In recent columns, we have visited some lesser known spots in Burgundy – Saint-Romain, Maranges, Ladoix – where the wines are good and the prices reassuring. This time, I’d like to travel to Champagne to introduce you to one of my most exciting recent discoveries, the wines of Egly-Ouriet. You know about Dom Pérignon, Krug, Bollinger and Taittinger. They can be very good. Egly-Ouriet is something else.

Remember that Champagne occupies the northernmost precinct of French wine production. The northeastern bit of the area borders Belgium. It’s chilly up there, and damp. Nietzsche famously declared that, “What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.” That may not be true of people. I am pretty sure it is not. But the observation has a certain application to wine. Difficult conditions make the grapes try harder.

This is something that Champagne makers understand instinctively. It is said the Egly family and its ancestors have been growing grapes in and around the eastern valley of Montagne de Reims since the 18th century. The vineyards around Ambonnay, Bouzy and Verzenay are their epicenter. At first, Egly-Ouriet sold most of its fruit to other winemakers. But in the mid-20th century, the family began marketing its own wine. After Francis Egly took over the business in the 1980s, the winery developed a cult following. Today, it makes some of the most complex and sumptuous Champagne in the world.

A word one often sees in connection with Egly-Ouriet is “precise.” In some ways that is curious, because Egly’s approach to winemaking can also be described as laissez-faire or “minimalist.” His spots of dirt offer some of the choicest grand cru and premier cru terroir in Champagne. Some of his grand cru vines in Ambonnay date from 1946. Planted on shallow chalk soils with only about a foot of topsoil, they make, in Egly’s hands, some remarkable wines.

Egly takes great pains to let nature do the talking. He uses local yeasts and minimal pressing. He listens hard to the weather, the “unheard melodies” of the land that he is blessed to cultivate. Galileo said that wine is sunlight caught in water. Francis Egly makes the sunlight sparkle. Time equals money. One reason Champagne is expensive is that it requires a lot of time to make. By law, nonvintage Champagne must age for a minimum of 15 months, vintage for 36 months. Some of Egly-Ouriet’s offerings age for 60 months, some of its grand crus age for 84 months, a few for an astonishing 96 months, eight years, in the barrel and sur-lattes. Look for the initials “V.P.,” which stands for “vieillissement prolongé,” or “prolonged aging.”

So what does all this time and cultivation cost? Some of Egly-Ouriet’s Champagnes are expensive. Vintage Grand Cru Brut Millesime and Extra-Brut Blanc de Noirs Les Crayères are dear. Bring along five or six Benjamins for a recent vintage, more for older ones. But some of its wines are, as these things go, veritable bargains. Its premier cru Brut Les Vigne de Bisseuil, for example, can be yours for about $100. Its Les Prémices is about $70. They are all delicious, with that bread-like yeastiness and blooming, succulent mouthfeel that most of the best Champagnes feature.

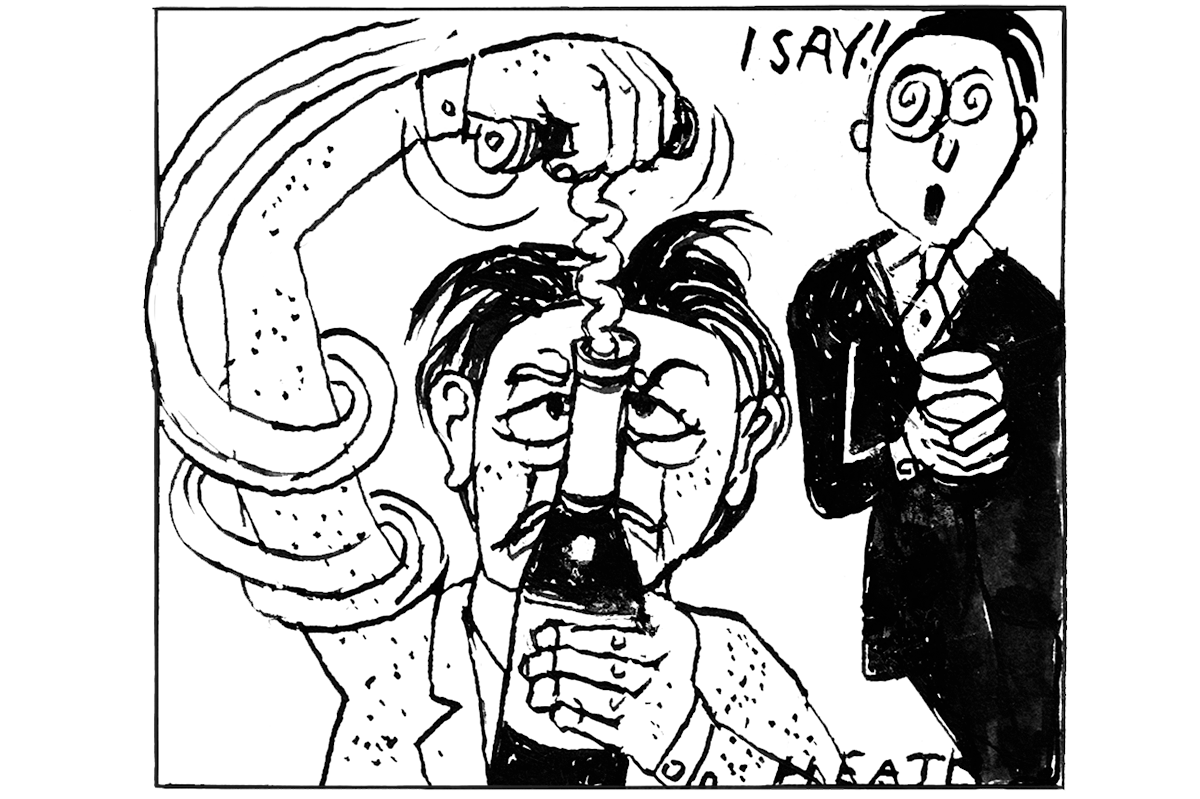

I have had several bottles of Champagne from Egly-Ouriet in the last few years. After a gala event in Washington at the end of last month, I repaired with some friends to Butterworth’s, DC’s trendy and most politically mature refectory (at 319 Pennsylvania Avenue SE) with a bottle of the Rosé Grand Cru Extra Brut. The cuvée was from vineyards in Ambonnay, Bouzy and Verzenay – 70 percent pinot noir, 30 percent chardonnay, tinctured with 5 percent still red wine from Ambonnay. It was nonvintage, but on a base of 2019 grapes, disgorged in October 2024; the wine had lingered 48 months on the lees.

We were in a mood to be appreciative, but even with an appropriate discount for what (in another context) Alan Greenspan called “irrational exuberance,” we all agreed that the wine was spectacular. It started with an intense nose, redolent of a pâtisserie, proceeded with a kaleidoscope of shifting tones and flavors and adumbrations, and finished long, with that bright intensity that all good Champagne deploys. This wine is not cheap, but neither is it exorbitant. A bottle can be yours for about $200.

I will end by noting the Egly-Ouriet also makes an excellent still pinot noir called Coteaux Champenois Rouge. It comes from vines that are 60 years old or older in a single south-facing vineyard in Ambonnay directly below the Les Crayères chalk pit. We followed the Champagne with a bottle of the 2022. It was unlike any Burgundy pinot noir I have had. Intense yet balanced, full-fruited yet reticent, severe yet coaxable. Bottled by hand directly from the barrel, it is a wine that had a pampered yet strenuous upbringing. It is usually about $300 a bottle. Definitely vaut le voyage, as Baedeker would say.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply