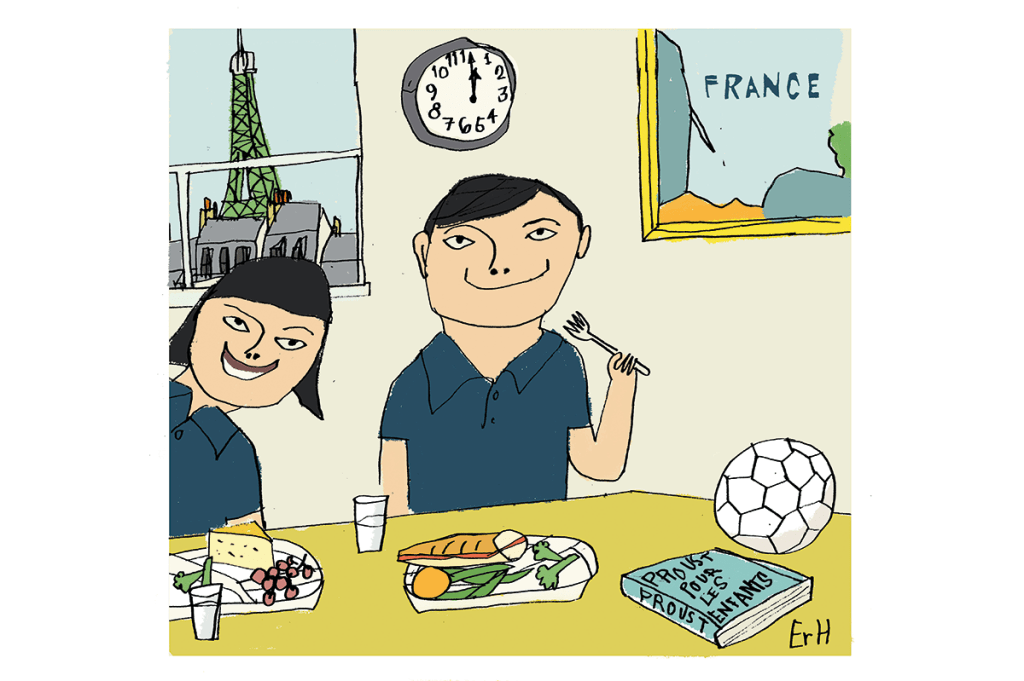

Since moving to France, one of my greatest pleasures has been rushing to pick up my two grandchildren from the tiny schoolhouse in the village of Monthelie. I can’t wait to hear about what they had for le déjeuner.

Le déjeuner scolaire, a three- to four-course lunch, subsidized by the government, is sacrosanct. The French even have a phrase for socializing and eating together: la commensalité. They know that “a family that eats together, stays together.” I remember when America, where I used to live, understood that, too.

Rarely do you see the French eating lunch or dinner alone in restaurants, bistros or cafés. The exception is for une pause café or morning coffee, when the French do prefer to be alone with a croissant, newspaper and quite possibly a cigarette.

Organic or “bio” food, free from pesticides and locally grown, has become essential to le déjeuner scolaire. There are even specific cooking schools to teach future chefs what and how to cook for French cantines scolaires. Cantineurs oversee the lunch hour and help the youngest pupils to cut up their cordon bleu.

Here in La Côte d’Or, parents pay between one and five euros per child for lunch, according to their means. The gourmet meal is subsidized by the region, as well as by the central government in Paris. Six million French children are not only well-educated and well-fed but taught to understand gastronomy.

The culinary education begins in primary school and continues through high school (when children take the very demanding baccalauréat). French schoolchildren are given a starter, main, vegetables, fruit, bread, cheese, water and a dessert. Menus are posted online, usually a week or two in advance, with suggestions for the evening meal. The focus is always on the nutritional balance deemed essential for children.

This form of French school lunch has existed since the end of World War Two. The Fifth Republic also said children should be given at least 30 minutes to eat their meal, because it should take time. It should then be followed by at least an hour of play before lessons restart.

One might wonder whether French children’s apparent intelligence and cultural sophistication stems, at least in part, from their obligatory déjeuner and early exposure to such a rich culinary tradition. In France, shaping young food enthusiasts in the school cantine is just as important as teaching the nuances between a standard past tense and le passé simple. Children are encouraged to spend enjoyable moments together, so as to learn savoir-vivre.

Which all explains why, if you ask a French schoolboy to name his favorite cheese, he will rattle off at least six and have to stop and think about which is really his favorite. The taste for French cheese starts the moment a toddler is hungry.

Any American who has moved to France will be astonished at how much time the French can take to eat a meal (other than breakfast). Even children’s birthday parties take hours, on account of the endless, obligatory apéro for the parents. Celebrating a child’s birthday in France is time-consuming and almost as expensive as throwing a dinner party.

Recently, my grandson confessed to me that the reason he chose his new collège (middle school) out of the two in Beaune was for its déjeuner, which is renowned locally. On Fridays, he is given a choice of desserts. He is rhapsodic about the stracciatella (a version of tiramisu, with French ricotta and raspberries). So French children aren’t totally different from their counterparts in other countries: they love their sweets, at least on Fridays. But they will want some cheese, too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply