When I visited New York for the first time in a decade recently, one of its most famous living writers, Paul Auster, died on the day I arrived. This was not, I hope, anything to do with my presence in the city he spent decades memorializing; he had been suffering from terminal cancer for a considerable time. Yet as I sat at my desk at the first hotel I was visiting, the Frederick in Tribeca — a comfortable and well-located spot, let down slightly by its surly and unhelpful staff, but redeemed by stylish touches like a tiled map of nineteenth-century Manhattan built into the well-appointed shower — and started to write a tribute to Auster for our website, it made me wonder what, exactly, I was trying to find out about literary New York. Was I exploring its distinguished past? Or its current state? Or even, dare I say it, looking to its future?

I was pondering all this even before I arrived, as I flew in from London via Dublin on Aer Lingus. (A tip for anyone coming to the city who isn’t a US resident — you can go through US immigration in Dublin or Shannon infinitely quicker than at JFK, even allowing for a change of planes.) I’d inveigled myself into the business cabin and was highly impressed by the service, not least the comfortable seat, decent quality food and wines and wide choice of entertainment. But as I submerged myself, semi-somnolently, in the dire Saltburn, the thought kept running through my head: what am I going to discover there?

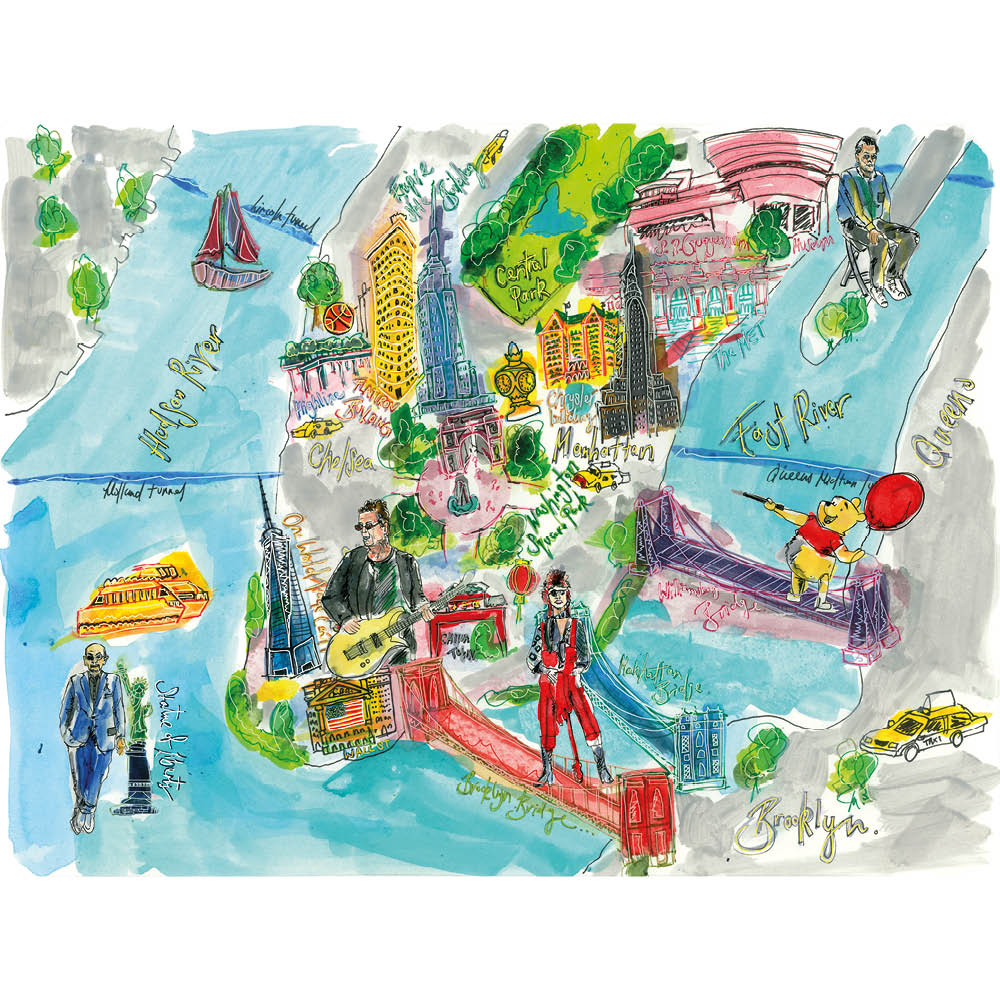

New York is a city built on the written word. A first-day visit to the New York Public Library confirmed this immediately. The Polonsky Exhibition of Treasures shows the remnants of Shelley’s skull and the toys that inspired A.A. Milne to write Winnie the Pooh, in a nod to the city’s British origins, even as more contemporary displays focus on Tennessee Williams, LGBTQ protest documents and a page from one of James Baldwin’s manuscripts. It’s eclectic, challenging, slyly controversial in places — some might argue that some of the writers, naming no names, are less deserving of a place in this particular company than others — and the incongruity between the grand marble halls of the NYPL and some of the anger and pain to be found therein made for an intriguing combination. But I knew that I was only just getting started.

Over martinis, oysters and steaks at one of the city’s finest steak restaurants, Hawksmoor, I confided in this magazine’s editor about my quest for discovering what a New York writer was. We made short work of excellent fried Louisiana shrimp and Maine lobster as we discussed the passing of Auster and the furore the adopted New York writer, Salman Rushdie, was causing with his memoir about his near-fatal stabbing, Knife, and as we took on a very fine bottle of Malbec to accompany the tomahawk steak — appropriately enough — that we were sharing for a main, I asked Zack what he thought the point of being a writer in Manhattan was. His answer was gnomic in its simplicity and Confucian in its wisdom. “To be a writer here’s much the same as being a writer anywhere else. The first prerequisite is that you’ve got to write.”

Brave words, I thought, and as I left the Frederick, I walked around the corner to the newly opened Warren Street Hotel, in search of inspiration. It’s run by the peerless Firmdale group, who not only have the Crosby Street and Whitby properties elsewhere in the city, but a coterie of high-end establishments in London, including the Charlotte Street Hotel, Soho Hotel and that haunt of celebrities and fame-seekers alike, the Ham Yard. Their parties are legendary for attracting the beau monde. I still remember meeting Salman Rushdie at one of the Soho Hotel’s innumerable book launches about fifteen years ago, making small talk based on the slightest previous acquaintance (we’d met at the Magic Roundabout premiere the year before, and discussed magic realism in cinema while his son played in a ball park) and asking him what he was doing later that evening, to which he replied, magisterially, “I’m having dinner with Lou Reed and David Bowie.”

Well, that was me told. Bowie was, of course, one of New York’s most famous adopted sons, and even if his fame lay in music rather than the written word, I’m sure he would have enjoyed the short walk over from his SoHo (the US one) apartment to the Warren Street, whether for a sumptuous afternoon tea, a sublime dinner in the English-accented restaurant (although given that he was famously latterly a teetotaler, he would have eschewed the fine Old Fashioned and excellent bottle of Château Latour-Martillac that I shared with the hotel’s suave and charming manager Nick, another Englishman abroad) or for a few nights’ stay in one of the beautifully appointed suites on the upper floors, some of which even contain private terraces. It made for a sublime place to relax, and write, and think, and I could have stayed there considerably longer than the two nights I did.

But don’t think for a moment that my quest was over. I solicited a writer friend to join me for dinner the next evening at one of Midtown’s most salubrious and acclaimed spots, the Michelin-starred Le Jardinier, which operates at a supremely high level under the influence of Joël Robuchon protégé Alain Verzeroli. Over a five-course extravaganza of poached lobster with polenta, fine white asparagus and the best duck that I can remember having anywhere, we discussed literature and New York. Is there, I ventured to ask over the superb wine pairings, offered with aplomb by the charming — if temporarily teetotal — sommelier, something in the city that has inspired everyone from Rushdie and Baldwin to Auster and Edith Wharton? My companion shrugged as he sipped his Vespres Riviera cocktail. “The trick about writing in New York is to confound expectations. Don’t come to this city expecting to get all the answers straight away.”

This was all too cryptic for me, so I upped the ante. I checked into one of the city’s longest-established and most literary hotels, the Peninsula, and gazed out over Fifth Avenue from my twentieth-floor eyrie. In search of inspiration, I decided to head to the nearby Morgan Library, twenty or so blocks away, to see what might be what. I had the good fortune to fall in with a couple of supremely erudite and wonderfully gossipy curators there, who, in addition to giving me tips on what to see (and what to avoid) on Broadway and some sublime history about the collection’s first librarian, Belle da Costa Greene — who, I was informed, “flirted for Manhattan” — filled me in on the next stage in my quest. “Everybody here who writes has come from somewhere else, whether geographically or intellectually. It’s a melting pot. And the litera- ture it produces reflects this.”

As luck would have it, I was soon to find my own slice of Manhattan surrealism. I dined solo that night at Alain Ducasse’s restaurant Benoit, armed only with my notebook and people-watching skills. Everyone there seemed to be going ape for the sublime traditional French cuisine, but I was smilingly told that I would be offered a special menu of the house specialties, which consisted solely of Italian dish after Italian dish. Vitello tonnato, spinach ravioli, spaghetti with clams — all were sublime (to say nothing of the best tiramisù that I can remember eating), and the wine was devastatingly good, but what was going on? Was I in a situationist farce? All was revealed when the chef Alberto Marcolongo came out. When I asked precisely why he’d recommended these dishes in a French bistro, he smiled and said, “Because I’m Italian.”

This, more than any other experience I had, seemed to sum up the delights and contradictions of New York. Returning to the Peninsula, where my absurdly comfortable room sent me to sleep before I could do more than make the most cursory notes about my evening, I became lost in contemplation of the city’s unique sensibility. It is a place where every panhandler on the subway prides himself in being able to bark out one-liners, and where everyone from Dorothy Parker to Tom Wolfe excelled at capturing the spirit of a place where it isn’t enough just to be clever, but you have to be clever, fast, whether it’s coming back with a devastating put-down or, indeed, upending expectations by serving an all-Italian menu in a French restaurant.

I was still pondering this the next day when I took a reluctant leave of the Peninsula — for my money, the most hospitable and welcoming of all the city’s grand and historic hotels, and with a notable reputation for having hosted most of its authors during its current and former incarnation as the Gotham. But there was just time to enjoy brunch before I caught a flight back from JFK, and as I enjoyed sublime bellinis and the best espresso martini I’d had since I arrived in the city – a perfect pick-me-up before a long journey home — I asked the sommelier what he thought made New York such a magnet for writers. He smiled, and cited Colson Whitehead, who wrote at the start of The Colossus of New York that he pitied the native New Yorker, because they were ruined for anywhere else.

It was all I could do to smile, agree, knock back the last dregs of my drink and rush outside to the waiting cab. The imported New Yorker, whether for a week or a lifetime, always looks in on the city from afar. They have the writer’s detachment from its joys and sorrows, its secrets and its pomp. To quote one of the city’s great sons Thomas Wolfe, himself from North Carolina, “One belongs to New York instantly, one belongs to it as much in five minutes as in five years.” But to have been born there and live there all your life? It is hard to imagine any author having a greater privilege, and I envy them that.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply