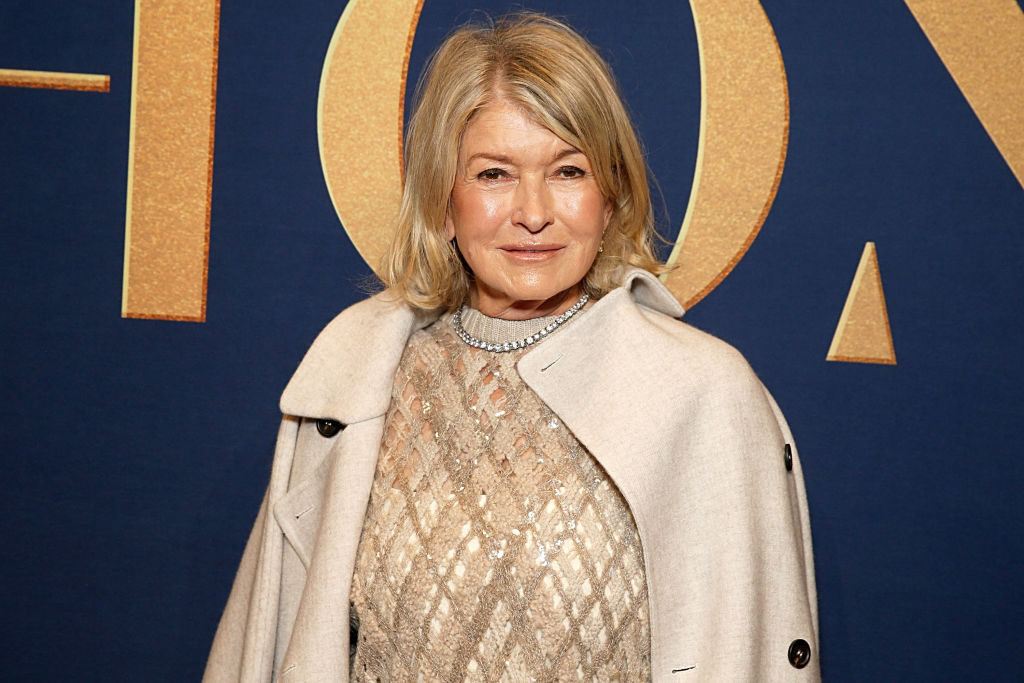

Homemaker extraordinaire Martha Stewart has a fascinating new documentary about her life out on Netflix. The nearly two-hour film features narration from Martha herself about her childhood, her rise to fame, her marriage and the insider trading case that nearly destroyed her career. It’s worth a watch if you’re trying to get inspired ahead of your Thanksgiving celebrations tomorrow or if you just want to better understand the mindset of the perfection-driven television, magazine and homeware mogul.

As I watched the documentary, though, I was mostly surprised at the parallels between the societal perception of Martha’s homemaking skills at the height or her popularity and the modern discourse about “tradwives.”

To be clear, Martha is not a “tradwife” under the commonly understood definition of the term. She does not live by traditional gender roles, prioritized her high-powered career and has expressed an aversion to house dresses and aprons. In fact, Martha has publicly spoken out against the viral trend, even as she acknowledges that she enjoys watching some tradwife content: “I hate it so much… I don’t like the name.”

Martha is more of a “girlboss,” to use the cringy millennial term, but had feminine hobbies that she leveraged into a successful career as a home and lifestyle influencer. Tradwives, comparatively, have occupations as homemakers. However both face many of the same societal critiques.

When Martha was building her empire, more women than ever were in the workforce and thus were prioritizing convenience over quality. Martha, in contrast, believed in the importance of keeping a beautiful home, maintaining a functional yet elegant garden and making delicious, elaborate meals for her family and guests. She was often accused of selling an “unattainable” lifestyle and making perfection seem easy, of representing an upper class fantasy. Isn’t that the same type of negativity often thrown at tradwife influencers like Ballerina Farm, Nara Smith, Estee Williams and Aria Smith?

Even if women didn’t always have the time to recreate Martha’s dreamy tablescapes or homegrown bouquets, there’s a reason why Martha’s content resonated with them just as much as tradwife videos do now. They are meant to be aspirational, not disparaging. We’d like to have a cleaner house, a home cooked meal every night, fresh bread on Sundays. Why would we be angry at the person who shows us what is possible and how to get there? We may never be as a good as Martha, but if she helps us get 5 or 10 percent better, take it as a win. And if that makes you feel bad, then that’s on you, not the person on your television or phone screen.

Eye-color changing surgeries gain popularity

I was reading the Wall Street Journal this week and discovered that a new cosmetic surgery is surging in popularity. Gone are the days of color contacts: doctors say more and more patients are coming to them in the hopes of permanently changing the color of their eyes, a procedure that costs about $12,000.

I’ve written in this newsletter about the damaging side effects of plastic surgeries and other less invasive procedures like Botox and fillers that are driven by increased social media use, particularly among young women. Consider the eye color-changing surgery, known as keratopigmentation, an extreme example. The WSJ describes the procedure:

Dr. Alexander Movshovich used a laser to cut donut-like tunnels into his corneas, the clear outermost layer. The surgeon used a tool to widen the tunnels before filling them with dye. The procedure, known as keratopigmentation or corneal tattooing, was completed in about a half-hour. The effect was immediate.

The treatment was developed to treat people with diseased or otherwise defective eyes, where the potential benefits probably outweigh the risks. When done for cosmetic reasons, keratopigmentation, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, carries serious risk of vision loss, light sensitivity, and bacterial or fungal infection. Surgeons who perform cosmetic keratopigmentation say the risks are overhyped, pointing to a 2021 study wherein twelve out of forty patients complained of temporary light sensitivity. Five said the pigment faded or changed in color.

I wouldn’t rely on a study of a mere forty people to justify risking my eyesight for the purpose of changing my natural eye color, but that’s just me. Mark me down once again as deeply concerned about the lengths to which humans will go to satisfy their vanity.

Leave a Reply