Last week it was announced that Kate Clanchy has parted ways with her publisher, Pan Macmillan. Who is Kate Clanchy? She is an award-winning poet and teacher whose latest book, Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me, won the 2020 Orwell Prize. The book is the story of her poetry students who contributed to the anthology she edited, England: Poems from a School, and an analysis of how public schooling has changed in England.

Why has she parted ways with Pan Macmillan? A year ago some people on social media criticized Some Kids I Taught for containing racial stereotypes. Her former students — including those included in the anthology — defended her, but to no avail. Clanchy at first defended the book but then agreed to rewrite it for a revised edition.

But the two parties apparently decided to part ways altogether: “Pan Macmillan and author Kate Clanchy have parted company ‘by mutual consent’, with the publisher reverting the rights and ceasing distribution of all her work following criticism of Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me . . . Picador had announced it was working with Clanchy on a revised version of the book. However, a joint statement by Pan Macmillan and Clanchy today (20th January) said this would no longer be published and the two parties were going their separate ways. It said in a statement: ‘By mutual agreement, Pan Macmillan and Kate Clanchy have decided to part company. Pan Macmillan will not publish new titles nor any updated editions from Kate Clanchy, and will revert the rights and cease distribution of Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me and her other works.’”

Sonia Sodha writes in defense of Clanchy in The Guardian:

“It is true that Clanchy reacted badly to the criticism, denying the phrases in question were in her book. Defensiveness is a flawed but common response when being charged with something you abhor. But both she and Pan Macmillan issued apologies for the offence the book caused and her publisher announced she would rewrite it to address concerns. One might think that that would have drawn a line, enabling the industry to move on to issues about its lack of diversity, which Clanchy has done more than many of her critics to address.

“It did not. Pan Macmillan was further berated for giving her the opportunity to make amends by rewriting. After her publisher, Picador imprint’s Philip Gwyn Jones, rightly reflected that he wished he had been clearer about its support for Clanchy and her rights, alongside condemning the online abuse and trolling by her critics, he issued an apology for causing further hurt that read like a hostage note: ‘I now understand I must use my privileged position as a white middle-class gatekeeper with more awareness.’”

There is no opportunity for redemption in this new international self-righteous secular puritanism. Sodha goes on to note how much Clanchy had done for poor British and immigrant children, which now apparently counts for nothing.

What does Clanchy make of all this? She writes in UnHerd that this new kind of moralistic approach to literary texts is, among other things, brazenly dishonest:

“Overt argument or evident intention are often, in this new criticism, less important than the critic’s own linguistic detective work — bias, after all, is always unconscious. For my introduction to England Poems from a School, for example, Parmar is not to be fooled by the lengthy argument about multilingualism and the inheritance of poetries, nor sentences such as ‘it is impossible to overstate profound and multi-layered are the forces of cultural silencing; or how strong and subtle is the belief that poetry belongs only to the privileged’. She skips past them, in order to pluck out that single word ‘striving’ — which I agree, makes me sound like the Daily Express when describing migrant families — and conjures me on its evidence as a memsahib, teaching English as ‘a linguistic and disciplinary tool of colonial domination’.

“As Parmar sternly asserts, isn’t it true that this country ‘is not (nor has ever been) tolerant or kind towards non-white people’? Multiculturalism’s answers can never match such absolutist rhetoric . . . Professor Parmar is American by upbringing, privately educated in California. She does not have the experience of sitting in a classroom where most students were not born in the UK, but in every continent of the globe, a classroom where there is no majority group — that’s a uniquely 21st-century, English thing. But I have. I experience these classrooms as exceptionally kind and creative places where young people hear and listen to each other openly and deeply; make cross-racial and cross-cultural friendships that endure, and, far from being ‘dominated’ by English, remake the language daily in thrilling ways. Poems grow there readily, and poems, also in my experience, do not grow from cruelty, but from confidence and affirmation.”

Ouch.

In other news

Barton Swaim revisits Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution: “The book, when it finally appeared, outraged some reviewers, delighted others and was talked about by everybody. Carlyle was only 42 at the time, but he quickly acquired the reputation of a sage . . . Carlyle’s philosophy is often described as an expression of ‘might makes right’ and authoritarianism. That is wrong—he always insisted that the right to rule was valid only if exercised with charity and justice—but he lent credence to early-20th-century arguments for autocratic rule. His later works, particularly the frenetic ‘Latter-Day Pamphlets’ (1850), indulged in bigoted language about the enslaved and did much to harm his reputation. Carlyle is still worth reading, if for no other reason than that he shaped European political thought for two generations. Mill, whose friendship with Carlyle cooled in the 1840s, consciously defined his own radical liberal outlook against the Carlylean ethic. The American Transcendentalists revered Carlyle. Marx and Engels both praised and misunderstood him. Friedrich Nietzsche hated him, sharply describing Carlyle as ‘an English Atheist who makes it a point of honour not to be so,’ but the German philosopher clearly mimicked Carlyle’s fiery style and borrowed from his worldview.”

A 2,000-year-old Roman glass bowl discovered in the Netherlands looks like new: “Archeologists excavating in Nijmegen, the Netherland’s oldest city, found the bowl in pristine condition.”

The Chinese government changes the ending of Fight Club: “The version now playing on China’s largest video streamer, which is home to the country’s biggest selection of imported films, stops before the buildings explode. The final action is instead replaced with an English-language title card explaining that the anarchic plot was foiled by the authorities.”

The voice of the original Charlie Brown has died, and by his own hand, sadly: “Robbins’ family confirmed his death, although a rep did not immediately return Rolling Stone’s request for comment. The actor had long struggled with mental illness and bipolar disorder, while he also battled drug and alcohol addiction, and had several stints in prison.”

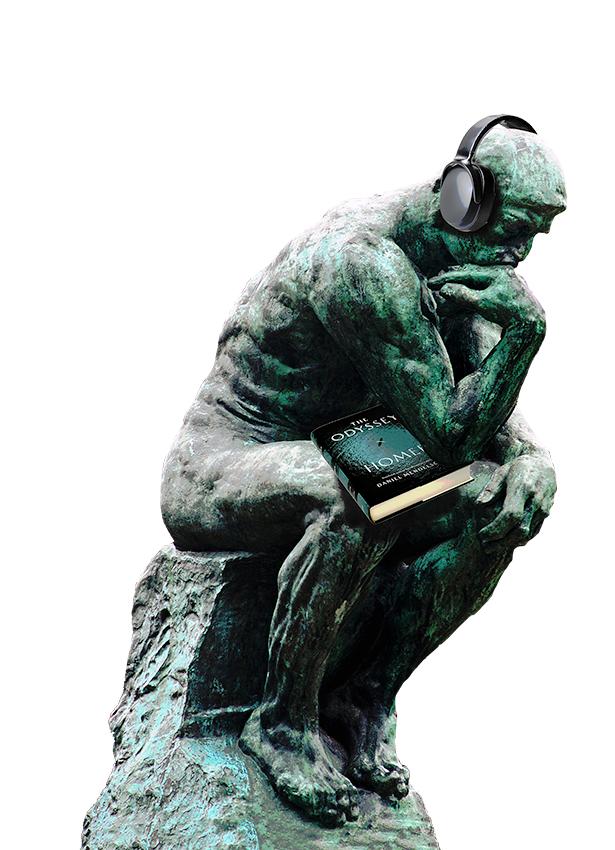

Bruce Whiteman reviews a new translation of Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal: “There have been many translations of Baudelaire’s poems into English since the oddly titled Translations from Charles Baudelaire, with a Few Original Poems of 1869, which appeared only two years after the poet’s death . . . A new translation by the poet Aaron Poochigian, published to coincide with Baudelaire’s bicentenary, includes all the poems from the second edition of 1861 as well as the poems that were censored by the authorities and ordered cut from the book, but excludes the ‘Nouvelles Fleurs du mal.’ Poochigian was trained as a classicist and is better known as a translator of ancient Greek writers, including Sappho, whose poems and fragments he published under the title Stung with Love. Sappho, who never rhymed a line in her life, became a kind of Neo-Formalist in Poochigian’s version, in which all the poems rhyme and have a regular meter more characteristic of English than of ancient Greek. Baudelaire, by contrast, does not need to be conscripted into the Formalist army. Apart from his later influential experiments with the prose poem, the poems in Les Fleurs du mal are all metered and rhyme.”

A life of Stephen Crane: “The youngest of 14 children of a Methodist preacher and his wife, Crane was born in Newark, N.J. Only nine of the children survived infancy. The family frequently moved as his father was transferred to various parishes. Stevie, as he was called, began to read at four. At the same age, he nearly drowned in New Jersey’s Raritan River because he fearlessly walked into it until the water was up to his face. He would have gone under if an older brother hadn’t pulled him out. After his father died, when Crane was eight, his mother supported the family by working as a freelance writer of religious articles for Methodist publications. The daughter and sister of Methodist ministers, she was strict in her religious beliefs and crusaded against gambling, smoking, drinking, dancing, and other frivolous activities, including the reading of novels.”