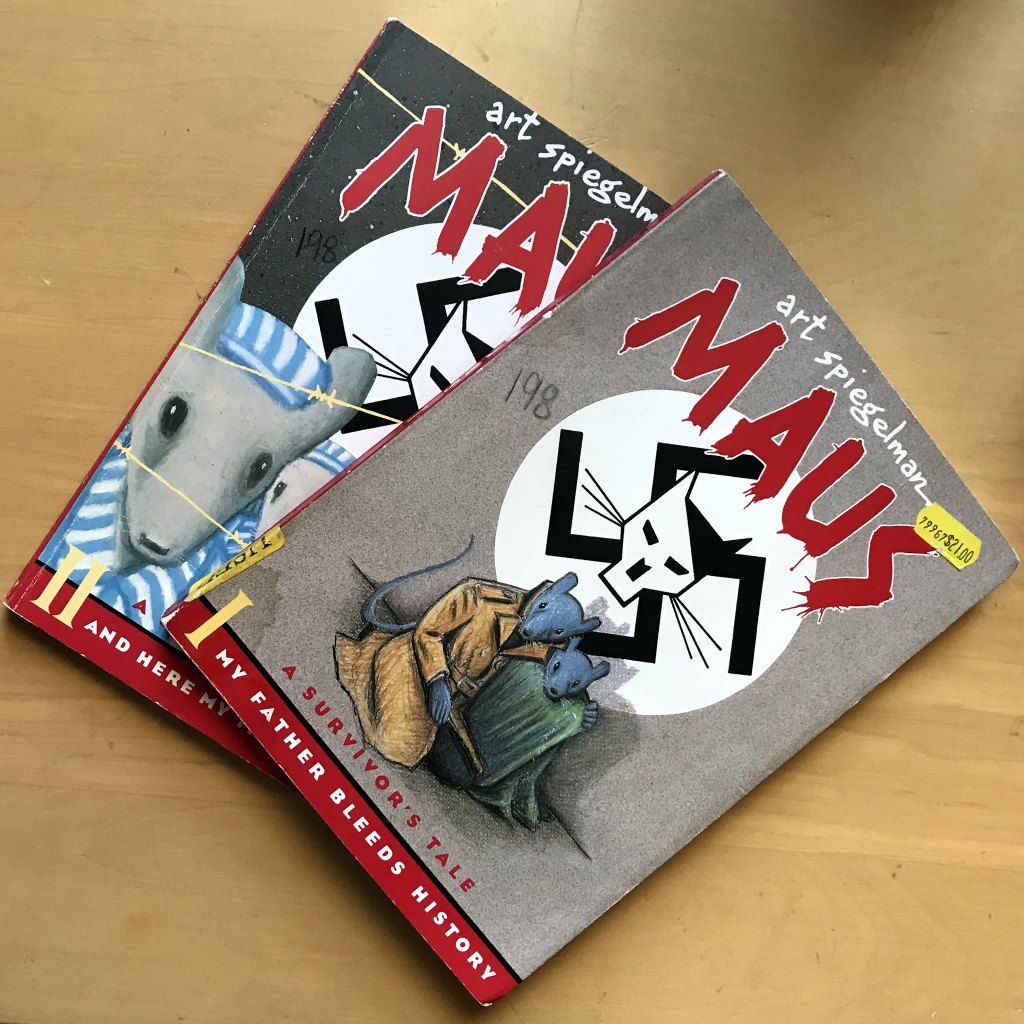

Whatever one thinks about the school board in McMinn County, Tennessee removing Maus from the curriculum, it isn’t “banning,” Thomas Balazs argues in a level-headed piece at Quillette. The school board voted to remove it from the required curriculum, which isn’t the same thing as removing it from the library:

Both the content and artwork in this section are difficult to absorb, not just because of the bathtub scene, but also because the expressionist illustrations are distorted and sometimes grotesque. At a time when teen suicide is at an all-time high, this section alone may have caused some parents and board members understandable concern.

And then, of course, there’s the devastating Holocaust imagery that includes piles of dead bodies, hanged men, and a child being smashed to death against a wall by a Nazi soldier. Whether it’s the murder of Jews, the death of his mother, the story of an affair Spiegelman’s father conducted before the war, the resentment the artist expresses toward his parents, his father’s toxic second marriage, or the stark black-and-white drawings, the whole tone and tenor of the novel is adult. Does this mean young teenagers shouldn’t be allowed to read Maus? No, of course not. It does mean, however, that it’s not completely unreasonable for a parent or educator to reserve this book for older readers who will be better placed to understand and appreciate its importance and value.

But this is real life, people say, and kids have to learn that this is the way the world is. As a second-generation Holocaust survivor myself, this is an impulse I understand. I, too, have experienced periods when I wanted to wreck the world’s innocence because of what my family went through. But it is also an impulse to which Spiegelman himself offers a subtle rebuke in the very first pages of Maus. As a young boy, Spiegelman runs home in tears when his friends abandon him after a skating accident. “Friends? Your Friends?” his father says bitterly when confronted with his distraught son. “If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week … then you could see what is friends!” This vignette illustrates how survivors’ trauma can be passed from one generation to the next.

It’s the only explanation I can think of for Spiegelman’s apoplectic loss of perspective on this issue: You want to protect kids from the world? Let me tell you something about the world. But it’s not wise or fair, as Spiegelman himself implies in his own novel, to force others to confront the horrors we have experienced before they are ready. I find Spiegelman’s lack of self-awareness on this point disturbing. ‘I also understand that Tennessee is obviously demented,’ he has said in an interview. What sort of writer accuses people of being demented for not compelling their children to read his book?

Balazs goes on to write that while he thinks Maus is “important,” “it is not the sine qua non of Holocaust literature.” He continues:

I understand perfectly why Maus is great. It was important in my life. It helped me to understand my father, who was a lot like Spiegelman’s. That doesn’t mean I get to insist that every county in the country include the book in their eighth-grade Holocaust program. I don’t know the kids in McMinn County, but I doubt they’ll become Nazis because they didn’t get to read Maus until ninth grade. Nor will they become degenerates if they read it in seventh grade. But it’s not my call (or yours) unless you live in that county.

That last point is an important one. Decisions about what should or should not be in a district’s curriculum is between the parents concerned and the school board. If parents don’t like the school boards decisions, they can replace them at the next election.

In other news

The novelist, Eugene Vodolazkin, writes about the modern and medieval approaches to history: “Modern historical consciousness takes for granted the idea of progress, whereby the present supersedes the past. In the Middle Ages, the present was seen as existing alongside the past: Both were under the eye of God, and so what really mattered was the link each event had with the heavens above, not with the immediate past or present . . . If anything, whereas the Modern Age looks forward eagerly, the Middle Ages looked back.”

David Bentley Hart reviews David J. Chalmers’s new book, Reality+:

His basic position is that of a philosophical naturalist who is nonetheless not a physicalist. That is, he rejects any explanations that exceed natural causes, but he does not assume that the category of the natural is exhausted by material exchanges of energy. He therefore embraces a form of “property dualism” (or “dual aspect” theory) in attempting to account for mental activity; for him, mind is real and really distinct from the physical, but is nevertheless a natural phenomenon . . . In any event, and all things considered, Chalmers has an honorable record as an accomplished and interesting thinker and writer. Were this not the case, his most recent book, Reality+, would not be quite as severe a disappointment as it ultimately is.

D.J. Taylor reviews a biography of the British writer and editor John Collings Squire: “The popular notion of Squire as a reactionary ogre bent on marshalling the forces of conservatism against ‘cleverness’ and verse libre is, as John Smart shows in this absorbing biography, rather misleading.”

“A strong sense of the apocalyptic runs through the book,” John Wilson writes of Cynthia Haven’s Czeslaw Milosz: A California Life, “which is only fitting for the life of Milosz, who experienced one ‘end of the world’ in Poland before moving to California.”

I write about cycling the Blue Ridge Parkway and the history of exercise: “To prepare for the Parkway, I did a very modern thing: I spent hours in a dark basement sweating on a trainer. I say modern because of the technology, but our obsession with working out seems very modern, too. It is an odd thing to spend hours exercising — screen illumined, earphones in — to get better at exercising. But Bill Hayes argues in his entertaining new book, Sweat: A History of Exercise, that working out is not so new.”

Barton Swaim reviews a new book on how “radical” social change supposedly happens:

The conviction animating Gal Beckerman’s The Quiet Before: On the Unexpected Origins of Radical Ideas holds that social media, and online communications generally, are not optimal venues for the development of ‘radical’ ideas. What radical ideas need in order to flourish, he contends, is sustained, patient debate among committed people with a shared, well-defined ideology. In the past these ideas percolated for a long time in pubs and coffeehouses, pamphlets and small-circulation dissident newspapers, before they burst into public life in the fullness of time. Now, Mr. Beckerman laments, they come and go with regularity on a dizzying array of electronic platforms.

Christopher Caldwell writes in praise of tweed jackets: “A tweed, like a blue blazer or a business suit, can be an elegant article of clothing and is usually expensive. But you wear it to blend in, not to stand out. A tweed confers, and expresses, the manly freedom of paying no mind to one’s appearance.”