When we were little we used to go on holiday to the same place in Brittany, a picturesque, quiet coastal town. There wasn’t a lot to do there for children, but I always looked forward to the holidays because of the food. It was the first time I was exposed to French food, and it was a revelation.

I was an adventurous eater, taking after my father. Anything he ordered, I would try. Even as a little girl, I remember a sense of pride in my fearless eating: huge pots of mussels, big shell-on prawns, strong cheeses — I was game for anything. But there was one exception.

Brittany has its own crèpe, the savory galette, and I could not get on with it. It looked great: fried egg, chunks of ham and lots of melted cheese — but the galette itself tasted so weird. I tried again and again, but it wasn’t for me. Other sweet, standard crèpes were fine, but they were for children! They had Nutella on them, for God’s sake! I wanted to be precociously intrepid in my eating, but I was being felled by a pancake.

Thankfully, as tends to be the case with acquired tastes, it was a taste I eventually acquired. Who’d have thought? And now there are few lunches I love more.

Breton galettes are made with buckwheat flour rather than normal wheat flour. Buckwheat flour has an unmistakable flavor: earthy and nutty, extremely savory, and a little bitter. It’s not actually a grain but a “pseudo-grain” — which means that it’s gluten-free. In baking, you would usually use it alongside another flour, but there’s no need in pancake batter, which doesn’t need gluten development. It means that the finished galette, unlike paler, softer crèpes which are made with normal wheat flour, is dark gold, crisp and lacy.

According to legend, the first Breton galette was an accident, made when a farmer spilled buckwheat porridge on a hot surface. I’m not convinced: to make a buckwheat galette, you need a very thin batter that bears little resemblance to porridge. It seems more likely that someone simply made pancakes with the nutty local flour and liked the result — but then I’m a cynical old bird when it comes to culinary origin stories. They all seem to involve an implausibly clumsy cook.

In Brittany, galettes are everywhere, sold at small street stalls, or in more formalized crèperies with seating, or in restaurants more generally. As is the way with street food, they’re fast to make, cheap to produce and best eaten straight away, hot and salty, and preferably oozing with cheese or butter. I remember being mesmerized by their production: old men deftly wielding small wooden tools that looked like they could be used to tend a zen garden. The batter is swept across a big, flat, round hotplate, then the edges are coaxed away from the surface, before being folded neatly while still hot into perfect squares and triangles to contain the fillings.

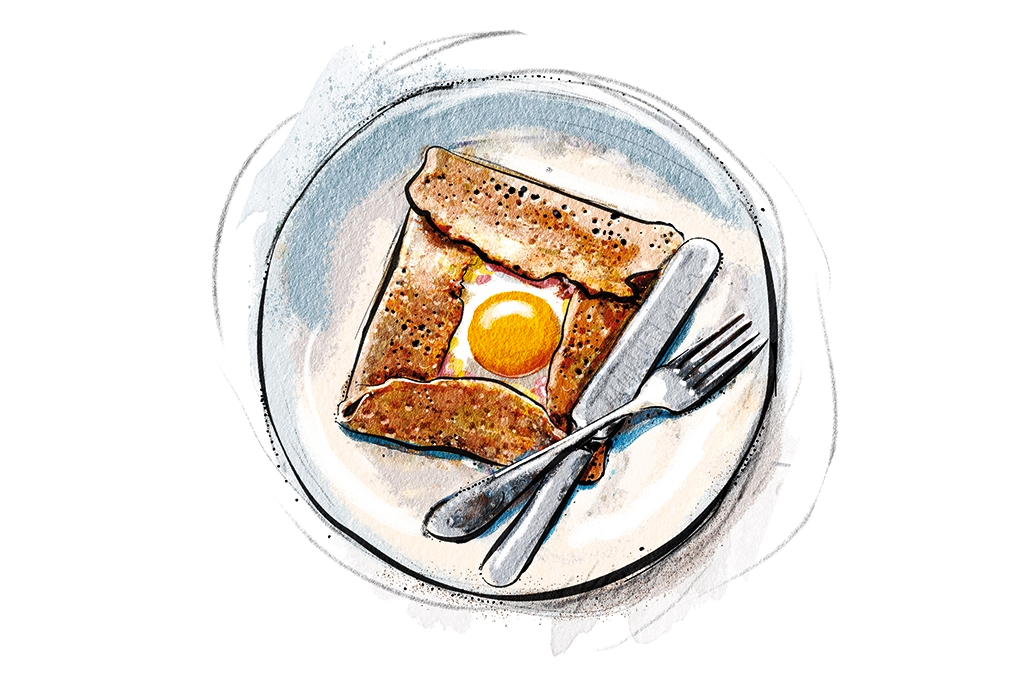

Assuming you don’t have a crèpe maker and paddle, a big non-stick frying pan and a spatula will do the job just as well. The batter is incredibly simple — a mixture of buckwheat flour, milk, egg and a little salt — but needs to be left in the fridge for at least a couple of hours, or overnight, to let the flour hydrate. Once it has rested, melted butter is added, and the batter is then cooked on one side in a hot pan, with the fillings being added on the uncooked side. As with most fast foods, you can fill the galette with whatever your heart desires (or your fridge contains): it’s pretty great just with butter (salty, as is right and proper for a Breton speciality). But the classic is a “galette complête,” also known as the “galette Bretonne,” with ham, cheese, and an egg cooked into the centre of the pancake, the four sides flipped into the middle, showing off the perfect yolk.

Serves 4 Takes 10 minutes (plus at least two hours in fridge) Cooks 5 minutes

For the batter

- 3½ oz buckwheat flour

- 10 fl oz milk

- 1 egg

- 1¾ oz butter

- A pinch of salt

For the filling

- 4 slices of ham, torn

- 3½ oz gruyère, grated

- 4 eggs

- To make the galette batter, mix the flour, salt and egg with half of the milk in a bowl or jug, stirring to a smooth paste. Add the second half of the milk and stir to a thick batter the consistency of single cream. Refrigerate for at least a couple of hours, or overnight

- When you’re ready to cook the galettes, melt the butter in a non-stick frying pan and pour it into the batter, stirring thoroughly

- Pour a ladleful of the batter into the hot pan, swirling so that it reaches the edges

- Crack an egg into the middle of the batter, and spread the white around a little bit with a spatula

- Scatter the ham and gruyère around the egg white, and then gently lift each of the four sides of the galette up, folding them towards the center, but keeping the egg yolk exposed. You may need to hold the sides in place for a moment until they stick. Continue cooking until the egg white is opaque, then carefully slide from the pan on to a plate

- Repeat with the rest of the batter, eggs, ham and cheese

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.