The issue appeared without fanfare at the 2017 US Open giftshop: a bright-red background offset an Impressionist yet unmistakable painting of Yannick Noah hitting a forehand, dreadlocks flaring. And with that, publisher Caitlin Thompson and editor-in-chief Dave Shaftel — an unlikely journalism pair who had met bonding over the poor state of tennis media — announced the launch of Racquet magazine, a journal that would explore the lifestyle, culture, history and zeitgeist behind modern tennis. In his first editor’s letter, Shaftel more or less laid out his and Thompson’s grand plans. “We don’t think of the game as a country club sport lumped in with golf and healthy only in the suburbs,” Shaftel wrote. “We fondly remember the swashbuckling sport of the tennis boom of the 1970s and 80s, and our goal is to help restore some of that swagger to today’s game.”

Issue number one of Racquet landed with both provocation and pizazz. Shaftel, a onetime freelance writer for the New York Times, brought the writing chops — Giri Nathan, A.J. Eccles, Gerald Marzorati and Joel Drucker, among others — and kicked off with stories on the unconventional life of its coverboy, Noah; the fashion designer and gay player, Ted Tinling; the rescue of Forest Hills Stadium by music enthusiasts and the Queens community; as well as a bold essay taking a shot at how “fans deserve a real world cup for tennis,” not the Davis Cup.

Subsequent issues explored the performance-enhancing drugs for which Maria Sharapova received a two-year ban, former Russian president Boris Yeltsin’s love of tennis (and vodka), the overlooked talent of coach Michael Joyce, as well as the reclaiming of the Fred Perry shirt from white supremacists. Roger Federer didn’t even make an appearance until issue four, and only really on the cover, in which he holds a trophy in a ticker-tape parade.

Thompson brought in the money and the brands, with ads for offbeat clothing, like Rowing Blazers, photo essays that pushed the envelope — tennis socks and homemade handballs — as well as a twelve-page portfolio of the Catalonian cubist artist Març Rabal. She took even more risks with a few small events, some merchandise and a podcast, which she started on her own, then added World Grand Slam doubles champion, Rennae Stubbs, an ESPN commentator.

And for about five years, the Racquet machine chugged forward. It received lots of kudos — “Deliciously smart… a game-set-match of literary bona fides,” wrote the New York Times’s T magazine — and head-buzzy cover designs, not necessarily journalism awards, but certainly recognition. (Neither Shaftel nor Thompson responded to repeated requests for interviews.)

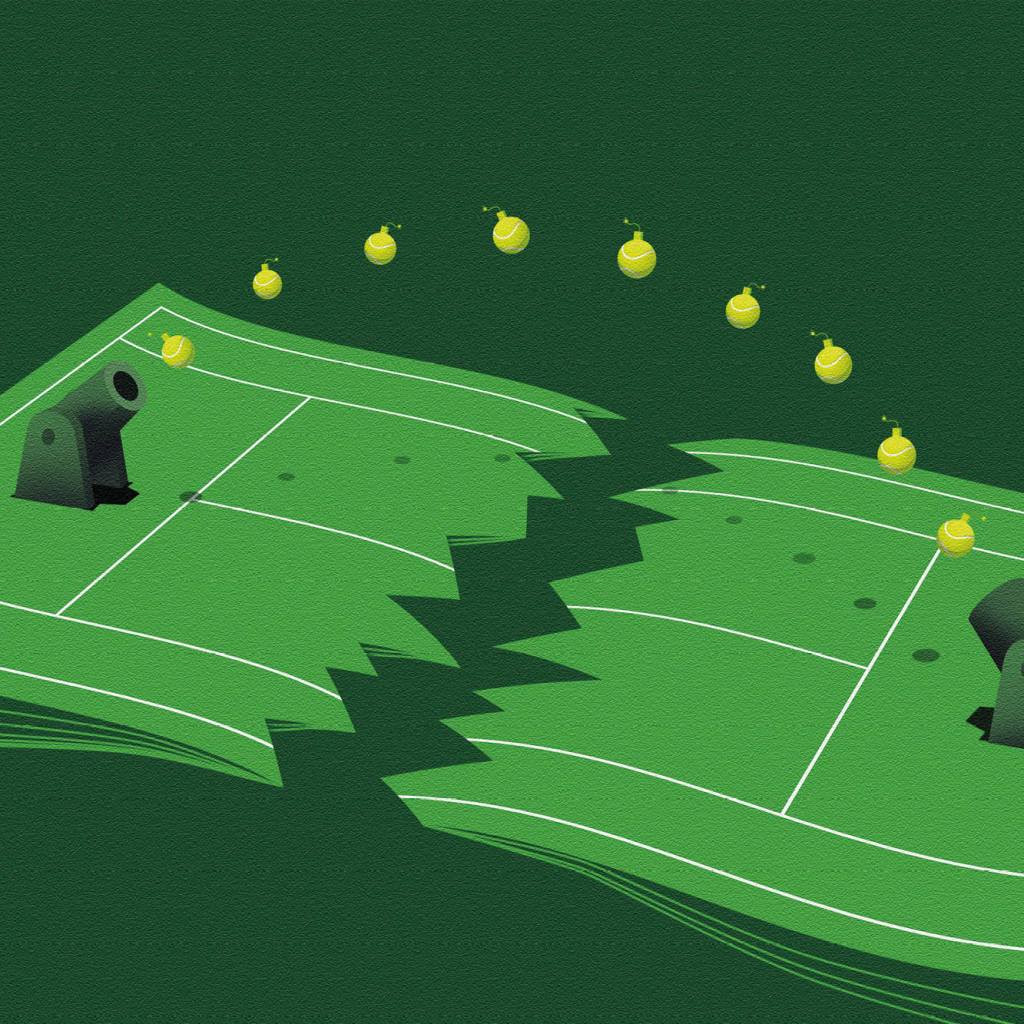

But as they often do, ideas clash, camps are divided, and Racquet eventually became a cautionary tale about both the magazine business and the constant ambition to build the greatest brand, rub elbows with tennis elite — on- and off-court — and dominate the business. Seven years into their venture, Shaftel and Thompson have separate magazines, and the pair are now locked in opposing lawsuits alleging, on Shaftel’s part, that Thompson was an “unmitigated disaster,” as a business manager and on Thompson’s that Shaftel stole “confidential and proprietary information” to start his magazine, Open, which “mimics” Racquet. It was a friendship-shattering fall from the top of the tennis world and a very public examination of the fragility of the independent magazine business, which keeps growing every year despite every niche seemingly filled.

“We had a schism in the way we wanted to go forward with the business,” Thompson told Defector in November 2023, when Racquet announced it would stop publishing. “Increasingly we’ve been growing, which is great, but also we’ve had a difference of opinion in how to spend our time and how to punch above our weight, as something really small.”

Shaftel has another point of view: “She will say that the company was insolvent, and I wouldn’t let her raise money, because she needs me to sign off to raise money,” he told Defector, a website started by one of Racquet’s main contributors, Giri Nathan. “That is true, but if I was to take a red pen to that statement, I would say: we are insolvent because of her reckless actions, and I wouldn’t let her raise money because I lost faith in her leadership.”

While Shaftel wanted to spend on journalism — and did, mightily, on Ben Rothenberg (more on that later) — Thompson was a devotee of the Tyler Brûlé mode of journalism, the Wallpaper and Monocle model, in which a magazine becomes the creative agency for the brands it spotlights. Racquet’s goal was “identifying a niche audience centered around highbrow tennis culture and providing a premium experience at a premium price,” Thompson told the 2017 Nieman Journalism Lab. Thus the creation of the Racquet House: starting with the 2020 BNP Paribas Open in Indian Wells, Racquet would rent a local house in Palm Springs, invite brands to pay for exposure and goods, and those brands would receive not only a good party, but also beautiful tennis people snapping beautiful photos, and in some cases brand reps would get to play a tennis game.

Racquet had a good run at Palm Springs and at the Racquet House at the Palais de Tokyo, so during the 2023 US Open, Thompson dreamt bigger. Rather than just renting a house in Flushing, Queens, she wanted Rockefeller Center. Racquet put a tennis court on Center Plaza in the heart of the city with player stop-ins, talks, autograph signings and even a little tennis. Thompson, who aimed one day to open branded tennis clubs all over the world with Soho House-style membership plans, ran a popular event. Unknown to Shaftel, however, after sponsors pulled out, Racquet owed $250,000 in fees for Paris and another $250,000 for Rockefeller, leaving the pair $500,000 in debt. “We were out of money before [Racquet House NYC],” Shaftel told Defector. “The fact that that happened again, and we lost a ton of money again in New York, three months later… I just couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe we were in the same position again, and once that happened, things were irrevocably fucked.” Calling Thompson’s vision “too grandiose and unrealistic” and explaining he had “lost faith in her leadership,” Shaftel split — along with his cadre of well-known writers. Thompson was ultimately granted the rights to the magazine, the podcast and the website — and all the debt.

But with her “spiritual advisor” — long-time Esquire editor David Granger — on the masthead, Thompson relaunched Racquet at a co-hosted Wimbledon party with cloud server ASP in June. Five days later, Shaftel announced his own new venture, the Second Serve — currently a website with a print edition, Open, coming to shelves — with a raucous DJ-slamming, Live Tennis party at the otherwise prim and proper Cumberland Club in North London.

But before it all blew up, Racquet and Covid, among other things, ushered in an era of unprecedented exposure for tennis — Netflix’s Break Point be damned. Racquet showed the world Naomi Osaka six months before the nascent star won the 2018 US Open. The magazine put out a book of its best writing, covered tennis in Haiti and Nigeria, and introduced Gagosian-worthy artists, such as Honor Titus, into its circle of moneyed supporters. Racquet also inspired and challenged several other magazines to try to emulate its success overseas: Courts in France (which looked, felt, smelled and tasted more or less like Racquet) and Bagel magazine in the UK, a more rock ’n’ roll tennis magazine, as well as Substacks and other spin-offs that drafted behind them: Finite Jest by Racquet contributor Andrea Petkovic; Christopher Clarey’s Tennis & Beyond; A Thread of Order, The Tennis Podcast; and even Served with Andy Roddick.

“I had grown up reading tennis magazines Serve + Volley and Ace, and I think many of us are nostalgic for the feeling that Racquet and some of the others give us,” said Stuart Brumfitt, the founder of Bagel, a tennis publication on the hunt for its own unique stories, such as one about the Filipino tennis community in Los Angeles. “We do different patches — it’s easier for us to cover the European swing, for example. And to be honest, we’re really young — we still have to figure out the costs and the business side. It really started as a fun hobby, but my partners and I have worked at some of the best magazines in the world, and Racquet was lovely to see, although it wasn’t the inspiration.”

But in the fall of 2020, one of Racquet’s rising star writers, Ben Rothenberg, who hit some forehand line-drives and some base-line bombers — a story on Monique Viele supposedly connecting the Rick Macci tennis protégée and sex symbol with Donald Trump — went for a big story, following up off an Instagram post. With that, Rothenberg became Shaftel’s costliest business mistake.

The young journalist, who has always seen himself a bit of a “muckraker” in an upmarket sport, saw an Instagram post from a woman named Olya Sharypova saying that she, a former tennis player who grew up with Alexander Zverev, had been abused by an ex-boyfriend. The Russian media descended and confirmed that the ex-boyfriend was indeed German star Zverev. Rothenberg had formerly been friendly with the player and his family, penning a favorable 2017 story called “Family Band” about the emigration of Zverev’s parents, Alexander and Irina — well-regarded players in their own right — from Russia to Germany in order to give “Sascha” the best possible future. “To hear Alexander Zverev Sr. tell it, the tale of how his younger, golden-haired son began to play tennis has the simplicity of a fairy tale involving the Three Bears. ‘It was all natural for Sascha,’ he said. ‘Mama played, Papa played, brother played. And so, he started to play,’” Rothenberg wrote in the story. The article went on to describe how the family traveled with the beloved family dog, Lövik, a “toy poodle who does not play tennis himself but seems to enjoy the sport.”

But once Rothenberg got word of Zverev allegedly beating up on his girlfriends while holed up at a New York hotel during the 2019 US Open, he went straight for Zverev’s jugular. Relying on screenshots provided by Sharypova, Instagram posts and interviews with a childhood friend, as well as his Russian sponsor in New Jersey, Rothenberg put together a she said/ Zverev’s spokesman-said account of nearly two years of entrapment, emotional abuse, verbal abuse and physical abuse. Sharypova, according to Rothenberg, had not gone to the authorities with her story because “she didn’t want anything from (Zverev)” and the Lotte New York Palace hotel, where Sharypova allegedly ran barefoot into the lobby before seeking help from strangers on a New York City sidewalk, “would only release (video footage) if subpoenaed to do so, and did not guarantee that it had been preserved,” after Rothenberg inquired. As shaky as the story was, Racquet published it anyway, in November 2020. Zverev and his lawyers immediately sued. (Months later, feminism didn’t seem to be on Racquet’s mind when it backed a “zine” about New York tennis that ran a photo feature highlighting several “up the skirt” and wet t-shirt photographs of a sweaty female player.)

Whatever strain Shaftel and Thompson felt about each other’s business practices buckled under the Zverev lawsuit and the story’s publication. That could have deterred all three parties, especially Rothenberg, but they doubled down with a follow-up appear- ing in Slate magazine months later. Rothenberg claimed that “strong American laws around freedom of the press would have given Zverev’s claims” — likely of defamation, slander and libel — “no chance of succeeding,” so instead the player filed in Berlin courts, which, according to Rothenberg “have a reputation for being favorable to celebrities in cases against the media.” Nonetheless, Racquet initially footed Rothenberg’s legal bills, but as the business fell apart, Shaftel and Thompson left him with a $24,000 tab. “In May, the remaining publisher abruptly halted her support for the case, stunning both myself and our lawyer in Berlin, who said he has never seen a publication treat a journalist in such a manner in his decades in working for press law,” he claimed in a GoFundMe. After Rothenberg had a story about his plight run in the Washington Post, he raised $37,000, much of it given to him by Kevin Anderson, the South African tennis player who lost to Zverev six times.

After Zverev was cleared by the ATP of any wrongdoing and the cases made their way through courts, Racquet limped along with its quarterly print publication and the occasional unscheduled Rennae Stubbs podcast whenever the commentator and newly minted coach could make time to sit down in front of Thompson’s microphone. Each print run ran about 5,000 issues and mostly sold out, although by then Courts, the French magazine that used the Racquet playbook, Bagel, Tennishead and several online magazines, the Tennis Gazette among others, had stepped in to break news and stepped up tennis’s presentation to the world.

In his GoFundMe, which managed to keep Rothenberg out of debtor’s prison, the cavalier reporter spared Shaftel, but hit back at Thompson. “When I spoke to (Thompson), she said she still stood by the reporting in our story, but was upset that I had taken a freelance assignment for (the Second Serve) started by her Racquet co-founder.” Oh, and the Rothenberg story also cost Racquet its Adidas patronage — Adidas is Zverev’s sponsor — for a party in 2023, Thompson claimed, thus another reason to keep Rothenberg out of her pages.

Where does this leave Racquet, Rothenberg and the rest now? In debt with a wide-open coverage space to fill, few resources to do it and no real formula on how to acquire those resources. Also, it leaves at least two parties in court… not the pleasurable one outdoors, as the Rothenberg situation continues.

After a six-year stint, Courts — a Belgian coffee-table magazine that catered to the European/French-speaking market — largely ran out of money and moxie in early 2024. Laurent Van Reepinghen, a tennis-loving attorney with more than a passing adulation of Racquet, made a last-ditch effort with a money-raising campaign looking for about €30,000 to pay off some outstanding debt. However, Courts (to which this writer has contributed) underestimated both the amount it owed and the cost of a gallery show it produced, as well as some of its giveaways. With an exhausted Van Reepinghen at the helm (he did duties as both editor-in-chief and publisher and still continued to practice law), sizable debt and growing despondency over the business — Racquet openly disparaged Courts — Courts quit publishing around June 2024.

Bagel magazine is off to a good start with two issues and several events, including one featuring Lacoste and Grigor Dmitrov immediately before the 2024 Wimbledon. “We stick to tennis because that’s what we know and that’s what we love. I think the challenge is to keep finding original stories outside of the day-to-day coverage,” Brumfitt said. “Andy Roddick has loads more to say than I do. We don’t need extra podcasts or analysis.”

Bagel and Courts and Racquet have all at some point taken commissions from clothing companies such as Sergio Tacchini, FILA and Gucci to shoot cover spreads. That model won’t change anytime soon. Another publication, Tennishead, has built a tier-based sponsorship system that gives out ASICS shoes and apparel, as well as CLIF bars and coaching, to members. The latest tennis newsletter to materialize has been Bounces. It’s by Ben Rothenberg. He almost gave up covering the sport, he told the Washington Post, but “one of the things I heard often from those who urged me to keep writing about tennis was about how few voices like mine are in the sport. That’s a qualitative judgment — and it could be backhanded compliment from some, who knows —but the quantitative diminishment of tennis media is undeniable…” he wrote in his first edition.

For now, the journals battle on, the one with the biggest swing often winning. As the lawsuits between Shaftel and Thompson move forward, media pundits can look to that one to heat up, while Bagel and Courts and some of the others stand on the sidelines. “I’m a little bit of an anti-authoritarian. I don’t really believe that the people in charge necessarily know what they’re doing — and that includes me, by the way,” Thompson told New York magazine, just before the Racquet break-up. “I just feel like everyone’s kinda making shit up. So let’s just try to measure ourselves based on the amount of good work we do instead of performing the idea of work without actually doing stuff.

“Now, I get to just be myself at all times. I also hope that it comes with a relentless positivity and the idea that the door is always open and I’m always happy to collaborate. I couldn’t really dream of separating myself because this feels like what I’m supposed to do. We’re giving a voice to people who the sport has needed this whole time and we’re paying people to participate in it. It’s a tremendous accomplishment.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply