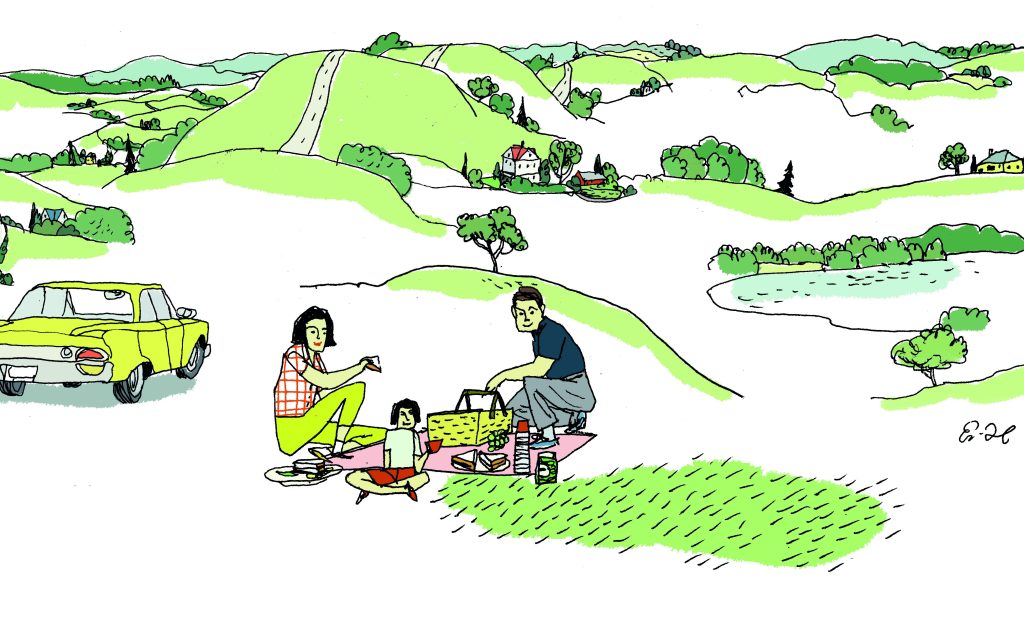

Signs announcing roadside picnic tables once peppered America’s secondary roads and highways. Or so we call those byways now. Before the limited-access interstate system arrived in the 1960s, these roads were primary. America then was laced with a tangle of serviceable two-lane, hard-surfaced highways. Look at an old oil-company roadmap, if you can find one, to get the idea. Some roads were federal, some state, but all were emphatically open-access: get on anywhere, pull over wherever you like. They led through cities and towns, not around them; they traversed the countryside more than they cut through it. They required two-hands-on-the-wheel alertness in drivers, who got to know and respect the lay of the landscape.

“Roadside Table One Mile” signs invited you to pull over, switch off the ignition, stretch your legs, uncork that thermos of coffee and have lunch. They were as common, and as eagerly watched-for, as the standardized signage that guides us to branded “services” along the interstates today: “Food Next Exit / McDonalds, Burger King, Cracker Barrel.” Oh boy.

Compared to anywhere else in the world, America was enormously rich in the 1950s, though grown-ups then could still remember the time, not far back, when it wasn’t. They were the last American generation to have experienced scarcity as a fact of life, and they were slow to shed frugal habits learned in depression and war. Roadside tables, and the style of eating experienced there, were leftovers from that time. Through the first two postwar decades, Americans ate outside the home far less than they do now. Restaurants were fewer, sub-restaurant fast-food franchises yet unknown. Saving, not spending, was still a strong cultural instinct and eating out was relatively expensive. So you packed your own vittles from home, replenished from a grocery store en route if necessary. Do it yourself.

For middle- or working-class families, “vacation” meant loading up the family’s one and only car with suitcases and picnic supplies and heading off — to the beach or the mountains or to the grandparents’ house. Cars were big and roomy and seldom air-conditioned, with plenty of room for two parents and two brothers, with space reserved in the trunk, or in the well behind the second seat if it was a station wagon, for some simple groceries and a cooler.

Millions of American families have their own memories of those journeys and the road fare that accompanied them. Ours are conditioned by facts of short time and long distance. Between South Carolina and Virginia, where we grew up, and our father’s family farm in the northwestern corner of North Dakota stretched some 2,000 miles of two-lane highway: three days minimum of roadside tables each way. Coolers then were metal, treasure-chest-shaped affairs with hinged lids, or round like a small barrel. Everyone knew the phrase “Scotch Cooler”: it wasn’t an adult beverage but a barrel cooler with trademark tartan decoration. Like the suitcases in the attic, the cooler came down from the shelf in the garage, to be wiped down and readied with reverence. The morning of departure, ice cubes from the small freezer compartment of the kitchen fridge were tumbled into the bottom, followed by small cans of fruit juice, V-8 and orange-pineapple. Bottled water was unheard of and soft drinks were a special treat, bought for a dime in glass bottles from a gas station vending machine. At the top of the cooler was a fitted metal tray that suspended food to be kept cool and dry: hardboiled eggs, sliced bologna or some other luncheon meat (maybe cold chicken the first day out). There were green grapes, a jar of French’s yellow mustard, a knife for spreading, a church-key for opening. If mother had made sandwiches ahead of time, they were, in that pre-baggie era, wrapped in cellophane. A paper grocery bag held white Sunbeam or Wonder Bread, a box of Triscuits, paper napkins, picnic-size salt and pepper for the eggs while they lasted.

The roadside tables where we stopped to partake (one did not eat meals in the car) were public places, which in our mother’s book required a tablecloth, red- or blue-checked usually, vigorously shaken out when lunch was finished and folded up for the next day. Trash, such as it was, went in the oil-drum bin provided. An ice cream from a roadside stand, if one presented itself, might be offered as afternoon refreshment.

Taste, like our other senses, responds to contrast. Too much of a good thing, they say, dulls the appetite for it. We bore easily. Our simple roadside repasts thus served another purpose, keying-up our anticipation of the fuller feasts that awaited us, either that same evening at a Howard Johnson’s or suchlike family restaurant, or at journey’s end. For us, this meant the farm and our farm relatives, whose way of life — and eating — seemed so different from ours.

Less sophisticated than our New York-born mother who was a cook with culinary ambitions and an early subscriber to Gourmet magazine to prove it, our grandmother and our aunts were just plain cooks in a rural American tradition known for wholesomeness, if not variety. Aunt Olga’s roast beef was “sourced,” as we would say pretentiously today, from the herd of white-faced corn-fattened Herefords you could see out the kitchen window. Bread was white and came from her own oven, sliced thick and eaten with butter. Norwegian lefse, slathered with butter too and rolled up with brown sugar, would never have translated back east. Salad meant iceberg lettuce turned white with sour cream and vinegar. Vanilla — and vanilla only — ice cream, scooped not into dessert but cereal bowls, came from a neighbor’s creamery in town. None of it was like the food we were used to. Anticipation for it spurred us on through many a westbound roadside lunch. Memory of it kept us going all the way home.

The simplicity of roadside tables set a certain tone. They announced, “Now we’re traveling.” Things are different now, both from what we knew back home and what awaited us up ahead. It was our own, admittedly mild, version of life on the open road. Simple lunches enjoyed outside were like a daily picnic, something that normally was an infrequent treat. And those tables, we should note, were not secluded back in some “planned” and landscaped picnic area. There were, literally, roadside, the whoosh of traffic close at hand, which, believe it or not, could bring a thrill. Tastes, sounds and sights conspired to leave no doubt: we were on our way.

The interstates, which have so speeded travel times and without which many would find driving unthinkable, have also stolen our experience of pretty much anything that lies between our points of departure and arrival. The roadside table is one casualty. A few remain, although, as critics might say, the quality is uneven. Some are fine, probably more forlorn. It is good to approach with a spirit of adventure. This much is certain: seeking one out and laying out the family’s lunch will slow you down. Delay or delight? The choice is yours.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2023 World edition.