For American politicians, all wars are two-front wars. There is a hot battlefield somewhere in the Middle East or the South China Sea, and there’s a political battlefield in Washington, DC. The domestic contest is decisive. The same goes for Europe. With Joe Biden riding into the sunset and the presidential campaign drawing to a close, American interest in Ukraine is winding down, too. Europeans talking tough about “standing up” to Russia had better be prepared to do so on their own.

Donald Trump’s campaign message, muddled though it is, bodes ill for the Ukrainian war effort. His patience with this war would not extend twenty-four hours into his presidency, he warns. For J.D. Vance, Trump’s vice-presidential nominee, the Ukraine war is a mistake the United States should wash its hands of. How much of Ukrainian territory can be regained in any peace negotiations is Ukraine’s problem, not America’s. The Democratic nominee Kamala Harris has a vaguely pro-Ukraine position — one that she has barely mentioned since September. There is a reason for her silence. Americans are no longer as emotional about Ukraine as they were when Russian tanks rolled towards Kyiv in February 2022, and half the country called Russian aggression a “major threat.” This summer, a Pew Center poll found that just a third feel that way. Two weeks ago, the Wall Street Journal found that Americans prefer Trump’s Ukraine policy to Harris’s, by 50 percent to 39. The US ambassador to Nato, Julianne Smith, announced that Washington did not plan to invite Ukraine to join the organization any time soon.

The Ukrainian cause has got wrapped up in the part of Biden’s agenda that is most ruthless and least popular. In his State of the Union in March, Biden compared his situation with that of Franklin Roosevelt in 1941, when “Hitler was on the march.” His own problem was more complex, Biden boasted. He faced Hitler’s modern-day equivalents not just abroad, in the form of Putin, but also at home, in the form of his own domestic opposition. “Freedom and democracy are under attack, both at home and overseas, at the very same time,” he said. The Republicans voted to arm Ukraine last spring, but cannot be expected to do so again — not least because Democrats wove extravagant partisan narratives about Russia’s “collusion” with the 2016 Trump campaign (for which an exhaustive two-year investigation found no evidence).

With each passing week since 2022, the Ukrainian cause has become more a partisan engagement, less a national one. Republican neoconservatives like South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham have lost influence. Volodymyr Zelensky has ever fewer Republican fans. The conservative talk-show host Tucker Carlson complained that Zelensky visits Congress to solicit money “dressed like the manager of a strip club.” When Zelensky visited a munitions plant with Pennsylvania’s Democratic governor Josh Shapiro this fall, Trump spokesmen accused him of interfering in the presidential election.

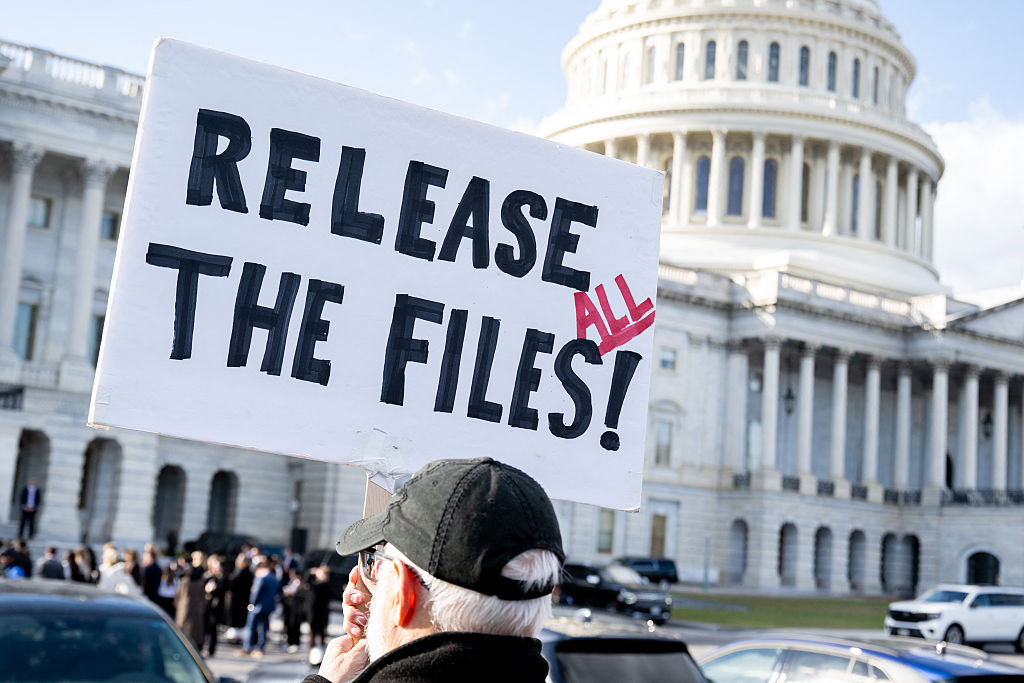

Since the summer, Ukraine has been tied into a broader complex of issues that drove Biden from the presidential race. Defending Ukraine is costing the US hundreds of billions of dollars at a time when its border with Mexico has been left undefended. As in Britain, America’s Ukraine policy has been carried out through a campaign of war propaganda extravagant enough to undermine the government’s reputation for truth-telling more generally. Ukraine, probably the most corrupt country on the European landmass, is presented to the public as a model democracy. Government pronouncements wildly exaggerate the ratio of Russian to Ukrainian casualties. Officials echo Keir Starmer’s judgment that Russia is using its conscripts as “bits of meat to fling into the grinder,” as if Ukraine is not doing the same. Frequent allegations that Russia uses “misinformation” to “destabilize” and “divide” our democracy are repurposed for stifling domestic dissent, and discredit the notion of disagreement itself.

The Ukraine war has left the West at high risk of a world conflagration, at a time when the public has little reason to trust that the President has the mental acuity to judge the signals right, or that it is even he who is doing the judging. The Biden administration has been run, in the President’s cognitive absence, by a junta of special interests. In September the US and UK considered using ATACMS and Storm Shadow missiles to strike deep into Russia. Such a shift in policy posed insane risks, which neither government (particularly the UK’s, it must be said) appeared to understand.

The problem is not that the West was butting into Ukraine’s launch decisions. The problem is that Ukraine cannot launch these missiles on its own. They require western radar and targeting. Their use would thus have been a direct NATO attack on Russia, which remains the world’s most heavily armed nuclear power. Yes, the West has participated in missile attacks on Crimea — not terribly wise, either, but at least its insistence that Crimea is part of Ukraine provides it with a fig leaf under international law. It remains a dangerous situation, which the Zelensky government has every incentive to escalate, particularly as its own military loses momentum on the battlefield.

The Ukraine war does not appear in the same light at the end of this presidential campaign as it did at the beginning. Be it Harris or Trump, the next president will find the domestic pressure to scale back US involvement irresistible. Harris’s foreign policy team includes a number of veterans of the Obama administration. Obama helped to calm the Russia-Ukraine conflict, mostly by withholding arms, a decade ago. The region was at peace under Trump, too. Not because he threw his weight around, as he falsely boasts, but because his administration was admirably disinclined to internationalist hubris and human rights messianism. History will liken Biden’s foreign policy to that of George W. Bush, another strange interlude when a mood of world-shaping ideological fanaticism briefly overtook the traditionally pragmatic Anglophone powers.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply