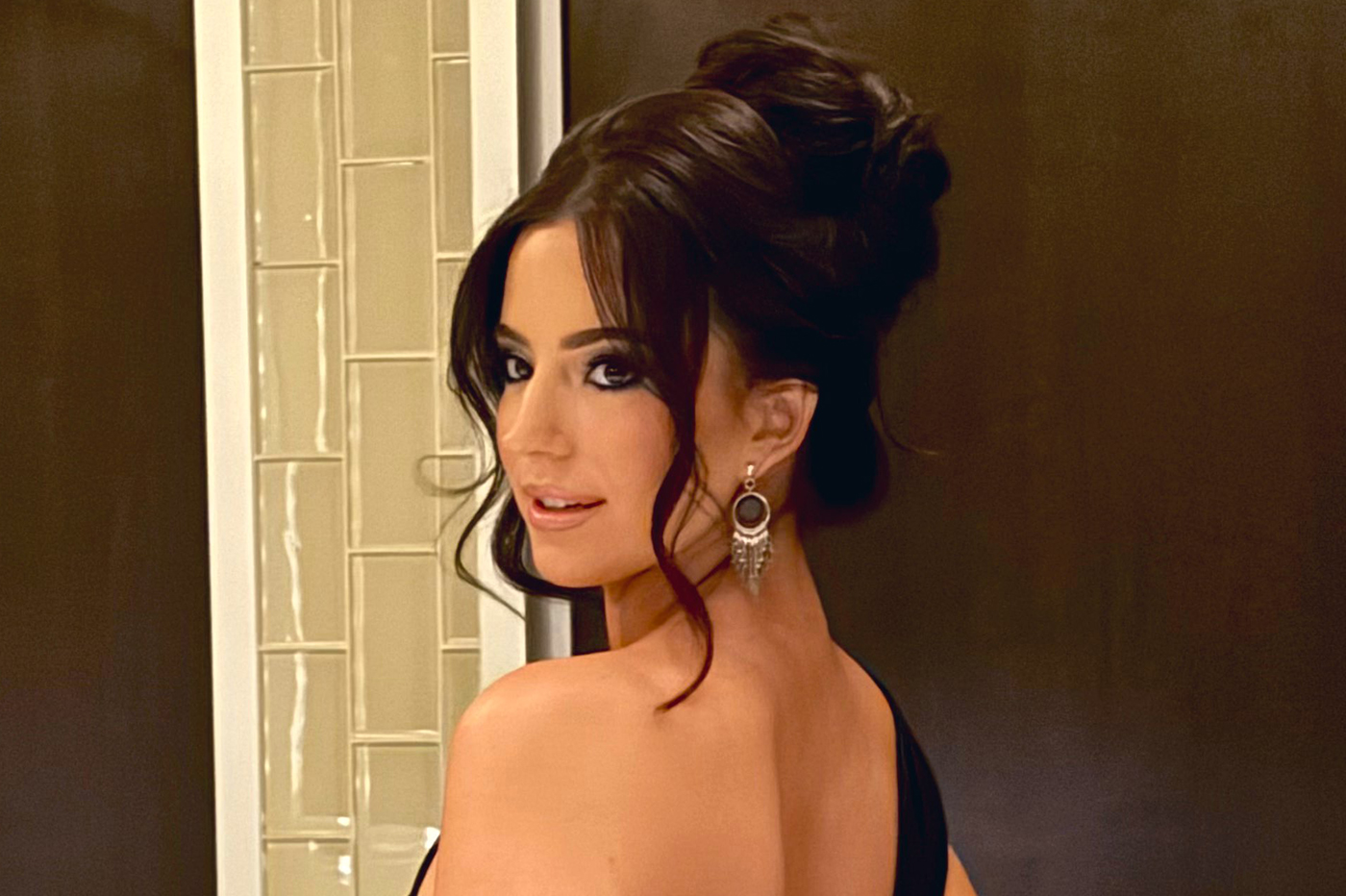

Our daughter Clementine, five, has just decided what she wants to be when she grows up. ‘A cleaner…and a mother,’ she says, in that order. Her mother, my wife Taffeta, winces at Clemmie’s ambition. Middle-class rules dictate that we should try to knock such traditional notions out of little girls’ brains. It’s not feminist and therefore bad.

But why? If this health crisis has taught us anything, it is that cleaning is one of the most important things human beings can do. And even in our horridly secular age, we all know deep down that motherhood is sacred. We need mothers now more than ever.

It’s odd. We’ve suddenly realized how ‘key’ so many workers are: doctors, nurses, teachers, food suppliers, plumbers, train drivers, the police, and so on. I may cringe at this Soviet social media fad of clapping the National Health Service, but I see that it lifts some spirits, and that might be useful in a pandemic. But I think the crisis should also remind us that the most key workers of all are parents — and mothers especially.

Clemmie has connected cleaning and mothering in her mind. That’s because, since our family has been locked in together in quarantine, she has seen her mother scrubbing away, endlessly tidying, giving orders and generally making sure that everything runs smoothly — while I sit about staring at screens failing to work from home.

Taffeta has, unlike me, risen magnificently to the challenge posed by the coronavirus. She never wanted to be a teacher — but as of this week, from Monday to Friday, she runs a homeschool for our three children in the kitchen. Every morning, the nine o’clock bell goes off on Taffeta’s phone, and she starts instructing the boys, while Clemmie and I pretend to do a Joe Wicks workout together in the sitting room. Then Clemmie joins the kitchen-school and I go upstairs to my ‘office‘ (a bedroom) and work. I come down for lunch, which Taffeta cooks, then I disappear again for most the afternoon while Taffeta organizes online art classes, music rehearsals, activities in the garden and social video calls so that the children can keep up with their friends.

When the boys hurt themselves, or each other, or the cat scratches Clemmie’s face, Taffeta transforms from teacher into nurse and makes them better. It all takes a titanic effort on her part. It is stressful. But she just never stops trying. It’s incredible to watch — whenever I look up from my phone, that is… It makes me think of my mother, who always did everything for me, and how bloody ungrateful I was. Motherhood is saintly.

Across the planet, millions of other households are doing what we are doing, and millions of mothers are sacrificing everything for their families. Women everywhere have been plunged into the domestic deep-end and are having to work much harder just to things afloat. The matriarchy has had to get to work, as it always does in major catastrophes.

If I’m gender-stereotyping here, there is a reason. Like lots of 21st-century fathers, I try to help but I usually fail. Often I’m better off just getting out the way. I’m not as good with the children as Taffeta is, not as patient or loving or kind. My cooking is bad. I realize I am lucky to have such a wife — or perhaps Taffeta is unlucky to have such a husband — but it also occurs to me that, if families are the building blocks of society, motherhood is what bakes the bricks.

Last weekend was Mothering Sunday in Britain, but in this crisis, perhaps we should applaud mothers every day. I hope Clemmie will be grow up to be one, too, once she’s finished the washing up. I must get off my phone.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.