In May of last year, at the Saturday corrida of the Feria de Pentecôte in Nîmes – “no hay billetes” – I had the traveler’s luck to find myself seated next to the son of one of the late, great French toreros of the 1970s. We were seated high in the Arènes de Nîmes, the city’s Roman amphitheater completed around 100 years after the Crucifixion – a structure far superior in function and beauty to Rome’s defunct and messily eviscerated Colosseum. In Nîmes, as in neighboring Arles, the French have triumphed over the Fall of Rome in restoring these structures to something of their original purpose: hosting feats of gladiatorial courage tamed by a strict protocol. But that inheritance has once more been threatened by legislation that contests its place in the Fifth Republic.

As the low Occitan sun lowered further still, between the tercios – the “thirds” that constitute the liturgical structure of the corrida – I confessed my insecurities to my new friend. How, as an Englishman (Protestant no less) at his first bullfight in France, could I dare to pass comment on this sacred art? “But it is perfect,” came the response, “these are the same insecurities that plagued the first toreros of France.” My friend’s consolation had its point: French bullfighting, or rather Spanish toreo in France, has always been predicated on degrees of insecurity and instability since Napoleon III held a grande corrida at Bayonne in 1853 to honor his new Andalusian wife, Empress Eugénie. It was a 19th-century import only formally legalized a century later but spawned of a tradition dating to the 1280s. Even after tauromachie was legislated in 1951, Spanish breeders swore never to send Spanish bulls to France. But in its unlegislated form, tauromachie (the broader, Gallicized term for the world of bullfighting) prospered across France: the Roman structures of the south were restored and major bullrings erected in Béziers and Bois de Boulogne, Paris – an albeit momentary suspension of Parisian bourgeois sensibilities. The 150 or so bullrings of the south today – legally registered as slaughterhouses – are a testament to l’espirit du sud, the spirit of the south. “La tauromachie en France… c’est comme une aventure,” my tutor confirms.

But the great adventure was, at one point, close to expiry. In November 2022, a bill for its ban was brought to the National Assembly by the left-wing La France Insoumise (LFI), led by its deputy, Aymeric Caron, an “ecosocialist” pioneer. Since 2011, bullfighting has been exempt from French animal-welfare penal law, classified as French Intangible Cultural Heritage in places where it is an “uninterrupted local tradition.” This is a technicality that Caron and supporters of La Societé protectrice des animaux (SPA) argue is a misclassification – corrida being a Spanish import. In several cases, the SPA has attempted to prevent minors from attending corridas and bullfighting schools – a supreme level of puritanism that effectively certifies bullfighting’s eventual end. La Monumental, Barcelona’s striking Byzantine-revival arena, stands as a vacant reminder across the border of the last corrida in Catalonia, held in September 2011. But cross-party conservative parliamentarians successfully stalled the LFI’s bill. Caron renewed his legal attempts on the eve of the Arles feria in April this year with a bill titled (in translation), “One small step for the animal, one giant leap for humanity.” But even according to the president of the Alliance Anticorrida, Claire Starozinski, this too is doomed to fail.

The threat to bullfighting in France has, in turn, created a reaction. In November 2022, 13 French toreros appeared with their pink-and-yellow capes under the Eiffel Tower in silent protest of the LFI’s first bill. It was the sort of image, dignified and charged with its own kind of cutting irony, that political activists seldom achieve. Of the 2 million annual spectators of French bullfighting, according to the Observatoire national des cultures taurines, support is now most spurred by the youth whose loyalties are clearly represented all over the French bullrings in banners that read, #OUIÁLACORRIDA – yes to bullfighting. One name has dominated the French defense of bullfighting: Simón Casas, a retired Nîmois bullfighter turned businessman, now-visionary patron of the arenas in Nîmes, Arles and Valence, first French impresario of Las Ventas in Madrid and dubbed chef d’État de la tauromachie – the head of the bullfighting state – because of it. At the mention of his name, my guide smiles: “we have a photograph of him jumping the barriers as an espontané in the 60s…” An espontané is a wild spectator who jumps the barrier to fight the bull himself.

For decades, the end of bullfighting has been proclaimed by those who detest it – and those love it. An aficionado at a nearby taurine meeting the following week, declaiming the decadence of bullfighting today, affirmed to me that “corrida – c’est fini!” (bullfighting is finished). I vainly protested in broken French and then we laughed and in thick Provençal toasted bulls with strong wine: we still drink from the same cup. We watched Sebastiàn Castella – dubbed at age 23 the “French savior of bullfighting” by a 2006 Wall Street Journal article – and we watched on as the white-capped peons, wielding their wide brushes, restored the sand and white lines so gracefully marked by Castella. Then followed Andrés Roca Rey, the Peruvian maestro who ranked world número uno in 2023. Castella’s baton has since been passed to a 25-year-old native of Nîmes, Raphael Raucoule – El Rafi – who, perhaps uncharacteristically for a torero, appears frequently in interviews in which he politely devastates his opponents, logically dismantling their outrage. His arrival on the sand to the tune of Bizet confirmed the return of the native.

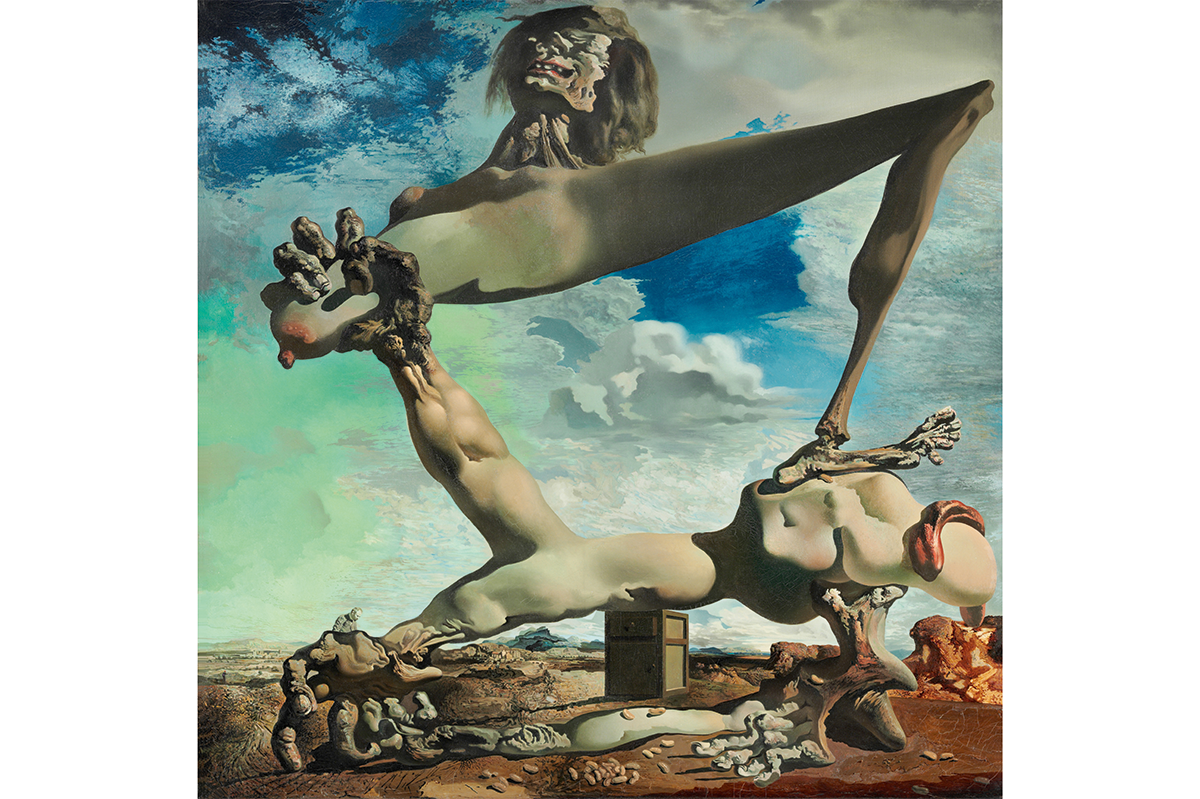

The European secular experiment, doomed to failure though it may be, drags with it the customs, traditions and culture of the European people. Thousands are dependent on bull-breeding as the bull is dependent on them – as custodians of ancient bloodlines descended from prehistoric Aurochs, and guardians of the vast territory over which the beasts nobly roam. A ban automatically implies the extinction of this ecology. Corrida, at least in France, is what has been termed an insolent vestige or inverted mirror of an era, with its hierarchy of competence (that which any great art form immediately implies), the spontaneous, living mythology into which both performer and audience play a part, the depth and complexity one finds in a spiritual doctrine. It sits uncomfortably in the French national discourse – a reminder that state and politician make themselves welcome where they are not. The spectators do not merely applaud courage; in perhaps the last instance of authentic celebrity left in the modern world, they see the triumph of man and the glory of death. “There is a mystery to corrida in France,” my friend confirms: first imported by mingling Catalan and Occitan bloodlines, celebrated by the last Emperor the French have known as their own, shunned by Spain until, as Ernest Hemingway put it, the fighter El Cordobés “conquered the Pyrenees” – then celebrated in situ by the art’s most famous Spanish advocate, Picasso. And after the arena is emptied and the dust is stilled by lengthening shadows, Roman cobbles are washed of a city and its briefly shown revelations of an ancient code that tells us heroism is not dead.

Leave a Reply