It was stiflingly hot in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. I was exploring the eastern Galápagos Islands, living cheek-by-jowl on a former casino ship with a cast of characters plucked straight from a murder mystery novel: a former British supermodel, an Ecuadorian presidential candidate, the ex-drummer of a band who once supported the Who and an influencer couple who looked like they had stumbled off the set of Triangle of Sadness.

The stars of the show – and boy did they know it –were the sea lions

While the trip had all the ingredients to cook up an irresistible whodunit, I was not just there to inspect the wildlife on board but to observe the wildlife off it. The Galápagos Islands are a volcanic archipelago of 21 islands 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador, and they are rightly considered to be one of the greatest national parks on our planet. The islands are home to some 4,000 species, around 40 percent of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

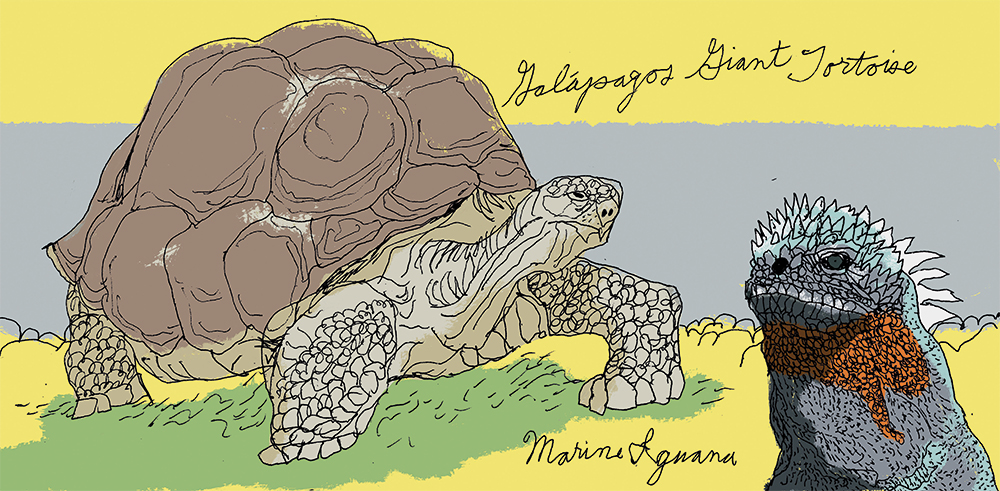

It is almost 500 years since the accidental discovery of these islands by Tomás de Berlanga in 1535. Berlanga was the bishop of Panama and he was tasked with travelling to Peru to mediate a dispute between Francisco Pizarro and the Spanish Crown. Midway through his journey, wild winds knocked him off course and he drifted towards an unknown island. Berlanga and his crew arrived cotton-mouthed, so parched they began to drink cactus water. Soon, they came across giant tortoises, sea lions and marine iguanas. “Like serpents!” Berlanga wrote to the Spanish king, describing his surreal encounter. “And so silly they don’t know how to flee.”

Three centuries later, in 1835, a 22-year-old naturalist named Charles Darwin sailed to the islands on HMS Beagle after completing a surveying mission of the South American coast. He was fascinated by the volcanic nature of the islands but, like Berlanga, was hardly enamored. “Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance,” he recorded. But during his five weeks on the islands, living among fluttering finches and prickly pear cacti, Darwin’s theories of evolution began to take shape. In 1859, On the Origin of Species was published: we know it as the foundation of evolutionary biology.

I confess that I, too, was guilty of judging the islands too quickly. On first glance, many of them – with their harsh, rugged and sun-scorched terrain – can seem uninviting, even post-apocalyptic. But the magic of these islands is that once you get closer, a whole spectacle begins.

A trip to the Galápagos is, of course, a far more curated and bureaucratic affair than what would have taken place in Berlanga and Darwin’s day. The archipelago is a UNESCO World Heritage site and national park, so it is subject to strict conservation laws. The Ecuadorian government, along with various international organizations, works tirelessly to protect this fragile ecosystem, particularly as tourism increases.

Visitors must: obtain a transit control card, travel with an authorized guide, stay on marked trails and never feed or touch the animals. “Please do not touch the sea lions!” the guides – long-suffering but commendably patient – repeated, even as the sea lions, coquettish as ever with their cartoonish eyes, wobbled up to our ankles. It often felt like the wildlife had more freedom on these islands than we did.

Our voyage on yacht La Pinta looped east from Baltra to Santa Fé and San Cristóbal before swerving south to Española and Punta Suárez. As we boarded the dinghy to reach the islands themselves, a fleet of frigatebirds – known as the “pirates” of the sky – heralded our arrival, slicing through the wind with their black plumage and forked tails. A trip to the Galápagos Islands is pure theater. Each island is a different stage; each animal plays a different part. Visitors merely sit back and watch the show.

The overture began on South Plaza, one of the smallest islands in the archipelago, known for its fiery red carpetweed. It changes to purple, green and orange as the seasons shift. Creeping through the color were dinosaur-like marine iguanas, a remarkable example of natural selection and the only seafaring lizard in the world. South Plaza is also the place to spot the rare marine-land hybrid iguana, a mishmash of species with distinctive black coloring and long yellow stripes believed to be able to survive in both marine and terrestrial environments.

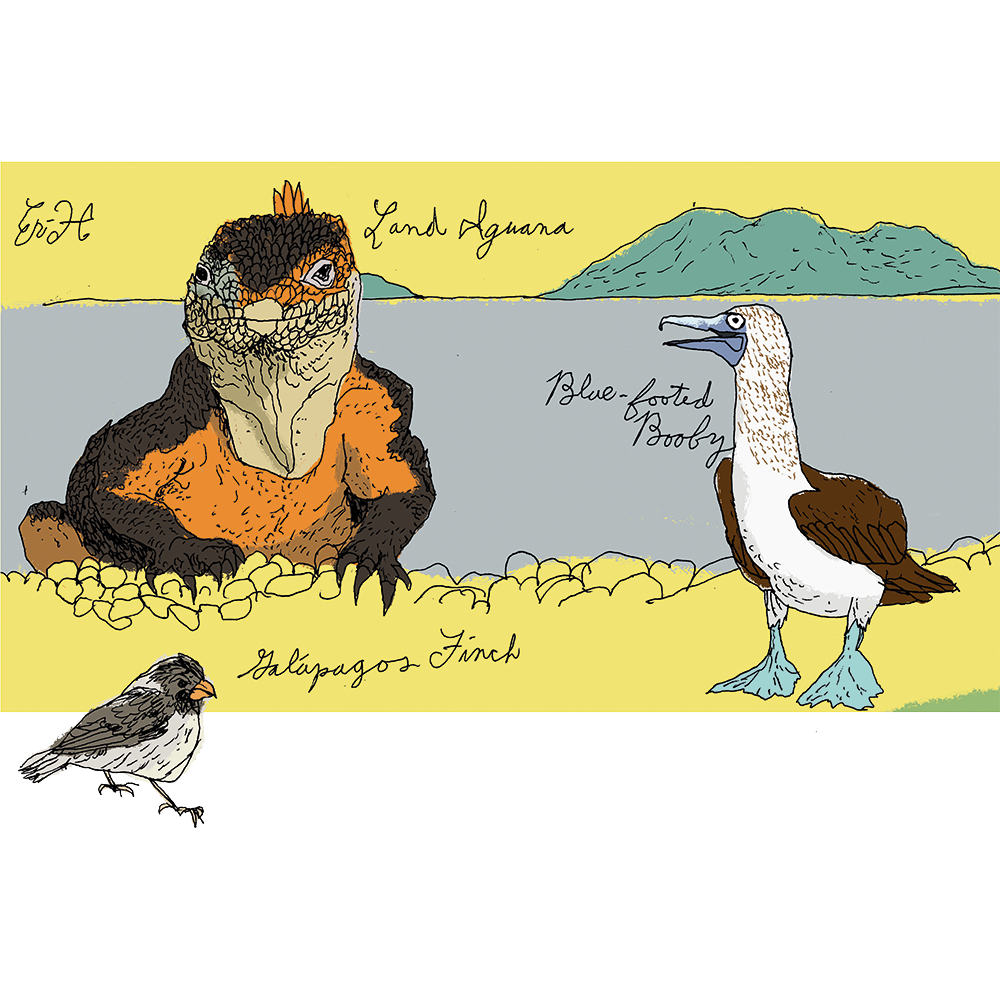

Next came Santa Fé (or Barrington) Island, one of the oldest in the archipelago. Unlike its neighbors, its formation stems from geological uplift rather than a volcanic eruption, creating a relatively flat terrain punctuated with prickly pear forests and crab-covered rocks. The island teemed with endemic species: the Santa Fé land iguana, Darwin’s finches, Galápagos hawks and swallow-tailed gulls, whose red-rimmed eyes made them look as though they hadn’t slept since 1535.

The stars of the show – and boy did they know it – were the sea lions, who sprawled across the rocks like Titian’s “Venus of Urbino.” If they weren’t basking in the sun they were lolloping onshore, flapping their fins like quarreling siblings and barking with an emphysemic honk. They showed no fear and were consummate performers. Thespians of the highest pedigree.

The easternmost island is San Cristóbal, which is composed of extinct volcanoes and lava fields. Darwin noted the remarkable tameness of the animals during his visit – and so did we. As we wound our way up a trail, it felt like the show’s crescendo had begun when we finally glimpsed the comical feet of a blue-footed booby. “Look! Love is in the air,” Pancho, our peppy, silver-haired naturalist exclaimed. A male frigatebird was just ahead of the booby, inflating his bright red throat pouch as if it were a whoopee cushion. Pancho explained that once puffed up – a process that can take half an hour – the males begin their mating call: shaking their wings, swaying their heads and drumming their bills on the pouch. Females hover above, judging the performance. “It’s a crazy time to be in the Galápagos,” Pancho grinned. “This is one of the best mating rituals to see.” It was 95 degrees and not yet 10 a.m., but for these frigatebirds, the action had begun.

Our curtain call came on Española Island, the southernmost point in the archipelago and the primary nesting site for the world’s entire population of waved albatrosses. Here we found “Christmas iguanas” – marine iguanas colored festive red and green – and colonies of wheeling, squawking seabirds. On the return from the trail, we paused to look at a Galápagos hawk’s nest: the apex predator of the islands. “Nature is full of surprises!” Pancho beamed once more, explaining that the female hawk mates with multiple males, leaving paternity an open question – the Mamma Mia! of the bird world.

The trip felt like one big open-air opera. Berlanga and Darwin may have escaped the constraints of modern-day tourism, but the wildness they encountered here remains unchanged by time. This is nature in its purest form: unscripted, unfiltered, unchained.

Saffron visited Ecuador and the Galápagos lslands with Metropolitan Touring. Yacht La Pinta offers four- and six-night itineraries around the islands with luxury cabins starting from US $5,870.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply