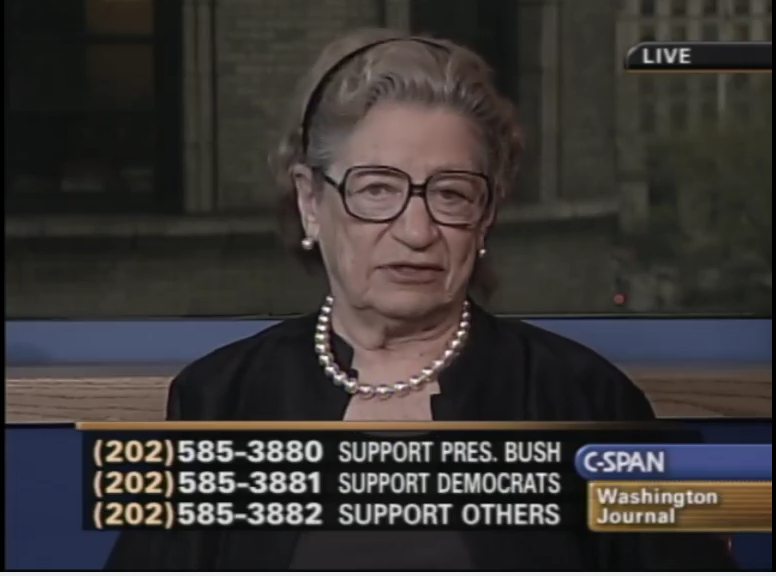

Conservative editor and writer Midge Decter has died. She was 94. She was an executive editor at Harper’s and an editor at Basic Books, as well as the founder of the Independent Women’s Forum, co-chair of the Committee for the Free World, a board member of the Heritage Foundation, and one-time president of the Philadelphia Society. She married Norman Podhoretz in 1956 and is the mother John Podhoretz, current editor of Commentary, and journalist Ruthie Blum.

In National Review, Yuval Levin remembers her as a “powerful and penetrating writer.” He writes:

Her essays could see right to the core of the failures of the modern left — often long before those failures become apparent as a practical matter to everyone with eyes to see. Her early collections, The Liberated Woman and The New Chastity, from the early 1970s, are full of insights that our society would take decades to grasp, but which Decter could see in real time because she took the radicals’ unseriousness seriously and understood where their moral recklessness would lead. Liberal Parents, Radical Children, written in the mid-‘70s, reached even deeper, recognizing the complicated ways in which the parents of the Baby Boomers were responsible for what most troubled them about their children.

The need to take responsibility for what was breaking down in our society was a theme to which she would recur for decades — refusing to let Americans get away with blaming the degradation of our culture on anyone but ourselves.

For Joseph Bottum in the New York Post, she was “one of those people who made things happen”:

From a place among what were called the New York Intellectuals of the 1950s — the mostly Jewish writers and thinkers who congregated in Manhattan — Midge emerged as the den mother of the old social-science form of neoconservatism in the 1960s and ’70s. From there it was a simple step to becoming the earth mother who helped hold together all the writers and thinkers in the big tent of Reaganite conservatives during the 1980s and 1990s. They squabbled endlessly with one another, but they would all come when Midge Decter called … She was one of those people who made things happen, one of those women who pushed things along.

I shared an office with Midge in the mid-’90s, editing together at a job for which there wasn’t really enough work for both of us. And so we filled our days with chain-smoking and conversation. For her, it was a chance to tell stories of the political dim lights of such literary luminaries as Robert Lowell and Alfred Kazin, the knotted lives of Lionel and Diana Trilling, the glibness and wildness of Pat Moynihan, the gentleness of Robert Warshow, the sternness of Jeane Kirkpatrick.

For me, fresh out of graduate school, it was an education. The New York in which she moved while young is gone. The intellectual battles she fought have faded into history. But the lessons she taught about activity, strength of character and good-natured argument remain unchanged from generation to generation.

In First Things, where Decter contributed regularly and worked as an editor, R.R. Reno writes, among other things, about her talent for editing:

“Let me think about it,” Midge Decter said. It was early in 2014. I was looking for a senior editor, and had called Midge to get her opinion about who might be good. We discussed some people, but none of them seemed quite right. And so I asked, “What about coming to work at First Things for a few months so that we can find the right person?” “But I’m old,” she objected. “Yeah,” I replied, “but you’re the best.” The next day she called and said, “Sure, I’ll do it.”

Her stint working for me was not her first time at First Things. In the 1990s, she had had a position at the magazine under our founder, Richard John Neuhaus. By her account, RJN had offered the job by asking, “Midge, why don’t you come down and hang out with us?” Her affection for our founder and loyalty to our enterprise was boundless. As the magazine’s current editor, I often received her encouragement, which was always warm and rich with the offer of friendship.

Her standards were high. On her first morning at work, Midge came into my office, asking for an assignment. I gave her four manuscripts. She retreated to her office. At noon, she presented herself: “These aren’t very good. They’re not for us.” I told her, “They are the features for the next issue.” Sighing, she replied, “OK, I’ll work on them.” Which she did, blue-penciling the manuscripts and painstakingly making the not-so-good essays into something at least better, if not perfect.

She will be sorely missed.

In other news

Daniel J. Flynn reviews a new biography of Willmoore Kendall:

Some people remember William F. Buckley, Jr., by his line, “I would rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone directory than by the 2,000 people on the faculty of Harvard University.” But the quip has much less to do with Buckley’s political orientation than with that of his teacher Willmoore Kendall. Other Kendall students — Hubert Humphrey, Russell Long, and Brent Bozell among them — also attest to his influence, but his imprint glares most clearly on people who neither read him nor know his name.

Jospeh Epstein on the essays of Charles Lamb:

Smallish, with a serious stammer, a drinking problem, and more than a taint of insanity running in his family, Charles Lamb was not dealt the best of hands.

Bono to publish a memoir (his first) this November:

Surrender, which will “draw in detail” what he had previously only sketched in songs, will contain 40 chapters, each named after a U2 song, and include 40 original drawings by the singer.

An author’s online essay on why she used plagiarized material in a novel pulled earlier this year has itself been removed after editors found she had again lifted material. Jumi Bello’s essay, “I Plagiarized Parts of My Debut Novel. Here’s Why” appeared just briefly on Monday on the website Literary Hub. Bello’s debut novel, The Leaving, had been scheduled to come out in July, but was cancelled in February by Riverhead Books.

Standing with of J.K. Rowling:

When Roland Barthes wrote his 1967 essay “The Death of the Author,” he probably didn’t intend that, fifty-five years later, a major American news outlet would be provocatively suggesting that the world’s bestselling author should be de-personed, de-platformed or de-materialized from history. And yet that is exactly what has happened with the New York Times. They recently ran a series of advertisements on the subway featuring a reader named “Lianna” who is, as much of their subscriber base now are, “breaking the binary,” experiencing “queer love in color” and meditating on “heritage in rich cues.” So far, so predictable. But the ads took a grimmer turn when one suggested that Lianna was “imagining Harry Potter without its creator.” This example of what the Times calls “independent journalism for an independent life” has taken up one of the most disquieting contemporary developments in the culture wars, as the newspaper has shamelessly monetized it for promotional purposes.

People need to stop publicly apologizing, says Freddie DeBoer, and I kinda agree with him:

Apology itself is good. But public apology is a useless and self-defeating ritual. If you have done something wrong to another, I recommend that you privately apologize to them. That person can then accept your apology or not. They can publicize your apology or not. But all of the moral value of apologizing will be preserved, while nothing of practical value to your life will be lost. Look, if nothing else it’s indisputable that public apology has no consistent ability to reduce criticism, and I think it’s obvious that in fact such apologies just show that blood is in the water. You’ve heard it from me many times: there’s a profound nihilism in American life right now about the potential for positive change. So many people, of so many political stripes, have given up. And I think that plus the truly ruinous and sadistic influence of social networks and their reward systems have created this ever-seething mob that constantly casts around for its next scalp. We can’t get real change, but by god, we can make people cower! You can’t apologize to that. You shouldn’t negotiate with terrorists.