The election is less than two weeks away and early voting has begun, but we already know the winner. It’s populism.

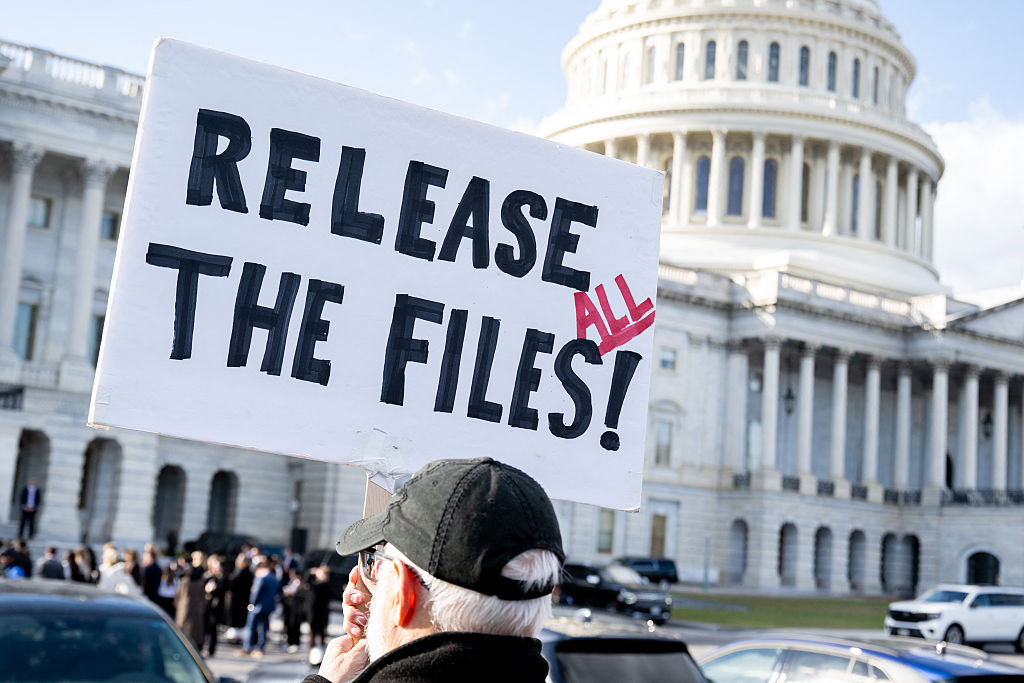

Unlike every other presidential election this century, in 2024 we’re watching a campaign in which both parties’ nominees are running on explicitly populist platforms. As a result, no matter who wins, they’ll form a government with an agenda and mandate different from the one Washington’s status quo corporatist, globalists and lobbyists prefer.

Donald Trump’s surprise victory over Hillary Clinton in 2016 was largely attributed, after the fact, to a rise in populist sentiment. Journalist Salena Zito and I wrote a book about that race, The Great Revolt, forecasting that we were witnessing a populist realignment and not a temper tantrum, as other observers surmised.

Trump’s instinctive populism is well litigated, although often obscured by the polarizing excesses of his personality, his affinity for crude shock politics and resistance to staying disciplined to a coherent argument.

In the late 1800s when populism emerged, it was mainly expressed as an anger at centralized corporate power — the banks, railroads and industrial monopolists that were screwing farmers and labor. The rise of organized labor in the first half of the twentieth century channeled that same emotion and populism remained unbroadened — all the way up to Al Gore’s failed 2000 campaign.

In this century, populism is best understood as skepticism of all centralized power — be it big business, big media, big tech or big government. Trump was the first national candidate to understand this expansion, and his defeat of Jeb Bush for the 2016 nomination gave the entire Republican Party a shotgun divorce from its unblinking country club capitalism that had long made it a mismatch for any kind of populism.

The timing for this Republican evolution could not have been worse for Democrats, in a cycle with globalist Hillary Clinton leading the ticket, after Obama-ism had transformed the liberal zeitgeist from challenging to big corporations to co-opting them. Funded heavily in their campaigns by modern-day Silicon Valley monopolists, few Democrats today even flinch at their party’s embrace of elitism and top-down power.

Candidate Joe Biden, who was once fluent in the language of populism before he was neutered by a career’s worth of Capitol cocktail parties, limped into office as the latest tool of the elite. A man whose peers were far too old to form an administration, Biden instead borrowed the talent of the activist coastal left.

Dragging through a 2024 race he was too addled to steer, Biden spent the first year of his re-election effort reading tele-prompter screeds meant only to juice the derangement his base feels toward Trump, the man. Harris, once thrust onto the ticket’s top chair, has braided a different and more coherent platform.

If you watch the veep’s ubiquitous TV ads or suffer through the word salads of her interviews, when she’s not prattling about abortion, you pick up a thick common chord: a populism that’s at least a distant cousin of Trump’s spiel on one of his good days.

Harris talks about whacking the rich and corporations with new taxes, while cutting taxes for the middle class. She pitches deductions for small businesses and a new child tax credit that Trump also endorses. She promises new federal laws to target price-gouging corporations, the villains in our inflation age, by her telling. These little vs. big narratives take up at least half of what she’s saying — never mind that they fly directly in the face of what she’s said and done for most of her career as a California elitist.

Trump, for his part, says he’ll make insurance companies pay for fertility treatments and make interest on car payments tax deductible — as if he didn’t have enough populist street cred already.

Gone are the days of GOP nominees chiding Democrats for government giveaways. Gone too are the honest liberals unafraid to say the middle class must sacrifice to redistribute to the poor.

Neither Ronald Reagan nor Paul Ryan, for that matter, would recognize the 2024 GOP platform as their ideological successor. The remaining conservative hope, a flame kindled by a too-thin band of think tank economists and columnists far removed from electoral reality, is this: With interest payments on our $35 trillion national debt now the largest single federal budget item, eventually all this free stuff will look expensive.

On the Democratic side, skeptics might assume Harris’s populism is a pose, that she’ll settle into the Obama-ism pattern of delegating the dirty work of an all-powerful state to compliant private oligopolies, forgetting her campaign pitchforks as soon as they become expendable. But the reach for populism in her time of electoral necessity is telling.

Populism’s fault is that it is not an ideology at all. It can pull the elastic in stale philosophies and yank them into a politically workable alignment, but that’s all. Populism’s strength is that it’s the only energy historically proven capable of levering that tectonic. In a world with unlimited access to information un-curated by political brahmins, the barrier to populist outbreaks now is low. The rise and durability of Trump and European populists like Italy’s Giorgia Meloni is owed partly to the turbo charge only social media provides.

Trump, and to an extent Harris, are both just transition figures. The generation of leaders coming after them will tell us which party has reconciled its beating heart to populism’s adrenal gland for the long term. Conservatives and liberals may be in a race to meld with populism without becoming disfigured by it. But for this election, we know that both sides have decided it’s populism, more than either party, that will win.

Leave a Reply