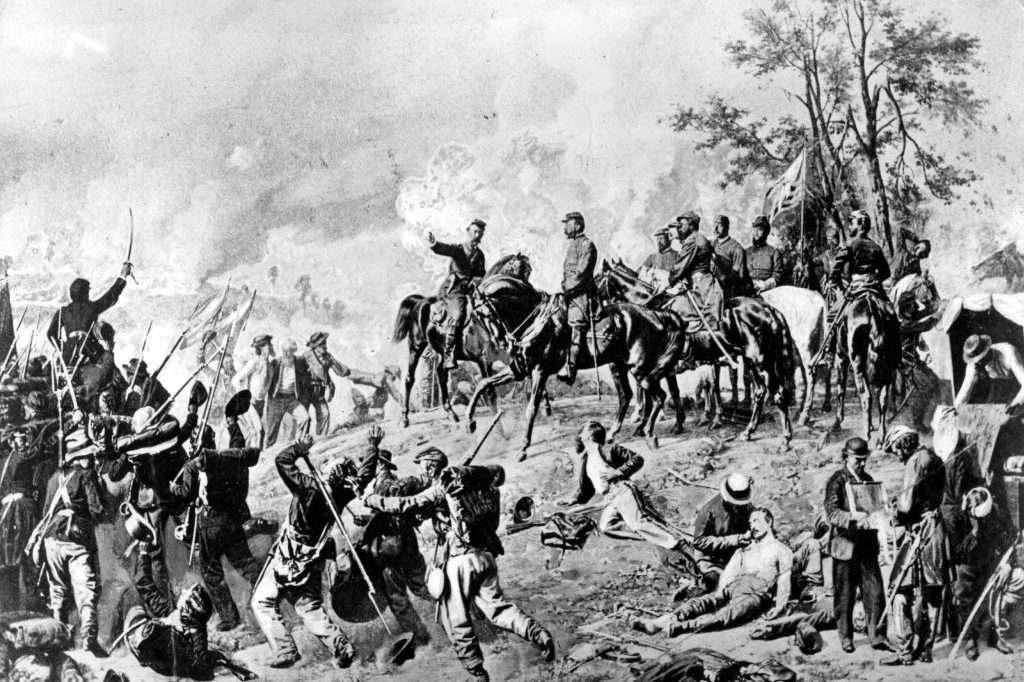

The Civil War, said Gore Vidal, is “the great single tragic event that continues to give resonance to our republic.” Gettysburg was its climacteric battle, and Ron Maxwell’s epic Gettysburg (1993), filmed on and around the battlefield, is the definitive cinematic treatment of the most consequential, written-about and argued-over military engagement in the history of the United States. (I would call it the most stirring as well but then I remember the words of the eminent historian J.G. Randall, best-known for his four-volume Lincoln the President: “That there was heroism in the war is not doubted, but to thousands the war was as romantic as prison rats and as gallant as typhoid or syphilis.”)

Based on Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels, a fixture in the very small canon of critically acclaimed Civil War novels, Gettysburg dramatizes the decisive three-day battle that left more than 7,000 dead and indelibly imprinted on the American historical memory Pickett’s Charge, the defense of Little Round Top by the 20th Maine and, four months later, President Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Over a mid-October weekend in Gettysburg, hundreds of peaceable movie-lovers and many cast members gathered to celebrate the tricennial of Gettysburg’s theatrical release.

Pulling into the opening night reception on Seminary Ridge, whence the Confederate survivors of Pickett’s Charge retreated on July 3, 1863, I saw well over 300 history-haunted Americans standing in a line that seemed to stretch all the way to Richmond, patiently waiting for pulled pork, local beer and autographs. They came from far and near, pilgrims for whom the American past is not dead nor doth it sleep.

Gettysburg, starring Martin Sheen, Jeff Daniels, Tom Berenger and a cast of — literally — thousands of reenactors, has attracted a following far too large for it to be termed a “cult” movie, though its fans are as rabid and given to multiple viewings as Rocky Horror Picture Show aficionados. (When dressing for the occasion, however, they lean toward gray frock coats and kepi hats rather than sequined blazers and fishnet stockings.)

The Ultima Thule of Gettysburg fandom is embodied in a Pittsburgh man who has amassed a stupendous collection of its props and costumes and who says that he has seen the movie (which in its briefest version runs 254 minutes) an astounding 3,000 times — a claim reminiscent of Wilt Chamberlain’s boast that he had conjugated with 20,000 women. One may admire the dedication of both men but…really?

The centerpiece of the weekend was the screening at the suitably named Majestic Theater on a Saturday afternoon of cold and drenching rain, perfect weather in which to view a four-and-a-half-hour director’s cut. The packed audience lustily cheered favorite scenes, whether Union Colonel Joshua Chamberlain’s “why we fight” oration, General Robert E. Lee’s inspection of the troops just before the disastrous Pickett’s Charge or the first glimpse of Confederate General James Longstreet’s movie beard, a boscage that might have provided nests for half the bluebirds in Adams County.

The subject of Gettysburg remains a touchstone, even an obsession, of those who understand that the United States did not begin last Tuesday. The battlefield attracts a million or so visitors a year, and Maxwell’s film is credited for not only adding to these numbers but, more importantly, enriching the experience. These are not National Lampoon’s European Vacation drive-bys; since the movie’s release, says Gary Adelman of the American Battlefield Trust, people have “wanted to get out [of their cars] and explore. Suddenly, the characters were real to them, and they wanted to see where they fought and died.”

Ron Maxwell’s Civil War trilogy, consisting also of Gods and Generals (2003) and Copperhead (2013), is sui generis in American cinema, and Maxwell’s fearlessness in pursuit of his vision and steadfast refusal to deform his films with presentism has earned him widespread and unusually passionate devotion — and sometimes disparagement — from the public and critics. (I wrote the screenplay for Copperhead, a home-front drama with nary a cannon blast or fixed bayonet.)

Robert Penn Warren, the Kentucky-bred novelist and American poet laureate, said that “experiencing to the full the imaginative appeal of the Civil War… may be, in fact, the very ritual of being American.” No filmmaker has explored the imaginative appeal of the Civil War in as much depth or from such diverse angles as Ron Maxwell. In a country whose dominant institutions are either contemptuous or neglectful of the American past, Ron Maxwell’s films constitute a profoundly moving statement of why it matters that our ailing republic shall not perish from the earth.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2023 World edition.

Leave a Reply