Portage, Michigan

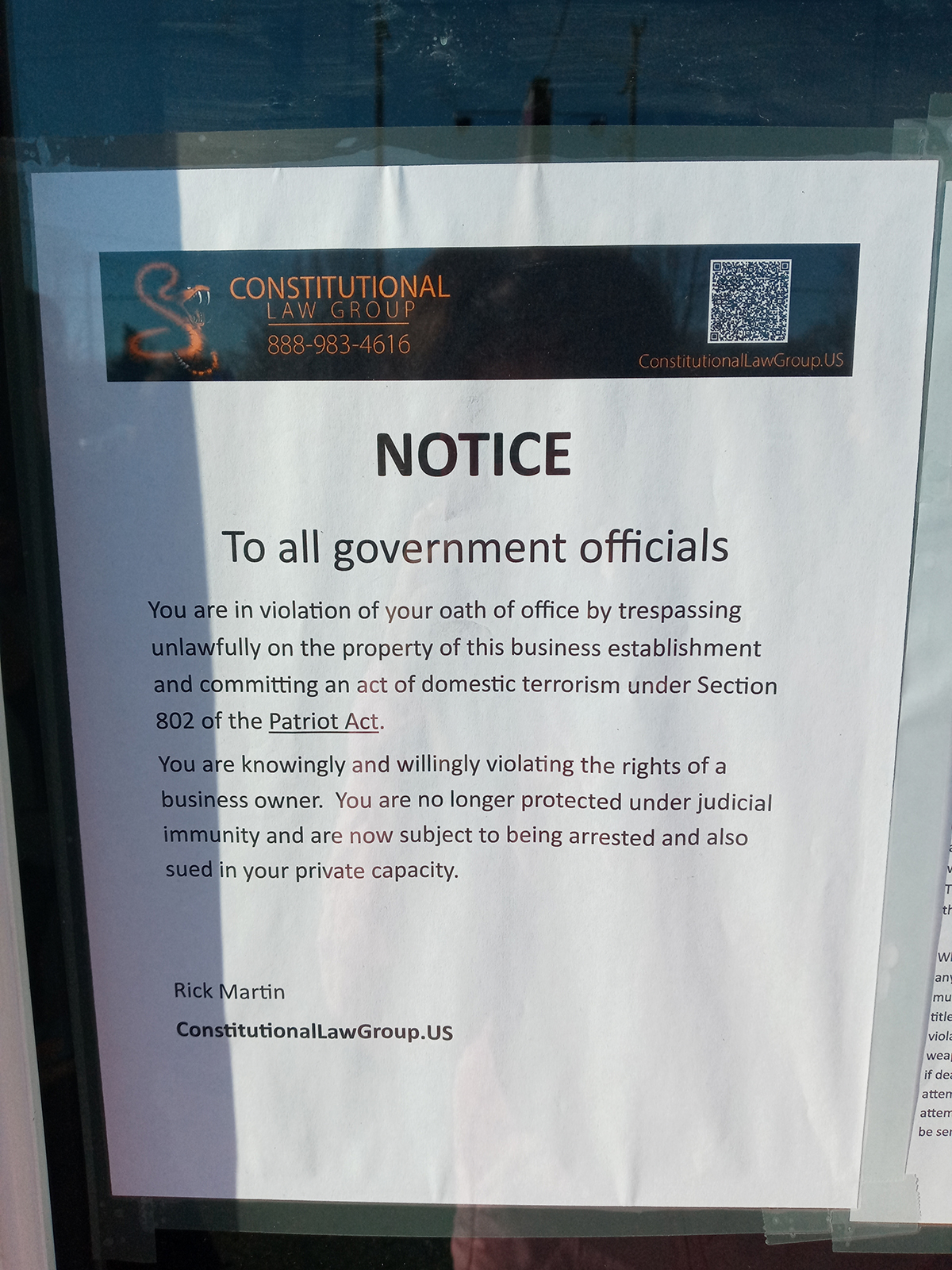

The short notice taped to the door is addressed ‘to all government officials’. It gives them a warning: ‘You are in violation of your oath of office by trespassing unlawfully on the property of this business establishment and committing an act of terrorism under Section 802 of the Patriot Act.’ Taped up next to it, a longer warning in black and set-off red type, with Title 18 from the United States Code copied out underneath. I pull out my phone for a snapshot, then walk back to wait in line.

On this particular crisp December morning, a small group has gathered outside the D&R Daily Grind Café in Portage, Michigan. This tiny building has been the small town’s only open restaurant since owner Dave Morris chose to resume business on November 27, defying Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s November 18 epidemic order. Initially set to expire after three weeks, the order was extended to December 20 within a week of my visit. Whitmer has gone on record saying ‘If everyone could stay in place for three weeks, this virus would be gone.’

So far, Morris’s choice not to wait has paid off. My car is parked under a ‘No Parking’ sign, the only spot I could find as I nosed around the lot. The first woman I speak to tells me she heard about the restaurant from her nephew in Saginaw, after it was spotlighted on Channel 3. After watching the story, she thought ‘Well, I know where I’mma eat breakfast tomorrow!’ I look around and note that none of us are wearing masks. She tells me she nearly passed out in the grocery store from an asthma attack when she tried one. When strangers demand to know why she isn’t wearing one, she tells them ‘You don’t get to ask me that.’

The smell of fried things wafts out to us as we wait. A tall man behind me is chatting up the little line, beaming through a full beard and dark glasses. He wears a knit cap and a jacket vest over flannel. His right arm rests in a sling. I ask if he’d mind being quoted for a story. ‘Sure! What do you want to know?’ The woman with him grins and says ‘Oh, he has plenty to say!’

His name is Gary, and he’s driven 40 minutes west from his hometown. His sling is from rotator cuff surgery. He has been to three different hospitals. ‘Not one of them is full,’ he tells me. He’s been running a barbershop for three years. Before that, he was a sometime truck driver and cemetery worker. Before that, a soldier with two tours in Iraq. He is currently allowed to stay open, but only under certain restrictions, which he is ignoring. ‘I practice civil disobedience every day,’ he says, grinning. When I ask if he masks up, he says he’d gladly do it for any customer who specially requests it, ‘But guess what? Not one person has asked me, and none of them want to wear one either.’

Gary wasn’t always against strictures. ‘I was all for it back when we didn’t know what [the virus] was. Now, I’ll never stop working again.’ Now, being called a criminal has the opposite of the intended effect on him. ‘The more you keep calling me a criminal, the more you make me want to be one. I don’t mind going to jail. But,’ he adds, ‘I know I won’t.’ Up north, friends of his who are sheriff’s deputies are simply not enforcing the order. ‘They don’t care.’

We’re soon joined outside by Morris himself, masked but smiling at everyone with his eyes. Morris was caught in a heated moment on live television but is relaxed and friendly this morning, expressing heartfelt gratitude to the customers. ‘You never know which way this is gonna go when you do it,’ he says, but he’s glad to know there are so many ‘American patriots’ willing to show up and show support. He has said that he and his wife would shut the place down if a case was reported, but in the past nine months they haven’t had one.

All tables inside are still full. Gary repeats to several of us his frustration that small businesses are getting restricted while Walmart and Meijer remain open. Another man in line with a landscaping company agrees. He runs a small ‘one of everything’ outfit, but recent months have wiped out half the business.

Cars occasionally honk as they drive past, one driver flipping us off according to a woman who caught it. A baby girl toddles around our feet meanwhile, observed watchfully by her mother, aunt and grandmother. She prefers her hood down. Her aunt is concerned to replace it. ‘Oh, let her do what she wants!’ Grandma says. A bit later, I see Grandma scoop her up before she makes it to the street, to her loud but temporary dismay.

Finally, a father with small children walks out. I take their table and take coffee, which the harried young waitress will refill several times. The TV over the counter is quiet, running Crikey! It’s the Irwins. On the shelf next to it, a little sign reads ‘Good morning. Let the daily grind begin.’ Framed Readers’ Choice certificates cover the wall to my left, dated 2009-2011 — Best Breakfast, Best Hamburger. The wall to my right is flanked by blinded windows with Christmas wreaths on top. A plastic-wrapped conditioning unit has been installed where a window used to be. Two photographs dominate, one a print of the iconic ‘Lunch Atop a Skyscraper’ shot, the other one I can’t place in memory, of waiters serving lunch in a similarly precarious position.

I order the ‘potato mess’, which comes after a long wait and consists of American fries, sausage and onions smothered in gravy. It’s enough and more. The baby and her entourage settle down in one corner, Gary and his lady in the other. A younger woman in paisley pants, slippers and a poncho leans on the counter. She’s been gathering signatures for a ‘Recall Whitmer’ petition. They have 500 so far, something-million to go.

Morris himself is circling tables with the waitresses. I hear that the cook is going crazy in the back. At one point, a biker in a Trump mask briefly pops in, sees the full house and leaves a generous tip.

[special_offer]

Eventually I finish, box up my leftover mess and go to pay. There’s some trouble with the credit card machine, but it finally goes through. I ask the woman working it if the place has incurred any of the threatened fines ($1,000 per day). She says they haven’t had a citation yet.

I wave to Morris as I leave, and he grins back, now maskless and giving me a chipped-tooth smile. I shake hands with Gary, who looks youthful without his glasses and cap. As I leave, I think about the thing he said that stuck most with me: ‘Every day I wake up, I’m dying.’ He could get sick. He could get hit by a car tomorrow. Anything could happen.

But Gary doesn’t let that worry him. Gary can’t afford to.