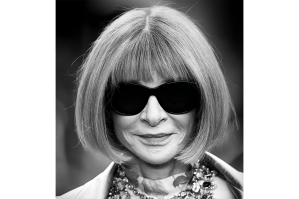

Dame Anna Wintour, with her rather marvelous bob hairdo, recently became chief content officer for Condé Nast. I had forgotten that a couple of years ago she was appointed a Companion of Honour – one of those interesting people King Charles III likes to have for lunch. And I couldn’t remember whether I’d written here about content. “That is probably not a sign of dementia,” said my husband encouragingly.

Why is content such an unpleasant label for articles in a magazine? After all, the title page of the Great Bible, ordered to be published by Henry VIII in 1539, read: “The Byble in Englyshe, that is to saye the content of all the holy Scrypture, bothe of the olde and newe testament.” Still, no one ever thought of Moses as a content-provider.

I suppose the trouble is the parallel with the contents of a barrel of sprats or the contents of my lifesaving handbag. Even so, 19th-century critics liked to distinguish between form and content. The great leap forward came with the invention of the World Wide Web in 1989. In 1991, a journalist wrote: “Microsoft is purchasing content – books, artwork and video properties – that can be used in products once multimedia computing is established.” The internet was the medium; it only needed the message.

Newspapers had always required editorial matter to put between adverts (although in magazines such as Exchange & Mart or the Lady they were the attraction). This matter was called copy. “More Copie, More Copie; we lose a great deale of time for want of Text,” wrote playwright and poet Thomas Nashe. In the 20th century, copywriters were devoted to advertising, an even more vulgar trade than journalism. Each generation has a fashion in language as much as in its bobs and fringes. The BBC favored the Orwellian-sounding controller. I think there was a Controller of the Spoken Word. Now we get content officers.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply