Chablis has the paradoxical distinction of being at once one of the most famous and least well known of French wines. Hugh Johnson opined that it is “one of the world’s most under-estimated treasures.” I agree.

We say that Chablis is Burgundy, but, situated on the Serein River some 100 miles southeast of Paris, Chablis is nearly 100 miles north of Beaune. Perhaps we can say that it is the Hadrian’s Wall of Burgundy. Hadrian’s bit of Britain was part of the Roman Empire, but no one would confuse it with Rome.

The climate in Chablis is markedly different from and less forgiving than that of the Côte-d’Or: chillier and windier. Think of Auden’s poem, “Roman Wall Blues”: “The rain comes pattering out of the sky, / I’m a Wall soldier, I don’t know why.”

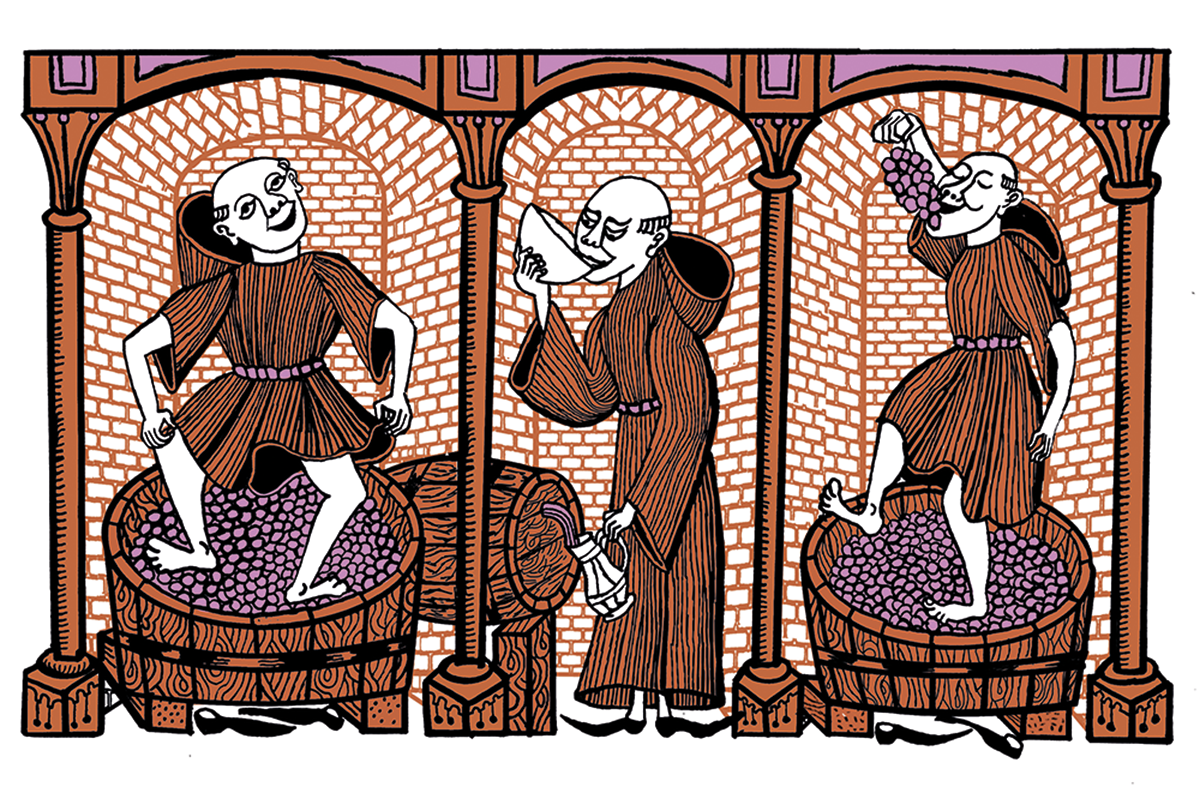

The soil is distinctive in Chablis, too. The area sits on top of an ancient pudding of limestone, clay and fossilized oyster shells called the Kimmeridgian marl. (Remember the word “marl.” It will be on the test.) The basin extends across the English Channel to Dorset and is at once demanding and generous to the vine. Unlike the rain that falls in southern Burgundy, which drains into the Mediterranean, the rain that falls in Chablis is part of the Seine River basin and drains into the North Sea. Roots must burrow deep, deep to reach the rapidly draining water, but the journey imparts a rich minerality that the French describe as “goût de pierre à fusil,” the “taste of gunflint.”

Well, that’s the foundation. Like its famous cousins down south, Chablis is 100 percent Chardonnay, but a hardy variety called “Beaunois,” “from Beaune.” “Chardonnay,” one wine writer observes, “responds to its cold terroir of limestone clay with flavors no one can reproduce in easier… wine-growing conditions — quite different, even from those of the rest of Burgundy to the south.” Indeed. No one would ever mistake a Chablis for, say, a Montrachet or Corton-Charlemagne. Less butter, more flint. But that is just a start.

Chablis is renowned for its consistency. Its wines can be divided into four types. At the lower end of price, richness and complexity are Petit Chablis and Chablis, of which there is a great abundance.

Then there are about eighty climats designated “Premier Cru,” of which my favorite is Fourchaume, bottled by several vintners. Where I live, these can be had for about $35-$70 and are fresh, citrusy and slightly floral. Remember those fossilized oyster shells? A dozen of their descendants will go nicely for lunch with a bottle (or two if you have company).

More select are the seven Grand Cru wines, which account for only about 1 percent of the wine produced in Chablis. They are clustered together on a southwest-facing slope just to the east of the town of Chablis. Opinions vary about which is the best. Some plump for Valmur, some for Vaudésir. Many people — and it’s where I put my vote — regard Les Clos as consistently the best of the Grand Cru climats. At sixty-six acres, it is also the largest.

The wines are succulent but taut, with a complex depth of flavors that dance upon the palate. There is something slightly majestic about the best Chablis, a quality Hugh Johnson evoked when he said that the wine can “taste important, strong, almost immortal.”

The most fabled, and also by a large factor the most expensive, of the Grand Cru Les Clos is Domaine François Raveneau. Production is tiny, and good vintages with a little age are generally selling for four figures, not three. I have never had one. If you snag a bottle, please text me and I’ll pop right over with some of those oysters or a tub of Beluga.

Several other producers make excellent wines. My favorites are those made by Christian Moreau, who has two vineyards in Les Clos, as well as Grand Cru vineyards in Valmur, Vaudésir and Blanchot. He also owns a premier cru (Vaillon) and untitled Chablis and Petit Chablis. I have had several bottles of his 2015, 2018 and 2019 Les Clos (about $150 in a shop), and I had the pleasure of meeting him over a bottle of the 2019 with some friends at my new favorite New York restaurant, Gotham at 12 East 12th Street.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.