one as Flaubert said, running like horses in the field of space. Comets, predictable or otherwise, are the marvels of the sky, holding a special place for us. Comets mark our progress, our sense of wonder and our fears.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply