Donald Trump’s victory this time may not be the surprise that his 2016 win was, but for his critics it’s even more of a shock. Trump has been impeached, arrested, convicted, shot at and relentlessly demonized as a “fascist” over the last four years. None of that was enough to stop him. Just the opposite: Trump is more popular than ever — and appears to have won a national majority of the vote for the first time.

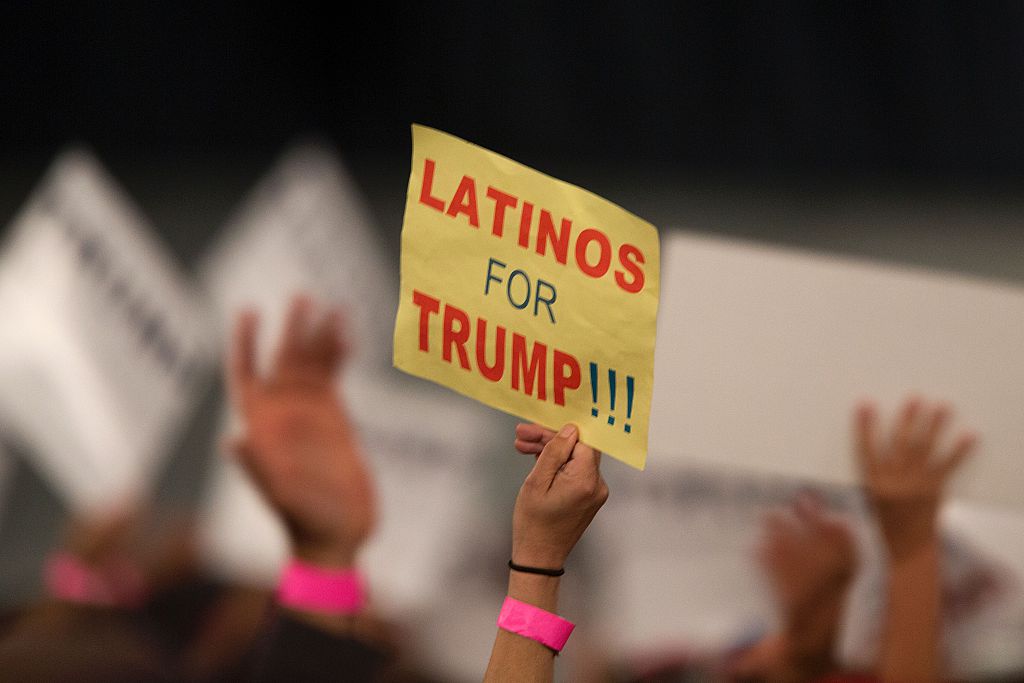

Just how this happened is a question that will be analyzed for weeks and months, or years, to come. But one intriguing possibility suggested by exit poll data is that multiculturalism committed suicide. Trump appears to have won a much larger percentage of the Latino population, especially men, than Democrats had ever thought possible.

Trump becomes only the second president in American history to win non-consecutive terms

The conventional wisdom of American politics is that Latinos are offended by anti-immigration rhetoric, since many of them have recent immigrant roots. (Though others have roots deeper than those of most white Americans — many US states were Spanish territories, after all.) But a glance at the historical politics of ethnicity and immigration in America would show why the conventional wisdom isn’t really so smart: the “white ethnics” who immigrated to the United States in the early twentieth century from southern and eastern Europe tended over time to become a component of late twentieth-century right-wing populism. These minorities formed part of Richard Nixon’s “Silent Majority.” They hated left-wing cultural attitudes of the sort that we would now call “political correctness” or “wokeism.”

At first, white ethnics voted for Democrats such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, who offered them economic security. But once they were established, they found the anti-leftist — and in the twentieth-century, specifically anti-communist — views of right-wing Republicans more to their liking. They also were none too keen on the newer waves of immigrants coming in after their own parents’ or grandparents’ generation.

From the 1970s until today, progressives and liberals have tended to deplore white ethnics as bigots who were uncomfortable with non-white immigration. Trump’s success with Latinos, however, suggests a different interpretation. What matters isn’t that different waves of immigration have a different racial composition. Rather, more established immigrant populations see economic downsides to having newer immigrant workers come in and compete for jobs. They also object to unlimited immigration on cultural grounds, having become proud of the American citizenship their group has acquired. They may even become more vociferous defenders of Americanism than whites who can trace their ancestry in the US further back.

So no, Latinos do not necessarily sympathize more with new immigrants, even when they are Latino too, than they do with Americans who want to restrict immigration. The fact that “Latino” covers an enormous range of nationalities and racial combinations only further weakens the ludicrous notion that Latinos all have one identity, one set of interests, and one preferred political party — the Democrats.

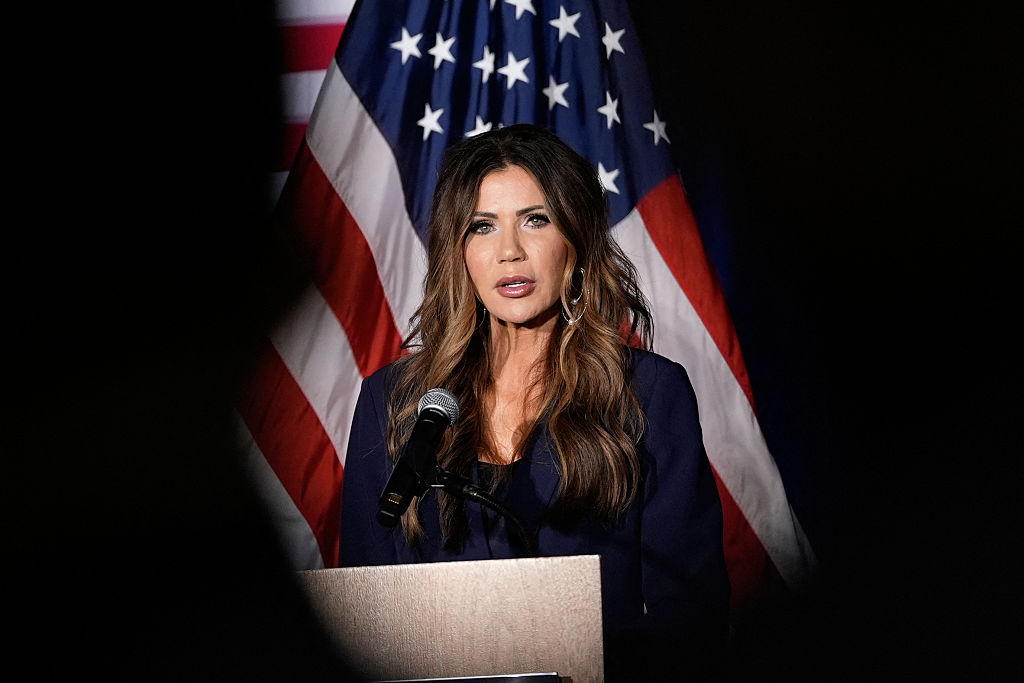

But there’s another angle too, one even more painful for multiculturalists to confront. The fact is that left-wing cultural attitudes in America, and in the West as a whole, are themselves very “European” and seem often irrelevant or repugnant to people of other cultures and racial backgrounds. White progressive Americans think of their views as being universal, but they are really very specific to their own group. White liberals believe, for example, that masculinity is “toxic” and the world needs more female leaders. They also believe that “anti-racism” requires “affirmative action” or racial quotes to give blacks in particular more representation in positions of power and prestige. White liberalism is the reason Kamala Harris was named as Joe Biden’s running mate in 2020. She wasn’t a popular politician — and as this election proved, she still isn’t. But she was the right sex and color to satisfy the requirements of white liberals.

Latinos are not white liberals. Some of them are as white as any Anglo-American, as it happens, and many are certainly liberal. But generally speaking, Latinos do not have the preoccupations characteristic of the white left in America. Some still retain an affinity for the “machismo” notable in Hispanic cultures and may have patriarchal views of women and social hierarchy that derive from Catholic traditions. They do not suffer from “white guilt.” So when the Democrats offer them Kamala Harris, a charmless politician, Latino men do not automatically take the deal. Perhaps they would vote for a woman who had outstanding merit and charisma. But Harris is a mediocrity who has advanced because of white liberal neuroses.

When the Democrats offer them Kamala Harris, a charmless politician, Latino men do not automatically take the deal

Of course, the irony applies the other way, too. Republicans generally see immigration as a threat to their political prospects, and it often is. They also have a tendency to write-off ethnic groups that are considered too tightly attached to the Democratic Party. And when Republicans do make a bid for such groups, particularly blacks and Latinos, they usually do so in the most patronizing way possible. The Republican Party has its own kind of white liberalism, but it’s less effective than the Democratic variety because Republicans are more embarrassed by it. Their awkwardness is obvious to the non-whites they court.

Trump, however, is the opposite of a white liberal. He has insouciant disregard for the racial pieties of white Americans. He doesn’t flinch from taking a hard line against immigration or using stark language to describe immigrants who commit crimes. But a tough-on-immigration and tough-on-crime stance, together with a lack of patronizing delicacy, appeals to many Latinos. And like the white ethnics before them, as new populations of Latinos have become more established, they have become more interested in making money than in being offered government benefits by Democrats. Economically and culturally, Trump appeals to a significant segment of Latinos, while Harris inspires no admiration.

There are countless other facets of Trump’s victory that will have to examined in due course. Clearly Harris’s desperate gamble on appealing to Trump’s enemies within the Republican Party, by campaigning alongside former Republican congresswoman Liz Cheney, failed miserably. Harris has been a career chameleon who by turns has presented herself as a tough-minded prosecutor as California’s attorney general, as the most progressive member of the US Senate during her time there, as a race-conscious left-wing contender for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, and finally, in this election, as a political moderate and the last hope for moderates of all parties against the extremism of Trump. Which Kamala Harris was the real one? To voters, it didn’t matte: she never won a presidential primary election in her own party before being handed the nomination when Joe Biden was forced out of the race. Left-wing Harris had no winning record, and now ‘I’m really a centrist’ Harris has none at the national level, either. Her career is over.

Trump, on the other hand, survived what would have been a career-ending defeat for anyone else in his last election, and he now becomes only the second president in American history to win non-consecutive terms. He’s remaking history, and no doubt he’s not finished rewriting the script of America’s politics, or indeed the world’s.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply