Athens

I am struggling up the slippery marble steps of the Acropolis with the Geldofs and the Bismarcks. We gaze upwards towards the façade of the Parthenon, whose simplicity has excited architects and conquerors for 2,000 years. There are no straight lines, everything curving upwards towards the center. The whole structure tilts slightly towards the west end, the side you first see as you arrive, hot and winded. Yet every column seems perfectly straight, an optical illusion as real as the glory that once was Athens.

The crowds are shabby and rather ugly — fat people speaking Spanish or Chinese, their children munching candy and ignoring the most beautiful structure ever built by man. The Parthenon’s subtleties are many: it arches, leans, swells and breathes. It also served as a place to make love in when I was a youngster. (It was open to the public but there were no tourists back then. Under the Athenian moonlight, mild breezes blowing, you had to be really gauche with women not to get lucky.)

Phidias, the man who oversaw the Acropolis project, was a friend of Pericles, and the gold plates, with which he covered the gown of the statue of the virgin goddess Athena, were worth about 25 million bucks in today’s moolah. (They were sold in no time to pay for mercenaries.) The tiny Winged Victory temple is as beautiful as they come, desecrated long ago by the hated Turks. The Venetian Morosini fired on the sacred site in 1687, as horrible an act as there is — and he was supposed to be civilized.

As Geldof expounds his theories and wonders how the Athenians, who prided themselves on their cultural superiority, passed down their wisdom, he suddenly changes tack and tells us about a popular quiz program for morons. When the panel is asked what Hitler’s first name was ‘Paddy hits the button first and blurts out “Heil”.’ All five of us collapse in laughter, but then it’s back to culture.

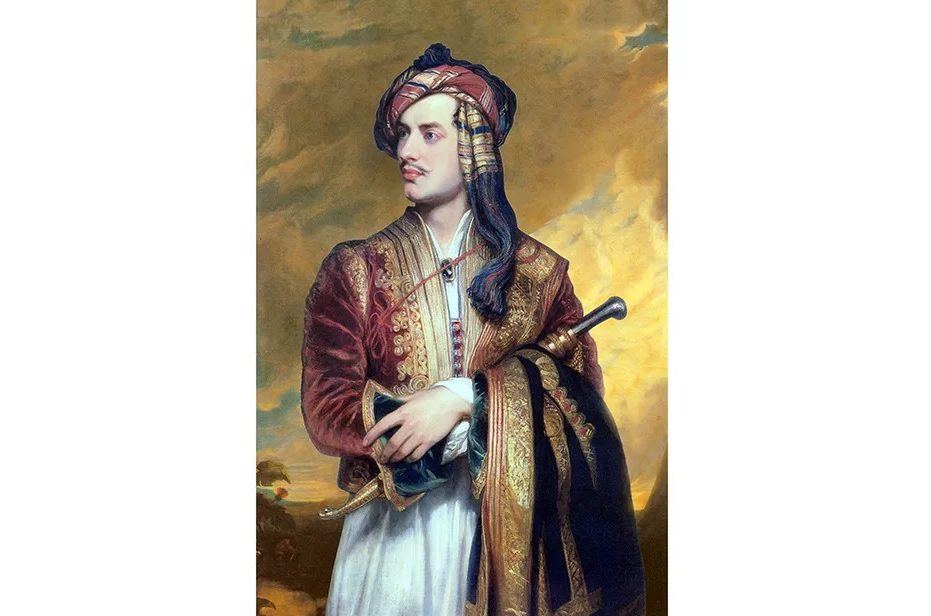

When Byron first came here in 1810, Athens had 10,000 denizens. The poet was at once buoyed in spirit but depressed by the ruins he saw. He launched a bitter attack against Elgin for his ‘vandalism’, calling him a plunderer and a grave robber. Byron would ride east to Sounion and admire the Temple of Poseidon and its Doric columns, taking about eight hours each way. It now takes an hour by car and four hours if you sail. ‘Place me on Sounion’s marbled steep,/ Where nothing, save the waves and I,/ May hear our mutual murmurs sweep.’ He was 22 and had 14 years to live, dying in Missolonghi in 1824 after his return to Greece. ‘For standing on a Persian’s grave,/ I cannot deem myself a slave.’

While lost in Byronic thoughts, I noticed three redheaded young women speaking with American accents and taking selfies as they posed in a stripper’s come-on manner. I approached them with Leopold Bismarck and introduced myself as a morality policeman safeguarding sacred grounds from foreign sacrilege. I’ve never seen three more terrorized beings. ‘This is simply a warning,’ I said. ‘The Acropolis is not a strip joint.’ They breathed easier and were about to thank me when I told them I was a simple tourist like them and was pulling their leg. They got angry and left rather abruptly. Bolle thought it quite funny. I wonder what Byron would have made of it?

Greece for me is territorial, but for many foreigners it is cultural and artistic. Hellenistic culture lasted until the final triumph of Christianity around 500 AD. It was both universal and centered on the individual. Every time I ascend that sacred rock, I go ape about my Greekness. It’s a strange thing. It is not necessary to become Roman to understand Julius Caesar. But to understand Aristotle is, in a small way, to become a Greek thinker. But how does a person achieve wisdom? That is a Socratic question. It has to do with the spirit. How does one become good? That was a Platonic question. Easy, says the ancient philosopher Taki. One cannot, at least according to Plato. Until Jesus Christ came along, that is. See what I mean when I say that Hellenism was over when Christianity came along.

As all Greek-speaking readers know, one shows respect by addressing someone in the second-person plural. The singular is used either when you speak to people you are extremely familiar with, or in order to show lack of esteem. When one of the housekeepers on the island asked me how the mother of my children was, in the plural, I replied that I had left my wife and was now looking for a younger one. The housekeeper looked appalled and said to me in the singular: ‘You’re an idiot.’ When I told Alexandra this, she said that Eleni, the housekeeper, was a very wise woman with good taste. (One can’t win against these females.)

On my last night in Athens, I sat up on a roof with the Geldofs and Bismarcks and reminisced about a great week that ended among the ruins of the Acropolis. I am now a ruin also.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.