The other week my eldest daughter and I were staying with friends in Richmond for the launch of Jeremy’s third collection of Low Life columns. The night before the anniversary of his death — the day of the launch — I woke at 2 am and unable to sleep was back in the cave holding Jeremy’s hand; machines clicking and beeping as his life ebbed unpeacefully away. He died at 9 am.

A few weeks after Jeremy died, I dreamt he walked into the house… he looked fit, strong and full of life

At 9:05 am, in tears and still wearing a nightie, jumper and flip-flops, I ran downstairs, almost colliding with one of our hosts, out the back door to the bottom of the garden. Beyond the high wooden fence and gate a path ran parallel with the Thames. I reached up to open the latch. The Thames is quiet there; a great oily mass drifting towards Southend-on-Sea, where Jeremy was born. I stood on the path watching it until in the distance a man came jogging towards me.

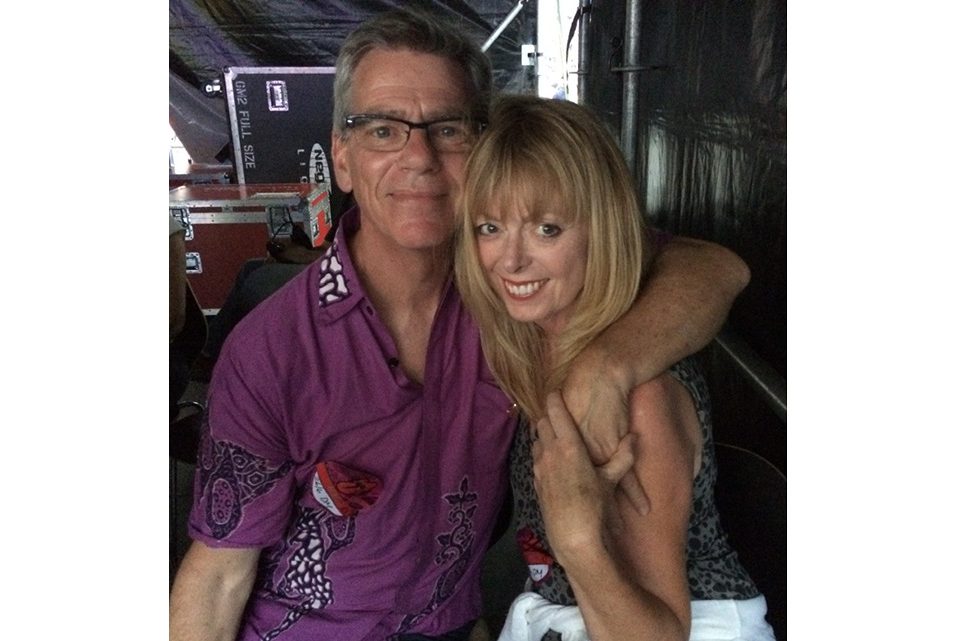

The book launch passed in a blur. I hardly spoke to anyone. Because I’d had so little sleep, a few drinks and was anxious, the people I did talk to would’ve been justified in doubting my sanity or thinking I was on drugs. But I did just about manage to hold it together adequately and speak to the company as a whole. I told them this: a few weeks after Jeremy died, I dreamt he walked into the house. He looked fit, strong and full of life. I was overjoyed and said: “How did you get here?” He just grinned in that cheeky way he did and said: “What day is it Treen?” “It’s Monday…’ (column deadline day) “Oh fuck! What am I gonna write about?” “Darling, you died three weeks ago — and here you are — back. At least one column. We’re all desperate to know.” I’d like to say we embraced, but a dream will only take us so far.

After the thrill of London I spent ten days between Oxfordshire and Glasgow with my three daughters and two granddaughters. Towards the end of the second week I took a break from belly-crawling across the living room floor with the eldest toddler, pretending to be crocodiles sneaking up on mommy, to have a night away with school friends.

We’ve known each other since first year at high school — forty-eight years. Alyson is so beautiful she’s rarely had to work but she’s suffered ill health on and off for most of her life. Two years ago we thought we were losing her when she reacted badly to a stem cell transplant. This was around the time my middle daughter had a delayed (because of Covid) diagnosis of thyroid cancer and Jeremy’s prostate cancer became terminal. We chose a night at nearby Mar Hall on the banks of the Clyde at Erskine. Alyson has been unable to travel much further.

Built in the 1840s for Lord Blantyre, in 1916 the manor house became the Erskine Hospital for Limbless Sailors and Soldiers. I’d been there before. Around 1966 my father, a pituitary giant, who was 7ft 4½in tall, lost the use of his legs and became mostly confined to a wheelchair. My mother went out to work and my dad, by then in his early fifties, looked after me while I, aged three, became his legs. Supervised by Bess, our elderly white boxer dog, I’d climb up on to the kitchen cupboards to boil a kettle and make dad cups of sugary Nescafé or run errands around the farmhouse. There were no carers. I remember helping him lift his great crippled legs and feet into a basin. Flakes of skin and soap scum floating in tepid water.

One of the old soldiers from Erskine Hospital made my father’s shoes. Despite being disabled and almost blind, dad still drove his adapted Armstrong Siddeley with me bouncing around untethered on the front seat beside him. My nerve-wracking job was to look out for traffic and shout “all clear” at the main T-junction into the village. The only time I can remember him shouting at me was once when I got it wrong.

The Elizabethan revival entrance hall to the manor was the recreation room. Men with missing legs or only half a face stopped their chess, cribbage or snooker to stare at us through the fug of 1960s cigarette smoke. I could hardly bear to look up. Dad with his great height and acromegaly (lengthened jaw and exaggerated cheekbones), and me, a small, unattractive, pale, ginger girl with an enormous head that sat on tiny shoulders like a television, were an odd sight too.

Fifty-six years later, three of us walked into the same hall. The sadness of the place has all but gone but there’s still something. A lingering fetch perhaps. Over a glass of champagne and later dinner, we covered the usual ground: teachers, ex-boyfriends, husbands, work, sex, books, children, bereavement and politics. We argued comically with Daniel, the restaurant manager, about the lack of a reasonably priced white Burgundy. “Pouilly-Fumé isn’t Burgundy.” “Aye, but it’s a dry white wine.” “We know but we don’t like Sauvignon.” Turned out Daniel was right and we enjoyed the wine. The food was good enough and the rooms comfortable. After ten hours of talking and laughing, Alyson, like me a social smoker, was for the first time since her transplant feeling sufficiently well to ask if I had any cigarettes. Joy.

Low Life: The Final Years by Jeremy Clarke is out now. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply