Batavia, New York

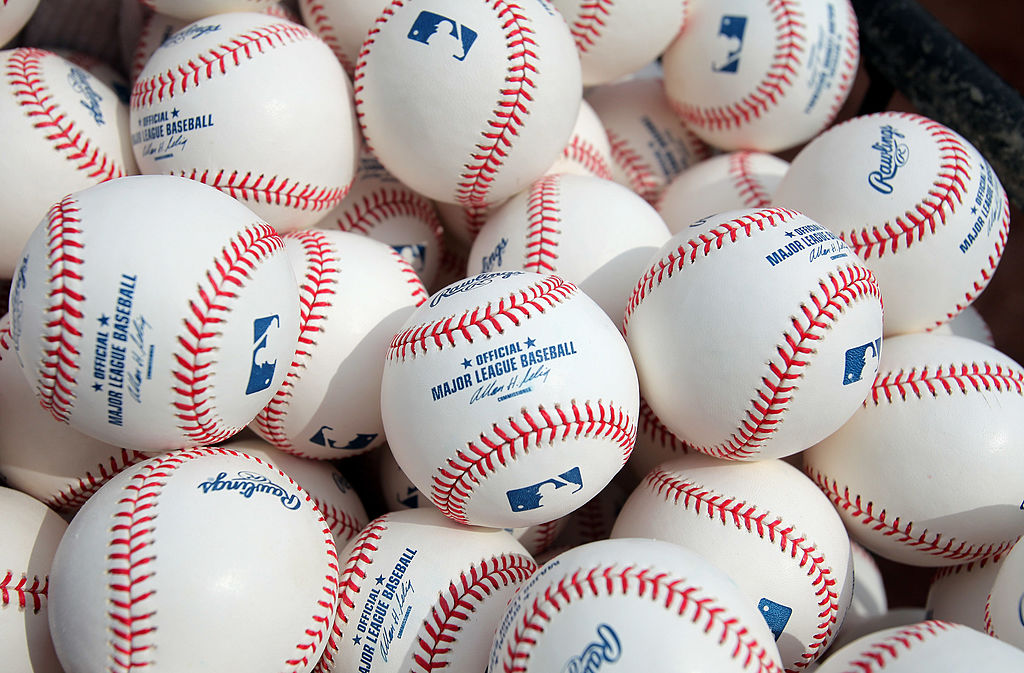

‘Tis spring, and if a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love, as Tennyson opined, an older man’s reveries turn — no, not to lawn-mowing — to baseball.

Not, in my case, to the grotesque parody of the American game on display in the major leagues, with their automatic extra-inning runners and TV timeouts and $100-plus tickets, but to the sandlot, the high school or college field, the amateur and independent and minor-league ballparks built on a human scale and played in with joy, even in error, by mere mortals.

Every year at this time I also order a cheap Detroit Tigers decal or pennant to place across the grave of Vince Maney, the only boy from my hometown ever to play a game of major-league baseball — and that’s all he played, one single game, and it took him almost a century to get credit for it.

That one-game detail calls to mind Moonlight Graham in W.P. Kinsella’s novel Shoeless Joe, which was rendered cinematically in the sweetly sentimental if sometimes eye-rollingly annoying Field of Dreams. (Is there a more excruciatingly deck-stacked scene in movies than the PTA debate over book-banning? Amy Madigan’s self-righteous anti-ban harangue is the fantasy of every smug and somewhat-above-average-intelligence child of the provinces who has felt herself better than the earthbound clodhoppers who surround her.)

Moonlight Graham — who really existed — was the town doctor of Chisholm, Minnesota. His career consisted of one inning played in one game for the 1905 New York Giants — until novelist Kinsella revived it in an Iowa cornfield.

In the film, Doc Graham is portrayed by the reliably repulsive Burt Lancaster, whom I cannot watch without recalling the remark by procurer-to-the-stars Mickey Knox: “You have any idea how hard it is to get Burt Lancaster blown every night of the week?”

We have no such tomfoolery in Batavia, New York, so let me tell you the story of Vince Maney. He was a twenty-five-year-old Batavia boy who was toiling at the Iroquois Iron Works in Philadelphia. For recreation he played semi-pro baseball. He may have fantasized about playing in the majors, but that was about as likely as getting a date with Mary Pickford.

Then Ty Cobb blew his top. The hot-tempered Detroit Tigers star stormed the stands in New York’s Hilltop Park to beat the guff out of a heckler. When American League president Ban Johnson suspended Cobb for his outburst, his Tiger teammates struck in solidarity. In response, Johnson threatened to fine Tigers owner Frank Navin if Detroit did not field a team for its upcoming game in the City of Brotherly Love against the Philadelphia Athletics.

A hastily assembled Tigers squad recruited off the streets of Philadelphia took the field at Shibe Park on May 18, 1912. Aloysius Travers, a future Jesuit priest, was on the mound for the ragtag team. The padre pitched a complete game — but lost, 24-2. The regulars returned for the next Tigers game, but the memory of this one lasted a lifetime for its participants.

Playing shortstop for the motley Tigers was… well, here it gets complicated. For years, the baseball record books listed him as forty-one-year-old Patrick Meaney, the oldest rookie to break into the majors until forty-two-year-old Satchel Paige joined Cleveland in 1948.

But as the millennium dawned, local historian Bill Dougherty, determined to do his Irish homeboy justice, convinced the keepers of baseball records that the shortstop was actually Vince Maney. The evidence? A photograph of Vince, in uniform, standing with Detroit manager Hughie Jennings, and a letter from Vince to his brother excitedly relating, “I played shortstop and had more fun than you can imagine. Of course it was a big defeat for us, but they paid us fifteen dollars for a couple of hours’ work and I was satisfied to be able to say that I had played against the world champions. I had three putouts, three assists, one error and no hits.”

Vince Maney, having tasted glory, came back to Batavia after serving in the World War One. He founded an insurance company bearing his last name and died in 1952. I would’ve liked to have known him, but I was just a kid. Nah, I wasn’t even close to being born yet — just wanted to swipe the Bernie Taupin-Elton John-Marilyn Monroe lyric.

Bill Dougherty, the man whose dogged labors put Vince and Batavia into the record book, died in 2017. I think of Bill, too, at this time of year, and I smile.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply