On the day I arrive in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital, it’s almost impossible to see the mountains that loom behind the city because of the smog. By the late morning, they have started to appear. Second-hand cars from around the world jam the four-lane highways that make up the city’s post-Soviet grid. Left-hand-drive cars (the correct side for Kyrgyz roads) are prized. My driver is on the right. He swerves to avoid a container truck covered with Chinese symbols.

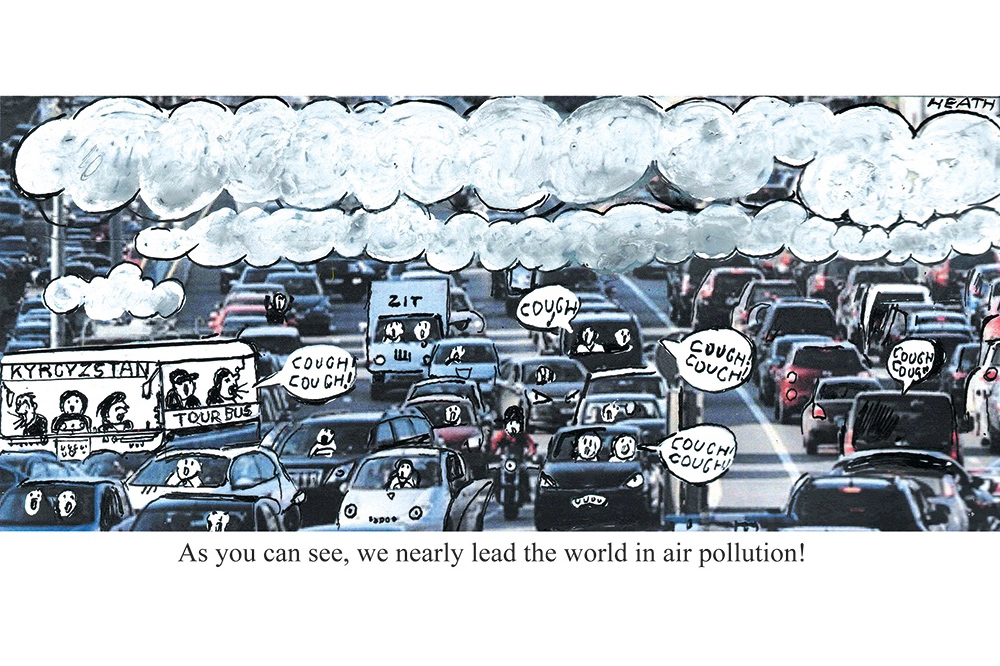

“If you’re walking, you’re poor. The car is like the new horse,” explains Anton Usov, chief spokesman for central Asia at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. In Bishkek’s art gallery, a photographic exhibition highlights the city’s smog problem: Bishkek is ranked the second most polluted city in the world by the United Nations Environment Program. Most of the problem is down to the heavy use of coal for central heating in winter and air conditioning in summer. That the price of gasoline has dropped since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine doesn’t hurt either.

Kyrgyz pride themselves on being, outwardly at least, the most democratic of the “Stan” countries: Kyrgyzstan holds parliamentary elections, although in 2020 and 2021, the votes resulted in mass protests and accusations of rigging. Aisha Mambetalieva, a Bishkek native, explains that the country has swung almost too fast from nomadic life to Soviet rule, then independence and capitalism. She sums it up by explaining the changes made to the Kyrgyz language, which until the twentieth century was written in Arabic. Latin script was adopted in 1928 until Stalin mandated the Cyrillic alphabet be used. Today, Latin script is slowly creeping back. “We need time to get used to the changes,” she says.

Down the road from Bishkek, in Tokmok, a former US military training base is used by the Kyrgyz military. Until 2014, Kyrgyzstan was the only country in the world to host both US and Russian military sites. The American presence feels a distant memory. Instead, Kyrgyzstan now treads a delicate position. In May, President Sadyr Japarov joined Vladimir Putin at Russia’s Victory Day parade in Moscow shortly after announcing deeper military co-operation. “The heads of state emphasized the importance of strengthening the Kyrgyz Republic’s armed forces and developing Russian military facilities on its territory,” the Kremlin said.

Lake Issyk-Kul is Kyrgyzstan’s biggest body of water and home to a Russian base. On its shores sits a decrepit property. The walls are muralled with fading scenes of camels, donkeys and half-finished mud yurts. The iron gates have all rusted. A crumbling Buddha sits nearby. This gaudy Ozymandias once belonged to Maxim Bakiyev, the son of the former Kyrgyz president. But since the whole family fled the country during the so-called “Melon Revolution” of 2010, it has been left to crumble.

By contrast, construction is under way on the road which passes by the property, a joint venture between China and Arek Road, a Kyrgyz construction company. “You need Chinese workers to get the job done,” our guide Ormon jokes. The road will connect Kyrgyzstan with its much larger neighbor. The relationship was cemented at the second China-Central Asia summit in May, an event conveniently timed to clash with the G7 summit in Japan.

Small, white, identikit mosques are scattered through the lake’s villages. More than a quarter of Kyrgyzstan’s mosques have been built since the USSR fell, many with Saudi backing. “Mosque diplomacy” is the term we hear used. Rush, a local shepherd, says he has noticed the influence of a more fundamental style of Islam. Young men are growing longer beards. He fears for the nomadic way of life in a nation where some of the last roving communities exist. “We say we are Muslim but we are nomads. We just need the weather, the mountain,” he says, as we sip on light black tea in his home below the foothills of the Ala-Too range.

Back in Bishkek, the rifts between young and old are broadening. The young, a generation that never knew Soviet rule, have their eyes fixed on opportunities in Europe, if they can manage to get a visa, that is. It’s no easy process, says Valerhy, the son of a local shopkeeper. His English is impeccable, more precise than most native speakers, but his first attempt to reach the UK was refused. Instead, he will try the Netherlands where he already has friends. Our conversation is conducted at just above a whisper so that Valerhy’s pro-Russian father cannot hear about his plans from the next-door room.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.