On June 8, 1924, veteran climber and geologist Noel Odell mounted the crest of a Himalayan crag and gazed up toward the tallest peak on Earth. Taking in the awe-inspiring sight, he noticed two tiny “objects” far ahead on a snowy slope “going strongly for the top.” To Odell, a trained and talented observer, the pair of ascending dots appeared to be a mere thousand feet or so below the summit. He later wrote that as he stood intently watching this dramatic appearance, the scene suddenly became enveloped in cloud and the “objects” vanished from his view. It was the last sighting of his fellow expeditionaries, George Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine, alive. As the final eyewitness account of their doomed adventure, Odell’s story is considered an essential citation when attempting to resolve the mystery of whether Mallory and Irvine ever made it to the peak. Given the lack of definitive proof, the climbing community remains divided over the possibility, and a century on, the outcome of their tragic ascent still looms large over the world’s highest mountain.

An hour after Odell’s observation, weather on the mountain took a turn for the worse. Concerned for Mallory and Irvine’s safety, he began the terrifying climb to find them. Through lacerating winds and blinding snow squalls, Odell searched in vain for eleven days, breaking a record for the longest time spent over 27,000 feet. When no signs of the pair were found, Odell used sleeping bags to signal back to base camp that the two were missing and presumed lost. The message he sent read: Abandon hope. Return to camp.

The 1924 expedition to Everest was Mallory’s third visit to the Himalayas. He had been an enthusiastic member of a reconnaissance mission in 1921 and played a key role in the record-setting first effort to climb the mountain in 1922, but the ultimate prize of scaling the pinnacle of the globe was precluded by bad weather and ill health. Given his age (he was thirty-seven), he knew the expedition of 1924 was his last chance to vanquish the colossus.

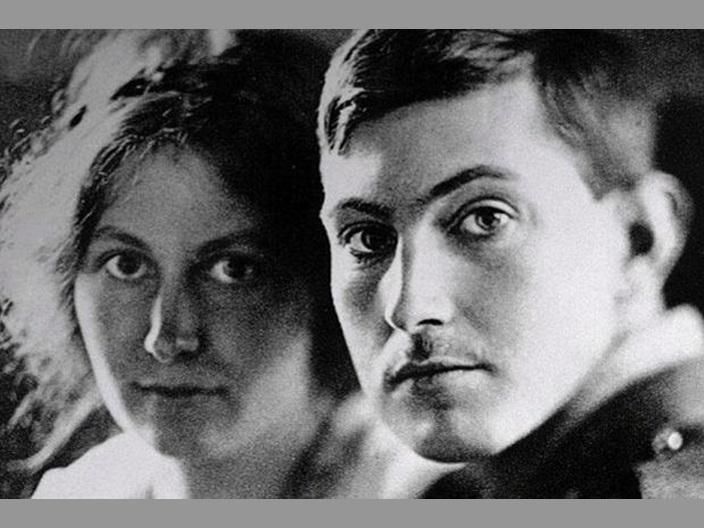

By the time of his death, Mallory was already something of a legend. His fertile mind impressed his tutors at Winchester and then Cambridge, where his shy demeanor and Grecian good looks endeared him to some of the most noteworthy figures of his generation. He socialized with Lytton Strachey, Rupert Brooke and John Maynard Keynes and climbed the Welsh peaks with the poet Robert Graves. After Mallory’s disappearance, Keynes recounted a conversation with his old Cambridge chum to a journalist, in which the mountaineer morbidly prophesied that his final expedition to Everest would “be more like war than adventure” and that he did not believe he would return.

Having witnessed the indiscriminate slaughter of thousands of young soldiers on the Somme, it is little wonder that Mallory wished to set himself a Herculean trial. Many survivors of the Great War nursed a death wish and felt a duty to the deceased to affirm life in the extreme. When Mallory heard of the first mission to Everest, he found the prospect too enticing to resist.

In April 1999, after years of planning, an Anglo-American team embarked on an expedition to discover the remains of Mallory and Irvine. It took them a surprisingly short time to find a mummified body lying face down, on a black slope of scree and ice. In a moment of intense drama, a member of the climbing party read aloud the name printed inside the collar of the corpse’s coat. “G Mallory!” he exclaimed, incredulously. There were no signs of Irvine. None of them had expected to find Mallory’s body so far down — it was discovered below the penultimate pyramid on the North Face, some 2,000 feet from the summit. They carefully examined the cadaver and managed to piece together the likely cause of Mallory’s death and the circumstances surrounding his fall. Mallory’s snow goggles were inside his jacket pocket, a snapped rope was tied tightly around his waist and the hands of his smashed wristwatch had fallen off. From these details, the team concluded that Mallory and Irvine were on the descent, so he pocketed his goggles. Sometime while traversing the Second Step — a notoriously tricky climb — Mallory tripped and the rope tethering him to Irvine broke. As he fell, Mallory sank his grip into the gravelly, snowy slope to slow his descent, splitting his fingers open and fracturing at least one of his legs. Irvine, presumably, was left alone at 28,000 feet. Being an inexperienced climber, he had little chance of survival.

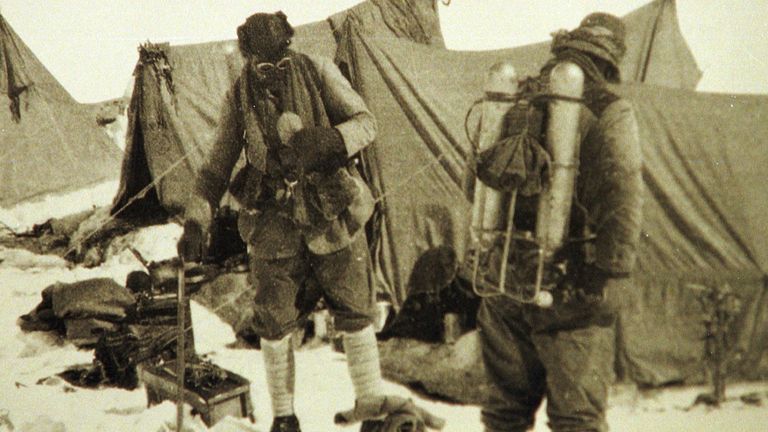

Irvine was a questionable companion for Mallory. The natural choice was Odell, but he was happy to climb in a supporting role, accepting the value of Irvine’s natural athleticism (Mallory’s rationale was that the combination of Irvine’s youthful vigor with his own climbing experience would be sufficient) and — more importantly — his technical expertise. Irvine had a background in engineering and knowledge of the rickety breathing apparatus the expedition had opted to use on this attempt. In 1924, no one knew if humans could breathe at such high altitudes and the 1922 climb had been aborted because of breathing issues. To alleviate the stress of breathlessness and mitigate the risk of asphyxiation over 28,000 feet, the expedition commissioned the manufacturing of oxygen canisters. Many of them broke on their way through Tibet and required constant tinkering if they were to be of any use. The exact whereabouts of Irvine’s body remain unknown, but it’s known that in 1975 a member of a Chinese expedition came upon what he called “an English dead” lying in a peaceful sleeping pose near the Second Step. Before the Chinese climber could be properly interviewed, he died in an avalanche.

Nevertheless, numerous clues are scattered across the frozen slopes of the North Face. In 1933, an ice-ax was found at 27,760 feet. As it was the brand of ax used on the expedition, and no other members of that venture made it as high, researchers have concluded that the ax must have belonged to Mallory or Irvine. In 1991, a 1924 oxygen tank was found 200 feet closer to the first step. Its discovery at 27,820 feet marks the minimum elevation Mallory and Irvine must have achieved.

There are several compelling reasons to believe the doomed duo did in fact reach the top, almost thirty years before Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. Mallory carried a photo of his wife, intending to leave it on the summit. It was not found on his person in 1999. Along with the pocketed goggles and notes that suggested the pair might have carried three, rather than two, canisters of oxygen, the missing photograph has inspired speculation that the climbers achieved their goal.

Mallory and Irvine were also carrying Vest Pocket Kodak cameras, specially designed to withstand falls and survive exposure in high altitudes. Experts from Kodak insist if those cameras are ever unearthed, there is still a serious chance their film can be developed. Imagine the image of an exhausted yet ecstatic Mallory surveying the vast vista of the Himalayas, perhaps with a weary but hearty Irvine beaming in the background. Such a snap would change the history of Everest.

Mallory was an eloquent man, blessed with both a precise and a poetic turn of phrase. Had he lived, he might have continued his academic life or turned to writing full-time, but his powers of eloquence were far from wasted.

Whether or not they know the source, the whole world knows his response to a question from a New York journalist. Asked why he wished to climb Everest, Mallory coolly replied: “Because it’s there.” But his most profound reflection on the compulsion to climb monstrous heights against perilous odds was jotted down in a diary. “Why do we travel to remote locations? To prove our adventurous spirit or to tell stories about incredible things? We do it to be alone amongst friends and to be in a land without men.” That nicely sums up the ethos of exploration and the heroic attitude of his adventurous generation.

Mallory and Irvine may have made it to the top, but whether they did is ultimately unimportant. Through their sheer zeal and audacity they transformed the most imposing mountain in the world into a monument to human fortitude. We may never know if that daring pair pushed ever onward and upward until there was no ground left to tread. What we do know is that when Odell lost sight of their ascent, he saw them leave the living world behind and step into mythology.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply